Ex cathedra

by Joaquim Maria Machado de Assis“Godfather, you’ll go blind from that, sir.”

“What?”

“You’re going to go blind. Reading is so sad. No sir, give me that book.”

Caetaninha took the book out of his hands. Her godfather paced around and then went into his study, where there was no lack of books. He closed the door behind him and kept reading. That was his vice. He read excessively; he read morning, noon, and night, during lunch and dinner, before going to sleep, after bathing; he read as he walked, read standing up, read in his house and in his barn; he read before reading and he read after reading; he read all sorts of books, but especially books on law (in which he’d received his degree), mathematics, and philosophy. Lately, he’d also been reading up on the natural sciences.

Worse than going blind, he went crazy. It was near the end of 1873, in Tijuca, when he started to show signs of mental disturbance; but, since the episodes were minor and few, his goddaughter only started to notice the difference in March or April of 1874. One day, over lunch, he interrupted his reading to ask her:

“What’s my name again?”

“What’s your name, godfather?” she repeated, astonished. “Your name is Fulgencio.”

“From this day forth, my name will be Fulgencius.”

Fulgencio lived for the written word, the printed word, doctrines, abstract thought, principles, and formulas. He eventually passed from mere superstition to true hallucination of the theoretical.”

And, burying his face in the book, he went on reading. Caetaninha mentioned the episode to the slave women, who admitted that they’d had their doubts about him for some time, that he hadn’t seemed well. Just imagine how fearful she was; but her fear soon passed, leaving only compassion behind, which increased her affection for him. His mania was also limited and docile, and was only related to books. Fulgencio lived for the written word, the printed word, doctrines, abstract thought, principles, and formulas. He eventually passed from mere superstition to true hallucination of the theoretical. One of his maxims was that liberty would not die, so long as there was a single piece of paper on which to declare it. So one day, waking up with the idea of improving the condition of the Turks, he wrote a constitution for them and sent it to the British diplomat in Petrópolis as a gift. On another occasion, he set about studying the eyes in anatomy books to verify whether they were really able to see, and concluded that they were.

Tell me, readers, whether, under such conditions, Caetaninha’s life could have been a happy one? It’s true that she wanted for nothing, because her godfather was rich. He had been the one who’d raised her, from the age of seven, when he lost his wife. He had taught her to read and write, French, and a little bit – so as not to say almost nothing – of history and geography, and had charged the domestic slaves with teaching her embroidery, lace-making, and sewing. There’s no denying any of that. But Caetaninha had turned fourteen and, if, in the early years, her toys and the slaves were enough to entertain her, she was now at an age when toys go out of style and slaves hold no interest, when no amount of reading or writing can transform a solitary house in Tijuca into a paradise. She went out sometimes, but rarely, and always in a rush. She never went to the theater or to dances, never made or received visits. Whenever she saw a cavalcade of men and women on horseback out in the street, her soul would ride pillion on one of the horses and ride off with them, leaving only her body behind, right next to her godfather, who kept on reading.

One day, while she was out by the barn, she saw a young man mounted on a little mule approach the gate, and heard him ask her if this was the house of Doctor Fulgencio.

“Yes, sir, this is.”

“May I speak with him?”

Caetaninha replied that she would see about it. She walked into the house and went to the study, where she found her godfather contemplating, with the most delighted, beatific expression on his face, a chapter of Hegel.

“A young man? What young man?”

Caetaninha told him that the young man was in mourning clothes.

“Mourning clothes?” repeated the old doctor of law, hastily closing his book. “It must be him.”

I forgot to mention (although there’s time enough for everything here) that three months earlier, Fulgencio’s brother had passed away up north, leaving behind a son. A few days before he died, the brother wrote him, entrusting him with the orphan he would soon leave alone, and Fulgencio replied that he should come down to Rio de Janeiro. When he heard that there was a young man in mourner’s garb at his gate, he assumed that it must be his nephew, and he was right to do so. It was the nephew indeed.

It seems that, up to this point, there has been nothing in this story that departs in any way from a naively romantic tale: we have an old lunatic, a lonely, sighing maiden, and we’ve just seen a nephew suddenly arrive on the scene. So that we don’t come down from the poetic region in which we currently find ourselves, let me merely mention that the mule on which Raimundo arrived was led to the stables by one of the blacks; I’ll also gloss over the circumstances pertaining to the young man’s accommodations, limiting myself to mentioning that, since his uncle had completely forgotten that he’d told him to come – by dint of spending all his waking hours reading – nothing was ready for him at the house. But it was a big, affluent house, and, an hour later, the young man was set up in a gorgeous bedroom, from which he could see the barn, the old well, the wash basins, plenty of green leaves, and the vast blue sky.

