Far more darkness than the eye can fathom

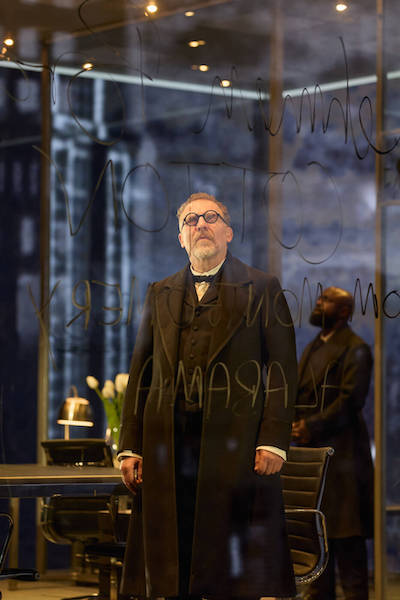

by Mika Provata-CarloneTake your seat – preferably, if you can, in the centre stalls, for a commanding, birds-eye panoramic view of the spectacular stage that Es Devlin has created for Sam Mendes’ National Theatre production of The Lehman Trilogy, currently at the Gillian Lynne Theatre in London. As the lights switch on, you will find yourself in an existential space-time warp: the fourth-wall illusion has been eliminated, or, rather, it has been cannily replaced by a totalising glass cubicle representing a contemporary Wall Street office suite, where walls intersect, creating forbidding and restraining boundaries, as well as spaces of complete and unmitigated exposure. The colour scheme throughout the play is strictly white and black, with no grey areas or any other colours (except for an immortal and immortalised bunch of flowers). The intended visual symbolism is unmistakable, stark, pervasive: The Lehman Trilogy will grant audiences, or so it claims, full black-and-white transparency as to the history, and especially the agency and liability, of the Lehman family and its banking legacy and practice as regards the catastrophic financial crisis of recent years. The devastating crisis that transcends economic ramifications, and is deemed to have abraded every aspect and layer of our society. The Lehman Trilogy from the outset posits itself as a full-throttled J’Accuse, and a resounding, a literally booming, QED.

Into that space, a solitary figure performs gestures and actions that have become disturbingly familiar: filing boxes are being filled, an office space is being emptied, failure and collapse of an individual or a financial entity is the tacit subtext of the tableau. The figure leaves. He will not be seen again. Mendes relies on an austere, super-powerful symmetry of action and inaction, absence and presence to deliver his message. A veritable tempestarius, he summons a one actor-three actors-many actors storm with great panache and military precision, in an all-powerful mathematical formula of symmetry of 1-3-∞: it will ensure both total empathy as well as totalising dissociation, a proclamation of individual identification, single-group accountability, and a claim to a collective catharsis.

The stage is soon populated by three figures, who will not leave it, even though they will not remain the same. They are superbly Protean, a Biblical continuum of sameness and difference, and retaining their original costume throughout, as a crucial reminder of first origins and original causes. The first figure to appear stands in what has become in recent years a rather popular, stereotypical theatrical pose: legs apart, feet in parallel, torso thrust forward, shoulders defiantly slanted back, head tilted upwards and eyes staring ahead, towards an indeterminate void or immensity, creating out of thin air a full compendium of the body language of solid self-empowerment, of the projected personal narrative, of the claim to one’s own mighty voice. Also of a certain level of ham acting, if badly handled.

This first figure is Haim Lehman, who arrives in New York in 1844 from Germany and becomes, in the blink of an eyelid (or through the irrefutable social eugenics of the Port Authority officials), a fully (?) Americanised, reborn, messianic Harry. As he declares, Baruch Hashem! Blessed be God. His two brothers, Mayer and Emanuel, follow suit, and the schema (or the scheming device) that connects them and defines them is proclaimed time and time again, a concept to be hammered into the minds and consciousnesses of the audience: Henry is the head; Emanuel is the arm; Mayer is the mediator between the two, a mechanism of leverage and brokerage that, as the relentless rhythm and pace of the play profess to make clear, has been set up with the deliberate intention of absolute rule and domination.

