The eye of the Tigris

by Ruqaya IzzidienThe present is an arrogant time in which to live, always has been. Humans of the present look back at their people, land, and history, and whisper to themselves with glee, We are not them. But we were always them. We are our history; we are the crimes of our ancestors. And we wait, mouths agape, to hear tales of hope, as though good could triumph in such a world.

But every century, every desperate land, every present, has its own moment of optimism, an instant in which its people are so sure, just like their fathers before them, that something better is possible. They tell themselves that their souls are better now, more compassionate, more powerful. This time it will be different.

So, even when he was lost, face down in the sludge, still unconscious, the man on the banks of the River Tigris would come to believe it too. Proof that even when a person has no name, no memory, and no idea how he ended up on the shores of Baghdad, hope can prevail. Yes, humans have a long history of mistaking desperation for courage.

And when he felt a prod in his back, his body aching, his mind flooded with unanswered questions – none of it took away his unshakable belief that, eventually, all would be well.

“Told you he wasn’t dead, Mariam. Told you,” someone shrieked, as the man heard small feet thumping into the distance. He sat up, blinking river dirt out of his eyes.

“Wait,” he said, with a grunt that shocked even himself.

The sun disappeared behind two figures standing over him. He rubbed his eyes and squinted up at them. The sky was obscured by two pairs of large beetle eyes, made wider by thick black outlines that shaped them into lemons, and by four braids, half twisted into folds of gray cloth. The smaller girl broke the silence with a squeal that wobbled her oversized cheeks.

“Are you all right?” asked Mariam, politely. “I… we thought maybe you needed help. Should I fetch my baba?”

“No. Where am I?” he tried to whisper, but it came out as a growl.

“Nahar Street is that way,” she said, pointing.

‘Are you a soldier, Ammu?’ she asked gently, indicating his belt’s insignia. He looked down and his hands darted around his muddied uniform. ‘Then how did you come to be here?’”

“Baghdad?” he asked. She nodded, and he thought she spoke again – though he couldn’t be sure. He stood up, swaying, his head throbbing. He rubbed at the dirt dried to his chest and slapped at his sleeves. For a second he remembered, and was sure he saw his companion and his horse on the bank across the Tigris.

“Bring my horse around, would you, Karim?” he called across the river. “And, no, we can’t take turns riding him. I don’t care what your story says – he’ll not end up in the river if I can help it.” The man threw back his head and laughed. “See how well I know you, Karim.”

The girls exchanged a glance.

“Let’s go, Salsabeel. He’s crazy,” said Mariam, walking away.

“Look!” said Salsabeel, pulling on her friend’s sleeve, using the full force of her plump form to drag them both back to the man. He was standing, still swaying slightly, and examining the river. “Are you a soldier, Ammu?” she asked gently, indicating his belt’s insignia. He looked down and his hands darted around his muddied uniform. “Then how did you come to be here, in the mud?”

His breathing quickened and he clasped his hands together to stop them shaking.

He turned with a slight wobble and shook his head with a gasp.

And then he ran.

Winter 1915

Baghdad

He ran. He wasn’t sure if his legs were heavy from the clay of the Tigris or from the ache of the cuts it surely concealed, but he ran anyway. His hair was matted with sand and dirt, and the thumping in his head made him feel like a man was running behind him, playing the tabla drum on the back of his skull.

He flicked his eyes as he ran, inspecting the alleys on either side for any trace of the familiar. He found himself in a narrow street lined with shanasheel oriel windows, their wooden panels knotted into webs of hexadecagonal stars and tesselated honeycombs. He ran past ten, eleven shanasheel, each betraying its hidden residents with the gravelly clank of a clay water flask, the tittering of gossip, or wafts of earthy tea. Something about the tea tugged in the man’s stomach; it was a memory he could not quite place, but it was a comforting sensation, he thought. Why, then, did it fill his chest with such an ache? He put a hand against the street’s stone wall and shut his eyes for a moment.

He caught only flashes of the scenes in front of him: reams of smoke trailing up from an open-air stone oven, the green woven belt of a passing man, but most of all it was the eyes – everywhere he looked, flashes of eyes – curious, amused, and disapproving. A huddle of women, with visors peeping out under their veils, stared at him as they hurried by, before averting their eyes from him – with some terror, he thought. Maybe this was it. Would he roam these streets forever, aching with this unshakable sense of absence? It was surprisingly painful to feel loss and not recall where to place it. He even considered for a moment if this was his journey to the afterlife. He tugged at his belt and pulled it up a little higher on his waist. Whatever had happened to him, whatever the reason he was coated in days-old dirt and reeked like a butcher’s cast-offs, he was still here. And it brought him relief when he told himself he had defeated the odds, unknown as those odds were. He would remember, he had to, or what was the point of it all?