The idea of getting them to marry somehow fused together with one of his recent opinions that love was conducted in empirical fashion and lacked a scientific basis.”

I believe I haven’t yet mentioned the young guest’s age. He has fifteen years under his belt and a hint of fluff on his upper lip; he’s nearly a child. Now, if this made our dear Caetaninha restless, and if the slave women went from one end of the house to the other eavesdropping and talking about “ole massa’s nephew from out of town,” it was only because there was nothing else going on in their lives there, not because he was a dashing, grown man. The man of the house had this same impression, but there’s a difference here. The goddaughter didn’t realize that the purpose of upper-lip fluff is to one day become a mustache, or if she did think about this, she only did so in passing, and it’s not worth writing it down here. Not so with old Fulgencio. He understood that he had before him the makings of a husband, and he resolved to get them to marry. But he also saw that, short of taking them by the hand and ordering them to love each other, chance and circumstance could lead these things down a different path.

One idea begets another. The idea of getting them to marry each other somehow fused together with one of his recent opinions. It went like this: in matters of the heart, calamities or simple displeasures stemmed from the fact that love was conducted in empirical fashion and lacked a scientific basis. A man and a woman who understood the physical and metaphysical reasons for this feeling would be more apt to receive it and nurture it effectively than another man and woman who knew nothing of the phenomenon.

“My little ones are yet green,” he said to himself, “I have three or four years ahead of me, and I can start preparing them now. We’ll proceed logically: first the foundations, then the walls, then the ceiling… instead of starting with the ceiling straight away… A day will come when people learn to love the way they learn to read… And on that day…”

He was stunned, dazzled, delirious. He went over to the bookshelves, pulled down a few volumes – astronomy, geology, physiology, anatomy, jurisprudence, political science, linguistics – and opened them, leafed through them, compared them, copying down a little from this one and little from that one, until he had a program of study. It was composed of twenty chapters, in which he put forth general concepts about the universe, a definition of life, a demonstration of the existence of man and woman, the organization of societies, the definition and analysis of the passions, a definition and analysis of love, as well as its causes, necessities, and effects. To tell the truth, the subjects were daunting, but he intended to make them more amenable, discussing them with simple, common language, giving them a purely familiar tone, like Fontenelle’s astronomy. And he stated emphatically that the essential part of the fruit was the pulp, not the peel.

All of this was ingenious, but here’s the most ingenious part: he didn’t invite them to learn. One night, gazing up at the sky, he said that the stars were shining brightly. And what were stars, after all? Did they, perchance, know what stars really were?

“No, sir.”

It was only a small step from this point to the beginning of a description of the universe. Fulgencio took this step so nimbly and naturally that they were enchanted, and asked for the entire journey.

“No,” said the old man, “let’s not exhaust it all today. This can’t be understood well if it isn’t learned slowly. Maybe tomorrow or the day after…”

There’s such a tiny difference between fourteen and fifteen year-olds, that all they have to do to bridge the gap is hold out their hands to each other. And that is what happened.”

In this shrewd manner, he began to execute his plan. The two students, astonished by the world of astronomy, asked him to continue his lessons day after day, and although Caetaninha was a little confused at the end of this first chapter, she still wanted to hear all the other things her godfather had promised to explain.

I’ll say nothing of the familiarity between the two students, since it should be obvious. There’s such a tiny difference between fourteen and fifteen year-olds, that all they have to do to bridge the gap is hold out their hands to each other. And that is what happened.

At the end of three weeks, it seemed as if they’d been brought up together. This alone was enough to change Caetaninha’s life dramatically, but Raimundo gave her even more. Not ten minutes ago we saw her watch longingly as a cavalcade of men and women passed by in the street. Raimundo quenched this longing, teaching her to ride despite the reluctance of the old man, who was afraid some disaster would befall her. He eventually agreed and readied two horses for them. Caetaninha ordered a custom-tailored riding outfit, and Raimundo went into town to buy her gloves and a whip – with his uncle’s money, of course, which also provided him with boots and the rest of the men’s riding gear he needed. It was soon a pleasure to see the two of them, graceful and daring, riding up and down the mountainside.

At home, they were always together, playing checkers and cards, tending to the birds and plants. They argued a lot, but according to the slave women, they were play-fights, which they only got into so they could make up later. And that was the extent of their quarreling. Raimundo would go into town sometimes at his uncle’s request, and Caetaninha would wait at the gate for him, anxiously scanning the horizon. When he arrived they’d always argue, because she’d want to take in the heaviest packages, saying that he must be tired, and he would try to give her the lightest ones, claiming that she was too dainty.

