Fight your own war

by William Saroyan

I am sitting in this small room, two or three months from now or two or three years from now, writing a story about a number of human beings marching in a hunger parade and writing about what is going on in their minds, about all the remarkable things they are dreaming and imagining in connection with themselves and the universe, when I hear a knock at my door, a very emphatic knock.

I know it isn’t opportunity because opportunity knocked at my door a number of years ago when I was out, looking for a job, so I imagine it must be my cousin Kirk Minor, the best writer I know who does not write and does not want to write. Or else, I imagine, it is that young man with the sad face and the ragged blue serge suit who works for the collection agency and comes to my room once a month to inform me politely and nervously that unless I cough up with those four dollars I still owe that employment agency that got me a job in 1927 the case will be taken to court and I will be disgraced, and maybe sent to the penitentiary.

This young man has been coming around to my room so often that I know him very well and in a roundabout way we have come to be friends, even though on the surface we may appear to be enemies. I never did bother to ask him his name but he has told me all about himself and I know he has a wife and a young daughter who is always ill and a source of great worry.

At first I used to dislike this young man and I used to wonder why he worked for such a company as a collection agency, but when he explained about his little sick daughter I began to understand that he had to earn money somehow and that he wasn’t doing it because he liked to do it, but merely because it was absolutely, almost frantically, necessary. He used to come into my room, melancholy with worry, and he used to try to look at me severely, and then he would say: See here, Mr. Sturiza, my firm is becoming very tired of your evasions, and we must have a full settlement at once. And I used to say: Sit down. Have a cigarette. How is your daughter? Then the young collector used to sigh and sit down and light a cigarette. Duty is duty, he used to begin, and I’ve got to be severe with you. After all, you owe our client four dollars. All right, I used to say, be severe. I don’t owe anybody a dime. I owe my cousin Kirk Minor a half dollar, but he hasn’t taken the case to an agency. Then we used to talk for about a half hour or so, and the young collector used to tell me his troubles, how bad it was with him, and I used to tell him my troubles, how bad it was with me, wanting to write well and always putting down the wrong thing, and then having to go out and walk to the public library to try to find out again how Flaubert did it.

The knock destroys the continuity of my thought, and I go to the door and open it. If it is my cousin Kirk, I think, I will reprimand him; if it is the young man from the collection agency, I will be polite, and I will ask about his daughter.

Enrico Sturiza? he asks, only he shouts it, and I begin to understand that something has happened somewhere in the world, something momentous, historic.”

It is neither, however; it is a small man of fifty with a dull face animated momentarily by some exciting thought, and in his left hand is a large brown envelope, stuffed, no doubt, with very important documents. The man is a stranger to me, therefore I am greatly interested in him, hoping to be able to learn enough about him to write a good short story.

Enrico Sturiza? he asks, only he shouts it, and I begin to understand that something has happened somewhere in the world, something momentous, historic.

Yes, sir, I reply quietly.

Enrico Sturiza, continues the small man in a manner that suggests that I am about to be sentenced to death for some petty and forgotten misdemeanor, I have the distinguished honor to inform you, on behalf of the International League for the Preservation of Democracy and the Annihilation of Fascism, Bolshevism, Communism and Anarchism, that you are eligible for active duty in the front line, and that as soon as you are able to get your hat and coat I shall be pleased to escort you in the Packard downstairs to the regimental headquarters. There you will be furnished a brand new uniform, a small book of instructions written in language comprehensible even to seven-year-olds, a good gun and a place to sleep.

The small man has made this speech in a lively and impressive style, but I am not greatly impressed. I pause, light a cigarette and suggest that my guest enter my room and sit down. He enters my room, but declines the chair.

Is there a war? I ask politely.

Yes, of course, smiles the small man, implying that I must be a dunce not to know. War, he announces, was declared this morning at exactly a quarter past six.

That’s no hour to be declaring war, I reply. Hardly anyone is awake at that hour. Who did the declaring?

This question disturbs the small man, and he blushes with confusion, making a face and attempting a cough.

The full and written declaration of war was printed in all the morning papers, he replies.

I don’t read the papers, I reply. I sometimes glance at the Christian Science Monitor, but not often. I am a writer, and reading newspapers spoils my style. I cannot afford to do it. But the war interests me. Who wrote the declaration?

The small man does not like me, and he refuses even to attempt to answer my question.

Are you Enrico Sturiza? he asks again.

I am, I reply.