And he swore then that if he had to run every inch of Baghdad, he would remember.

He wound around unfamiliar alleys and passed crooked homes. Like the flashes of a moving picture, he watched a magenta and cobalt minaret disappear over his shoulder and found himself inside the tubular hall of Baghdad’s weavers’ bazaar, where the horizon disappeared behind an infinite stream of stone arches. Bold rugs were suspended from iron hooks, and each merchant marked his territory with the display of his most intricate creation on the wall above his workshop, as he sweated below. Scores of weavers worked in counterbeats, deftly tossing shuttles of wool through dancing pins, and tapping their pedals in a rhythmic jig. He felt himself in a colony of praying mantises, as the workers bobbed their bent heads and spread their arms in an embrace of their looms.

He wound through the carpet of shredded wool, kicking up a multicolored wake. As he passed each stone arch, another appeared on the horizon. And, God, the stench. Had Baghdad always smelled so bad?”

Light beamed in from looming windows casting a haze on the thread cobwebs that zigzagged around the weavers, and making the floor of discarded fibers in the window’s glare light up with a dusty glow. A sea of Baghdadis careened down the bazaar: men in dishdasha robes and suit jackets clenching their wares under their arms, women with bejeweled braids, and others, cloaked in warrior black from head to toe, their suspended huntress faces gleaming as they eyed the market stalls. He wound through the carpet of shredded wool, kicking up a multicolored wake. As he passed each stone arch, another appeared on the horizon. And, God, the stench. Had Baghdad always smelled so bad? He filled his lungs with the reek of sweat and piss and sourness that had fermented in the heat and sand for weeks. He pinched his eyes shut and let his legs and ears navigate. Shoppers called out angrily as he jostled them but he kept his eyes sealed, stopping only when he felt the sun warm his forehead.

“May I shave your face, sir?” a street merchant called to him as he exited the bazaar. “That beard is a veritable beehive. Let me see to it.”

“Take your photo?” another yelled from across the road. A crowd of shoppers tussled past.

The man slumped to the floor and leaned against the teardrop archway of Baghdad city’s North Gate.

“Some syrupy hot zalabya, sir? The best this side of Baghdad,” said a man from beyond the gateway. “I can see you’re in need of a—”

But the man would never know what it seemed he needed.

He covered his ears and filled his lungs. “Enough!” he said. He put his head to his knees and rocked, humming his favorite Sherif Muhiddin melody. He heard laughter and mocking murmurs, which only grew louder as he tried to drown them with his humming.

“It’s all right,” he told himself. “I will remember and it will be all right.” He heard a woman yell, but he kept rocking, thinking of the sluggish, sorrowful oud, sharing the musician’s epic as his own tragedy.

“A madman!” a woman shouted. If he had opened his eyes, he would have wondered why tears had erupted onto her cheeks, but all he heard were the unrelenting accusations that he was a madman, pelting him from the gateway.

He shut his eyes and hummed his melody, loudly enough to block out all else.

“Mad!” she yelled. Then, after a few moments, she took him by the shoulders and began humming the tune with him.

He opened his eyes and dropped his arms, the dried mud on his face now moist again. The woman crouched beside him, and he knew he had been mistaken: a person with a face as kind as hers could never have called him mad.

“Ahmad!” she gasped, her eyes shining. “I found you, Ahmad.”

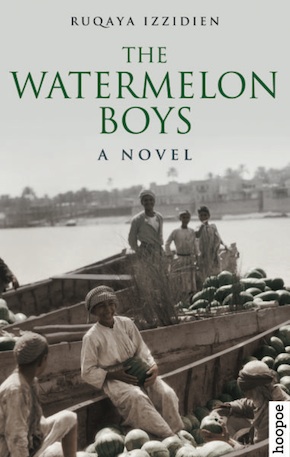

from The Watermelon Boys (Hoopoe, £9.99)

Ruqaya Izzidien is an Iraqi-Welsh freelance journalist and writer currently based in Morocco. Since graduating from Durham University she has also lived and worked in Cairo and the Gaza Strip. The Watermelon Boys is out now in paperback from Hoopoe.

Ruqaya Izzidien is an Iraqi-Welsh freelance journalist and writer currently based in Morocco. Since graduating from Durham University she has also lived and worked in Cairo and the Gaza Strip. The Watermelon Boys is out now in paperback from Hoopoe.

Read more

ruqayaizzidien.com

@RuqayaIzzidien

“It might recount a series of brutal conflicts and betrayals, but it is, ultimately, a novel defined by love and moral conviction… Izzidien’s great triumph is to illustrate how nuanced and knotty history can be – and why it matters that we recognise this.” The National