At the end of four months, life in the house had changed completely. You could even say that only then did Caetaninha start to wear flowers in her hair. Previously, she would often show up at the lunch-table with her hair uncombed. Now, not only did she comb her hair first thing in the morning, but she even, as I mentioned, wore a flower or two in her hair. The flowers were gathered either the night before – by her – and put in water, or the next morning – by him – and he would take them to her window. The window was high off the ground, but Raimundo was still able, by standing on his tiptoes and extending his arm, to hand the flowers to her. It was around this time that he developed the habit of teasing out the fluff on his upper lip, tugging it to one side and the other. Caetaninha even started to slap his hand away, to rid him of such a bad habit.

Meanwhile, the lessons continued regularly. They already had a general idea of the universe and a definition of life, which neither of them understood. Thus they entered the fifth month of instruction. In the sixth, the old man began to demonstrate the existence of man. Caetaninha couldn’t contain her laughter when her godfather, explaining the subject at hand, asked them if they knew that they existed, and why. But she quickly became serious again, and answered that she didn’t.

“You either?”

“No, me either, sir,” said the nephew in agreement.

While the old man spoke – impartially, logically, deliberately – the two students made thirty thousand efforts to listen to him; but there were also thirty thousand things to distract them.”

Fulgencio began his general, profoundly Cartesian demonstration of this fact. The following lesson took place in the barn. It had rained a lot in the previous days, but now the light from the sun flooded everywhere, and the barn looked like a beautiful widow who has traded her widow’s veil for that of a bride. Raimundo, as if wishing to imitate the sun (the great ones naturally copy each other), shot a wide, long look from his pupils, which Caetaninha received from him, quivering like the barn itself. Fusion, transfusion, diffusion, confusion, and profusion of beings and objects.

While the old man spoke – impartially, logically, deliberately, making extensive use of formulas, his eyes staring out at nothing in particular – the two students made thirty thousand efforts to listen to him; but there were also thirty thousand things to distract them. At first it was a pair of butterflies frolicking in the air. Would you please explain to me what’s so extraordinary about a couple of butterflies? I’ll concede that they were yellow ones, but this detail doesn’t serve to explain the distraction. The fact that they were chasing each other – now flitting to the right, now to the left, now down, now up – isn’t the reason for their sidetracked attention either, since butterflies never fly in a straight line, like columns of soldiers.

“The understanding,” said the old man, “the understanding, as I’ve already explained…”

Raimundo looked at Caetaninha, and found her looking over at him. Both one and the other seemed embarrassed and bashful. She was the first to lower her eyes to her feet. She then raised them in order to look somewhere else, somewhere farther off, at one of the walls of the barn. Since they passed by Raimundo’s eyes as they made their journey, she glanced at them and looked away as quickly as she could. Fortunately, the wall presented a spectacle that filled her with admiration: a couple of swallows (it was a day for couples, it seems) were flitting about it, with that grace peculiar to winged beings. They chirped as they cavorted, saying things to one another – who knows what they said, maybe this: that it was a very good thing that there was no philosophy on the walls of barns. Suddenly, one of them flew off – probably the lady – and the other – the gentleman, of course – wouldn’t let himself get left behind; he spread his wings and followed the same route. Caetaninha lowered her eyes to the straw on the ground.

When the lesson ended a few minutes later, she asked her godfather to keep going, and, since he declined, took his arm and invited him to take a stroll around the barn with her.

“It’s too sunny,” replied the old man.

“We’ll walk in the shade.”

“It’s too hot.”

Caetaninha proposed that they continue the lesson on the porch, but her godfather mysteriously told her that Rome wasn’t built in a day, and then stated that they would only continue the lesson two days later. Caetaninha retired to her room, where she remained for three-quarters of an hour with the door closed, sitting, standing by the window, pacing from one side to the other, looking high and low for things that she was already holding in her hands, and even going so far as to see herself on horseback, trotting up the street next to Raimundo. Suddenly, she thought she saw the young man out by the wall of the barn, but upon closer inspection she realized it was just a couple of beetles, buzzing about in the air. And one beetle said to the other:

“You are the flower of our species, the flower of the air, the flower of flowers, the sun and the moon of my life.”

To which the other replied:

“No one is your equal in beauty and grace, your buzzing is the echo of divine tongues. But leave me… leave me…”

“But why should I leave you, you, the soul of the thicket?”

“I have spoken, king of these pure breezes. Leave me.”

“Don’t say that, you jewel and charm of the forest. Everything above and around us implores you not to say that. Do you know the song of the blue mysteries?”

“Let’s go listen to it among the green leaves of the orange tree.”

“The leaves of the mango tree are more lovely.”

“You are more lovely than both.”

“And you, sun of my life?”