Very well then, come with me, says the small man.

I am sorry, I reply. I am writing a short story about hungry people marching in a parade, and I must finish the story today. I cannot come with you. After I finish the story, I must walk to the Pacific Ocean for exercise.

I demand, says the small man, that you come with me. In the name of the International League, I demand that you come with me.

Get the hell out of here, I reply quietly.

The small man begins to tremble with rage, and I begin to fear that he will have some sort of fit. He turns, however, in a military manner, shouts that I am a traitor, and departs.

I return to my typewriter and try to go on with the story I am writing, but it is not easy to do so. A war is a war, and everybody knows how viciously the last war got on the nerves of writers, bringing about all sorts of eccentric styles of writing, all sorts of mannerisms. News of the war upsets me, and I begin to mope, sitting idly in my chair, trying to think of something intelligent to think.

In not more than a half hour there is another knock at my door, and opening it I look upon the handsome figure of a young man in an officer’s uniform. He is obviously a well-bred sort of chap, through the university, cheerful, and not altogether an idiot.

Enrico Sturiza? he asks.

Yes, I reply. Please come in.

My name, says the young officer offering me his hand, is Gerald Appleby.

I am very pleased to know your name, I reply. Will you be seated?

Young Mr. Appleby accepts my hospitality, produces a cigarette case, opens it; I accept one, we begin to smoke, and a conversation begins.

I am heartily in favor of a return to utter barbarism. I think it would be very good fun. I think even the most highly sophisticated people would enjoy being barbaric for a century or so.”

Mr. Covington, says Mr. Appleby, paid you a visit this morning, I am informed. His report suggests that you do not – shall I say? – do not particularly wish to be escorted by him to regimental headquarters. My commanding officer, General Egmont Pratt, has suggested that I call on you for the purpose of carrying on a conversation, with the view, we hope, of convincing you of the urgency of your participating in the present war before civilization itself is threatened.

Appleby is very interesting. He is interesting because I can see that nothing short of a war, and nothing short of a threatened civilization, could possibly lift him from the narrowness and emptiness of his life.

What makes you think civilization is being threatened? I ask him. Where did you get that idea?

Unless we crush the enemy, young Appleby replies, boyishly evading the question, civilization will be crushed, and crushed so badly that the earth will again enter a state of utter barbarism.

Which civilization are you referring to? I ask.

Our civilization, says Mr. Appleby.

I hadn’t noticed, I reply. Besides, I am heartily in favor of a return to utter barbarism. I think it would be very good fun. I think even the most highly sophisticated people would enjoy being barbaric for a century or so.

Mr. Sturiza, says the young officer, as one young man to another, I ask you to cease being flippant, and to join your brothers in the battle against the destructive forces of man which are now threatening to overthrow all the noble and decent emotions of man.

Are you sure? I ask.

We must fight for the defense of democratic traditions, and if need be we must die in the battle.

Do you want to die? I ask very politely.

For liberty, yes, replies Mr. Appleby.

I’ll tell you, then, I say, how Pascin did it. I think he did it gracefully. He got into a warm tub, gently slashed his wrists, and bled to death, painlessly and artfully. There are, of course, a number of other ways, equally artful. I would not care to recommend leaping from a skyscraper. It is a much too hurried and fidgety way, one of those modern trends in suicide. I myself do not wish to die. It is part of my plan as a writer of prose to try to live as long as possible. I hope even to outlive three or four wars. It is my plan to stay alive indefinitely.

I have no desire to destroy the enemy. I do not recognize an enemy. Who are you supposed to be fighting? Germany? France? Italy? Russia? Who? I am very fond of Germans and of the French and the Italian and the Russian.”

I cannot understand you, says Mr. Appleby. You are a strong young man. You are not ill. You have the erect posture of a soldier, and yet you pretend to wish not to engage in this war, a war which will end all wars, a war of history, an opportunity to participate in perhaps the most extraordinary event ever to happen on the face of the earth. Our air forces are perfect. Our gas and chemical divisions are prepared to destroy the enemy in wholesale lots. Our tanks are the largest, the fastest and the deadliest. Our big guns are bigger than the big guns of the enemy. Our ships outnumber by three to one the ships of the enemy. Our espionage system is functioning perfectly and every secret of the enemy is known to us. Our submarines are ready to sink every ship of the enemy. And you sit here and pretend not to care to be involved in this, the noblest war of all time.

