Animal scruples

by Jean de La FontaineTwo poems from La Fontaine’s Selected Fables, relating that the natures of two-legged and four-legged creatures have a great deal in common. From a delightful new translation with an introduction and explanatory notes by Christopher Betts published by Oxford University Press, and illustrated throughout with Gustave Doré’s exquisite original engravings.

The rat and the elephant

Among the French, large numbers are inclined

to think themselves important; many act

like men of consequence; they are in fact

no more than persons of the bourgeois kind.

To silly vanity, we are extremely prone:

it truly is the French disease, 1 our very own.

Spaniards are vain, but in another way;

their pride, although less foolish, seems in short

to be the wild fantastic sort.

Our kind is what my characters portray;

it’s worth no less than other kinds, I’d say.

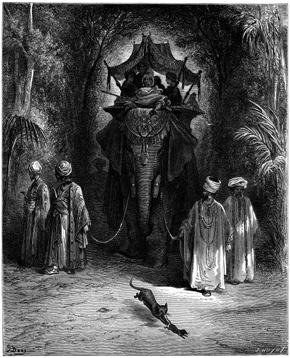

A very little rat once chanced to see

an elephant as large as large could be.

He watched the animal of high estate

and mocked its slow and solemn gait.

Upon the triple-tiered creature rode

a maharanee of renown

on pilgrimage towards a holy town.

Her household added to the load:

her dog, her cat, her cockatoo,

her lady’s maid, her monkey too.

The rat professed to feel surprise

that people should admire this massive hulk.

“As if ,” he said, “importance should arise

from filling up more space with greater bulk.

Why are you humans awed to see this sight?

Because its size gives children such a fright?

But in us rats, the fact of being small

does not reduce our self-esteem at all.”

He hadn’t finished, but the cat, up high,

had left her cage and down she came;

she taught him in an instant why

it isn’t sensible to claim

that rats and elephants are just the same.

Book VIII.15

The wolf and the shepherds

A wolf in whom humanity held sway

(if such can be, in such a breed)

reflected deep and long one day

on all the cruel things he ’d done,

albeit forced on him by need.

“They hate me, all of them,” he said, “bar none:

wolves are public enemy number one.

In villages men meet with horse and hound

to hunt us down, and Jupiter on high

is deafened with the hue and cry.

In England not a wolf is to be found: 2

by order, killing wolves has earned a fee.

So local squires, one and all,

attack us with the same decree,

while mothers threaten, if their children bawl,

to give them to the wolf for tea.

And what is all this fuss about?

Some scabby donkey or some poxy sheep,

some snarling cur. Such morsels they can keep:

not food for me; I’d sooner go without.

So be it then: henceforth I shall abstain

from eating creatures that have life and breath.

I’ll browse instead, and live on grass and grain;

Or rather, starve and die. Is such a death

so cruel? Better that, at any rate,

than facing universal hate.”

Portrait of La Fontaine by Hyacinthe Rigaud (1659–1743)

Some shepherds were nearby, and when he looked,

he saw them eating meat that they had cooked:

they’d grilled some lamb. “Now, what ’s all this?” he said;

“I blame myself for all the blood I shed,

while those who have these creatures in their care

devour them? And they give their dogs a share!

Must I then scruple still, wolf that I am,

to take my meat? By all the gods, not so!

I’d look absurd. I’ll have that little lamb:

no need to cook him, down my throat he’ll go;

so will the mother suckling him, that ewe.

I’ll have the ram his father too.”

This wolf was right: is there a law to say

that we can gorge ourselves on any prey,

take animals for food, while they retreat

back to the Golden Age, forgoing meat? 3

No grills or cooking-pots for them, say you?—

shepherds, reflect: the wolf is only wrong

when he is weak and you are strong.

Why should he live as hermits do?

Book X.5

1 LF’s readers would have known that, whereas in France venereal disease was dubbed ‘the Naples disease’ (‘le mal de Naples’), it was ‘the French disease’ in Italian parlance.

2 By a decree of King Edgar’s in the 10th century, tribute due to Welsh princes could be paid in wolf’s heads rather than money, which led to the wolves’ destruction.

3 In the ancient poets’ first age of mankind, one of perfect contentment, men had supposedly been vegetarian.

Jean de La Fontaine (1621–95) made his mark as a poet in the court of Louis XIV, first winning acclaim for his Contes, scurrilous tales from writers such as Boccaccio retold in rhyme. The Fables, derived from Aesop and a range of Oriental sources, were first published in twelve books between 1668 and 1693. Their popularity was immediate and they remain some of the greatest and best-loved poetic work in French. In old age he disavowed the Contes, and on his death was found to be wearing a hair shirt.

Christopher Betts was senior lecturer in French Studies at the University of Warwick until his retirement. His previous translations include Montesquieu’s Persian Letters, Rousseau’s Social Contract and Perrault’s Complete Fairy Tales.

Read more.