Part One contains all the elements that will determine the whole: a supremacist use of microfocus which renders all contextual analysis and questioning impossible.”

Part One of The Trilogy tells the story of the three brothers in Alabama, their progression from storekeepers to cotton traders, to brokers, to owners of a banking empire that apparently ruled and ruined the entire world. It contains all the elements that will determine the whole: a supremacist use of microfocus which renders all contextual analysis and questioning impossible, and especially ostensibly irrelevant. There is no external or alternative viewpoint, no Hippolyte Taine pervading environment, no objective correlative, except a chronological cinematic backdrop of dramatic historical events, which seem particularly susceptible to the concept of space-time bending and frame dragging – thus enhancing the impression of the massive gravitational pull of the Lehman family, and the solitary primacy of its own trajectory. Equally deterministic is the unremitting cut-to-the-chase mode of narrative and plot, which ensures total control of the angle of interpretation, of the critical perspective, and especially of audience response; also a ‘type’-centred representation, allegedly for the sake of dramatic emphasis and clarity. This unfailingly plays on tropes which if transposed to, say, for the sake of argument, Germany in the 1930s, would certainly reek of antisemitism: religious observation is paired with professional and social categorisation, caricatural portrayals of ethnic customs and group traditions are given an ominous veneer of effervescence, which belies their function as carriers of a subliminal messaging system. The projected image of the Jew that we are given is of a hardworking arrivistic strategist, a word also boomed into audience ears; he is stingy and flashy, ambitious and vulgar, and has an uncanny instinct for turning disaster into profit, uncertainty into opportunity. After the economic collapse of the Southern States following the American Civil War, the three brothers emerge, or so the play tells us, as the force that transforms both finance and ruins. Their power of persuasion is not argument, but a bewitching, mesmeric, and hypnotic smile, which casts a spell on the unsuspecting ‘indigenous colonials’. Throughout the play, there is not a single character who is not ‘foreign’ or Jewish, except for those so-called victims of such mysterious, perfidious mesmerism.

Women, the Lehman wives, are masterpieces of gender bigotry, and sex-goddess, angel-in-the-house, or ‘the bearded lady’ sexual politics. The issue is not that they are being portrayed by male actors; the conceit of using a cast of only three to conjure up more than 150 years of world and family history is a sheer stroke of genius on Mendes’ part, as is the purely dramaturgical aspect of the production, which is nothing less than breathtakingly brilliant. The vital issue concerns the modulations of body language, the deliberately falsetto vocal inflections and simian facial expressions, and the meta-narratological allusions to drag depictions of femininity, to a historic vocabulary of misogyny that is cultural, visual and socio-political, and to which we owe the genera of the virago, the hag, the fortune hunter, the harridan and the overbearing matriarch, the shrew, the vixen and the airheaded bimbo, and so much else.

The acting by Nigel Lindsay (Henry), Hadley Fraser (Mayer) and Michael Balogun (Emanuel) underscores the ‘now listen to me’, ‘mark my words’, and above all the ‘I give you the Beginning and the Word’ thrust that operates throughout. Dialogues are muscular, staccato and stentorian, both when direct exchanges take place, and when an omniscient narrator voiceover takes the reins, claiming full authority. The sheer tempo and garishly loud volume of the speechifications impose a sense of inescapability on all meaning assignation, a Big Brother urgency not to stand in the way of the master narrative that is here being promoted. Yet resist the ‘zone’ effect, and the glass of the cubicle shatters, the smartness of the script loses its semantic sparkle and polished edge, the claims of transparency go up in murky, grimy, unmistakably grey smoke.

As the play ends, the scapegoat has been found, caught, tried and dully punished, the blame is lifted, the damned spot finally rubbed off. The audience can breathe a sigh of mass relief.”