Precisely, I reply. I have no desire to destroy the enemy. I do not recognize an enemy. Who are you supposed to be fighting? Germany? France? Italy? Russia? Who? I am very fond of Germans and of the French and the Italian and the Russian. I wouldn’t think of so much as hurting the feelings of a Russian. I am a great admirer of Dostoyevsky and Tolstoi and Turgenev and Chekhov and Andreyev and Gorky.

Mr. Appleby rises, deeply hurt. Very well then, he says. Unfortunately, we have not yet obtained the required authority to demand the participation of all able-bodied young men, but our propaganda department is working night and day and we mean to put over a general election and to win the election. It is only a question of time when all you indifferent and cowardly fellows will be in the front ranks where you belong. I assure you, Mr. Sturiza, you shall not be able to escape this war.

Maybe this fellow is right at that, I think.

Come in again sometime, I suggest, and we’ll have a little conversation about art. It is an inexhaustible subject; the more you talk about it, the more there is to say and unsay.

I return again, a bit sadly this time, to the short story I am supposed to be writing, but it is no use; the war will not allow me to write. It is like a shadow over every thought and it renders futile every hope for the future. Rather than sit and mope, I go outdoors and begin to walk, moving in the direction of the public library. I notice people, and I notice that something has come over them. They are not the way they were yesterday. It is a very subtle change, and it is hard to explain, but I can tell that they are not the same. I wonder if I am the same. Certainly I am the same, I say, but at the same time I cannot believe in what I am saying. The people, like myself, seem to be the same, but they are not. I can perceive the difference that has come over them, but I cannot identify the difference that has come over me. I am doing my best to remain the same, but in spite of my efforts it is not working very well. Each moment finds me slightly but definitely changed.

The change in the people is hysteria; it is not yet at a high pitch, but it is beginning to grow. The change in myself, I begin to hope, is not the beginning of hysteria. I am quite calm. Only I cannot deny that I am beginning to be a little angry, and unconsciously I have a desire to knock down the next young man who asks me to participate in the war; I believe unconsciously that this is the proper thing for me to do, to knock down such a fool.

In the evening I return to my room and find my cousin Kirk Minor listening to the phonograph. The music is Elegy, by Massenet, sung by Caruso. My cousin is smoking a cigarette, looking very calm, listening to the greatest singer the world has ever known, and, according to my cousin, one of the greatest men the world has ever known.

What about the war? I ask my cousin.

What about it? he replies.

How do you feel about it?

No opinions at all, says my cousin.

You’re not telling the truth, I say. How do you feel? You’re seventeen: they’ll be taking you before long. How do you feel about it?

I don’t like crowds, says my cousin.

But they’ll make you go.

No, he says. They won’t make me go. I hate walking in line. I don’t enjoy wars.

They don’t care about that, I say. They are working on the government and they will force you to go.

No, says my cousin. I will refuse.

They will put you in jail, I tell him.

Let them, I won’t care, says my cousin.

Don’t you want to fight for the perpetuation of Democracy or something like that? I ask him.

No, says my cousin. I dislike walking in an army very much. It embarrasses me. I like to walk alone.

Well, I tell him, they sent two officers out here today, and I had to insult both of them.

That’s fine, says my cousin. You didn’t start the war. Let the men who started the war fight it. You’re supposed to be a writer of stories, though I doubt it.

That’s your opinion, I tell him. Get the hell out of here; I am going to start writing again.

A week later I am visited by a very stylishly dressed young woman who talks glibly and smokes cigarettes nervously.

We are determined to have your cooperation, Mr. Sturiza, she says. We have learned that you are a writer of short stories, and we should like to have you as a member of our local propaganda department. Your work will be to write human interest stories about young men volunteering to save civilization, heroic sacrifices of mothers, wives, sisters and daughters, and so on. You will be well remunerated, and there will be many opportunities for advancement.

I’m sorry, I say, I’m no good at human interest stories.

You needn’t worry about that, says the young lady. All the forms have been scientifically devised so that the maximum of emotional effect will be established in the feelings of the public, and you simply change the names, addresses and other minor details. It is very simple.

I can imagine, I say, but I don’t want the job.

It pays fifty dollars a week, says the young woman, and you have the rank of first lieutenant. You participate in all military social functions, and let me tell you you will meet a lot of people who will be useful to you after the war.

Fifty dollars a week is more money than I ever hoped to earn, and people are very interesting to me.

I’m sorry, I say, the job doesn’t interest me.