“Moon of my being, I am whatever you want me to be…”

This was what the two beetles were saying. She listened to them as she daydreamed. When the beetles flew off, she turned away from the window, noticed the time, and left her bedroom. Raimundo had gone into town, and she waited for him at the gate: ten, twenty, thirty, forty, fifty minutes. When he got back they said very little, spending time together and then going separate ways two or three times. The last time they were together, she had brought him out on the porch to show him a bauble that she had thought was lost, but had just found. Reader, show her the courtesy of believing that it was a complete fabrication. Meanwhile, Fulgencio moved up their lesson, teaching it the following day between lunch and dinner. Never had he spoken such lucid, unadorned words. And that’s how it should be; it was the chapter on the existence of man, a profoundly metaphysical lesson, in which it was necessary to take everything into consideration and examine it from all sides.

“Are you getting all this?” he asked.

“Perfectly.”

The old man continued until he came to the end of the lesson. When it was over, the same thing happened as on the day before: Caetaninha was afraid of being alone and asked him to continue his lesson or go for a walk. The old man said no to both, patted her head paternally, and locked himself up in his study.

“Next week,” thought the old doctor, as he turned the key, “next week I’ll start the lesson on the organization of societies, then spend all next month and the one after that on the definition and classification of the passions. Then in May, we’ll turn to love… the time will be right for…”

While he was saying this to himself and locking the door, there was a sound out by the porch – a thunderous roar of kisses, according to the caterpillars out by the barn. But, then again, any little noise sounds like thunder to a caterpillar. As for the true authors of the noise, nothing is known for sure. It seems that a wasp, who saw Caetaninha and Raimundo together at that very moment, inferred consequence from coincidence and assumed it was they who made the sound; but an old grasshopper demonstrated the inanity of the foundation of his argument, pointing out that he had heard plenty of kisses in his time, in places where neither Raimundo nor Caetaninha had ever set foot. We can all agree that this second argument is absolutely worthless. But such is the influence of a good reputation, that the grasshopper was applauded for having defended, once again, truth and reason. And maybe that’s the case. But a thunderous roar of kisses? Let’s suppose there were just two, or perhaps three or four.

From Selected Stories, translated by Rhett McNeil and published by Dalkey Archive Press.

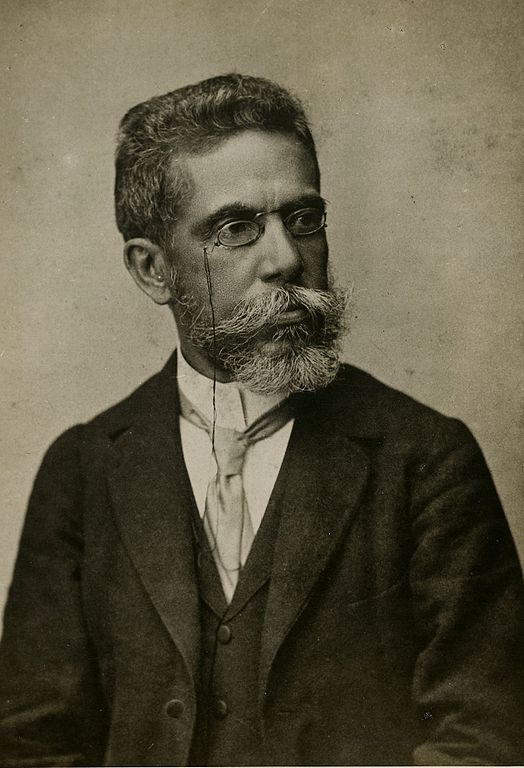

Joaquim Maria Machado de Assis (1839–1908) was born in Rio de Janeiro, the son of a mulatto wall painter and an Azorean Portuguese washerwoman. Beginning as a writer of poetry and romantic fiction, in middle age he created novels and stories marked by playful self-reflexivity and pitch-dark pessimism. Widely regarded as the greatest writer in Brazilian literature, he was accorded a state funeral with full civil and military honours, a first in that country for a man of letters. Read more.

Joaquim Maria Machado de Assis (1839–1908) was born in Rio de Janeiro, the son of a mulatto wall painter and an Azorean Portuguese washerwoman. Beginning as a writer of poetry and romantic fiction, in middle age he created novels and stories marked by playful self-reflexivity and pitch-dark pessimism. Widely regarded as the greatest writer in Brazilian literature, he was accorded a state funeral with full civil and military honours, a first in that country for a man of letters. Read more.

Portrait of the author c. 1896, photographer unknown. Fundação Biblioteca Nacional/Wikimedia Commons

Rhett McNeil is a scholar, critic and literary translator from Texas, where he graduated from UT-Austin with degrees in English, Portuguese and Art History. He is currently completing a PhD in Comparative Literature at Penn State University. His translations from Spanish and Portuguese include novels and short stories by Antônio Lobo Antunes, Enrique Vila-Matas, Gonçalo M. Tavares, João Almino and A.G. Porta.