Parts Two and Three add more biographical couleur locale, but not much substance. The whirlwind of voracious success, the intrepid torrent of ostentation, presumption, hubris and bourgeois gentilhomme self-creation of the next generation(s) takes centre stage, against the background of the industrial boom, the economic crash, the gilded golden age of the 80s and 90s. More (un)subtle signifiers are dextrously embedded in the intended collective response: pianos and violins, poseur affectations, higher education turned into cut-throat business acumen, aspirations to high culture, refinement and connoisseur art collecting, discerning fashion statements and Grands Tours in Europe, a whole panoply of nouveau-richisme, as well as the values of a very real and substantial, vital and Western cultural landscape, are wholesale and liberally, ferociously and pointedly pilloried en masse, without any critical distinction or differentiation. Xenophobia becomes overt and explicit, as two new characters are given their own parochialised, stereotyped, troped histories, a Greek and a Hungarian. The Greek is oily (the homonyms ‘Greece/grease’ are a perennial hellenophobic slur), hardworking, by-the-book honest, assimilated as soon as the second generation gets a chance; the Hungarian remains Hungarian, unrepentant for his dog-eat-dog mentality and self-serving ruthlessness, proud of his boorishness, brutishness and professional brutality. The Greek and the Hungarian take over the stigma of ancestral guilt and original sin, carry forward the proposed model of intrinsic strategy of evil to its final, expected conclusion, the collapse of Lehman Brothers which would trigger perhaps the most momentous financial crisis in recent history.

As the play ends, the stage now fills up with an army of humanity, a jury of witnesses to this collective rite of trial and expurgation. From the single figure of the innocent janitor of the opening scene, the private, unimplicated individual suffering unjustly for the sins of mighty others, we have moved to a purported cathartic moment of collective expiation: the scapegoat has been found, caught, tried and dully punished, the blame is lifted, the damned spot finally rubbed off. The audience can breathe a sigh of mass relief, there is no miasma left, no more soul-searching, due diligence, or atonement to be done, all is accounted for. A single family, a single bank, a single thread in our complex and implicated history, are identified and thrust out as the sole culprit, corruptor and contaminant. Sounds familiar?

That Lehman Brothers had a notorious history of ruthless financial practices is no news, and it is a glaring fact; that it maximised those practices, monetised unscrupulousness, and thrilled at cosmetic accounting hocus-pocus and house-of-cards-leveraging is, again, rock solid, indisputable reality. Lamentably, troublingly, highly problematically, The Lehman Trilogy interweaves with any historical, judicial or technical analysis of that rock-solid, criminal culpability and gross public liability the caricaturised and systemically troped personal and ethnic characterisation of a family and a selection of its constituent individuals. It employs an ineluctable linearity of causation, from Haim to Robert Lehman, to create an insular and absolute deterministic genealogy of insidious deliberation, in which Jewishness and foreignness are organic operative factors and critical operators. The ethnic and religious stereotypes in The Lehman Trilogy cannot be explained away as having been historically and systemic there: there is no external position for them in the play, nor are they ever merely descriptive, in a Fiddler on the Roof or Yentl kind of way. As codified here, it is not possible to ascribe any of them to what Leon Pinsker termed historic Judeophobia, or to anything else, except to what is here suggested as an inerasable, Jewish, ‘nature’. In The Lehman Trilogy they are presumed to be, and are imposed as archetypes, and that has serious consequences as well as horrific antecedents. The Lehman Trilogy injects an innate xenophobic subtext to the explanation it offers, and indulges in blatantly misogynistic stock-imaging in order to beguile its audience into uncritical complicity. Close your eyes to these elements, and the play is a tour-de-force of how the insignificant brought about the fall of an era and the misery of millions; stare hard at these organic features of Ben Power’s adaptation of Stefano Massini’s story, and you might perhaps start wondering, quite anxiously, as to what it all might mean, beyond the surface of its words, worlds on a stage, and cries in its financial wilderness.

—

The Lehman Trilogy continues at the Gillian Lynne Theatre to 20 May.

More info

@LehmanTrilogy

@NationalTheatre

@NealStProds

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.

bookanista.com/author/mika/