The young woman goes away, asking me to think the matter over. She is stopping at one of the best hotels in town, and wonders if I wouldn’t care to visit her some evening for a drink and a chat. I myself wonder.

Two months later my cousin Kirk Minor comes into my room with a morning paper. In the paper is the information that all able-bodied men will be forced to participate in the war which has not been going any too well for the side which is supposed to be our side. Our casualties have been almost as great as the casualties of the enemy: approximately one million men, twice that number injured. There have been liberty loan drives, mass meetings and thick headlines for weeks.

I read the news and sit down to smoke another cigarette.

Well, I say, this means that they’re going to get me after all.

What do you intend to do? my cousin asks.

I have decided, I say, not to allow myself to become involved.

Five days later I receive a letter ordering me to be at regimental headquarters the following morning at eight. The following morning at eight I am in my room, trying to write a short story. At eleven minutes past two in the afternoon Mr. Covington, the small man who visited me first, and four other men like him enter my room. In the hall are two military policemen, and downstairs are two large and expensive automobiles.

Enrico Sturiza? says Mr. Covington.

Yes, I reply.

As chairman of the Committee for the Study of Cases of Desertion in this district, which is the 47th district of San Francisco, it is my duty to question you in regard to your failure to appear for mobilization this morning. Did you receive official letter number 247-Z?

I suppose the letter I received was official letter number 247-Z, I reply.

Did you read it?

Yes, I read it.

Then why, if you please, did you not report this morning for mobilization?

Yes, says another of the small men, why?

Yes, why? says another.

Yes, why? says the third.

The fourth, I think, is incapable of speech. He says nothing.

I had a short story to write, I reply to the Committee, and I was engaged in writing it when I was honored by your visit.

I shall have to ask you, says Mr. Covington, to make direct replies. Were you so ill that you could not report for mobilization?

No, I reply, I was very well, and still am. I never felt better in my life.

Then, says Mr. Covington, I regret to inform you that you are now under arrest as a deserter.

I am standing over my typewriter and looking down on a bundle of clean yellow paper, and I am thinking to myself this is my room and I have created a small civilization in this room, and this place is the universe to me, and I have no desire to be taken away from this place, and suddenly I know that I have struck Mr. Covington and that he has fallen to the floor of my room, and that I am doing my best to strike the other members of the Committee, and they are holding my arms, the four members of the Committee and the two military police, and the only thing I can think is why in hell don’t you bastards fight your own war, you old fogies who destroyed millions of men in the last war, why don’t you fight your own God damn wars, but I cannot say anything, and one of the members of the Committee is telling me, if Mr. Covington dies, we shall have to shoot you, Mr. Sturiza, it will be our painful duty to shoot you, Mr. Sturiza; if Mr. Covington does not die, you may get off with twenty years in the penitentiary, Mr. Sturiza, but if he dies, it will be our painful duty to shoot you; and going down the stairs this small old man is saying this to me over and over again.

—

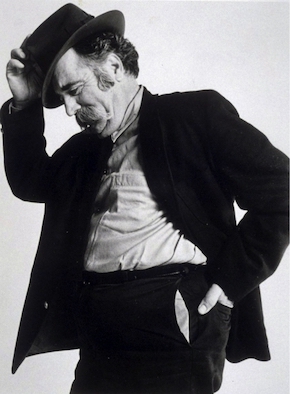

William Saroyan (1908–1981) was born in California, the son of Armenian immigrants who escaped from the genocidal Turkish Ottoman Empire. His father – a preacher and poet who became a farm labourer – died when Saroyan was three, forcing the children to be briefly placed in an orphanage. Saroyan left school at fifteen, determined to become a writer and supporting himself through odd jobs. The Daring Young Man on the Flying Trapeze, his first story collection, was an instant bestseller in 1934, and was followed by dozens of celebrated novels, stories, plays and screenplays including The Time of Your Life – for which he refused the 1939 Pulitzer Prize on the grounds that art should not be judged by commerce – and The Human Comedy, which won a 1944 Academy Award for the screenplay that he subsequently reworked as his most successful novel. In the 1940s he worked for MGM and Columbia in Hollywood, as well as travelling through the Soviet Union and Europe. He lived mainly in Paris from 1958, writing voraciously until his death. The Daring Young Man on the Flying Trapeze is reissued by Faber Editions in paperback and eBook.

Read more

williamsaroyanfoundation.org

@FaberBooks