Finding magic in the boneyard

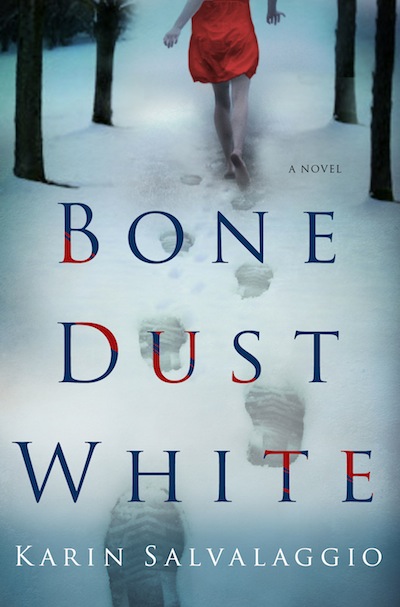

by Karin SalvalaggioI have difficulty reading for pleasure now that I’m writing full-time. This was probably brought on by the endless rewrites I did getting my first novel Bone Dust White ready for publication. I’m hoping it’s temporary, but for the time being my editor has taken up residence in my head and he will not be moved. If I read dialogue that is clunky, see a bit of exposition that smacks of hyperbole, or come across anything that doesn’t drive the plot forward I grow increasingly anxious. As you can imagine, this hypercritical approach to the page doesn’t allow me to lose myself in a book the way I used to. I now read as a form of research. In particular I reread books that have successfully tackled issues I’ve been grappling with in my own writing. For instance in my novel one of the three protagonists is a troubled young woman named Grace Adams. She keeps secrets and lives outside the boundaries of what is considered normal, but her aloofness made early drafts so frustrating that my agent wanted me to cut her point of view out altogether. I refused. I was hell bent on saving Grace. Her unorthodox worldview was important because I’d come to believe it’s what makes Bone Dust White standout as a literary thriller. The detective Macy Greeley is easy to love, but it’s Grace’s story of redemption that gives the book its soul. Readers may not warm her to her initially, but she grows in scope as the story progresses. I needed to figure out how to make my audience stick around to see that happen.

For this reason, I spent a lot of time studying Shirley Jackson’s novella We Have Always Lived in the Castle. Jackson died before its publication at just 48. Her death was a great loss to modern literature, for despite her ongoing battles with alcoholism, inner demons and obesity she was clearly at the top of her game. For those of you who haven’t been indoctrinated into the cult of Shirley Jackson, you’re in for a treat. If you’re familiar with her work already, it is always worth taking another look. She is that good. We Have Always Lived in the Castle is a haunting work of enduring genius that deserves close study. The eighteen-year-old protagonist Mary Katherine Blackwood, or Merricat as she is better known, is not only one of the most precocious voices in Western literature; she also just might be the most unreliable first-person narrator of all time. From the opening paragraph the reader is charmed by this young woman’s beguiling innocence, and even when her backstory is fully revealed we remain under her spell. A keen observer of human nature, Jackson shapes her prose into something both razor-sharp and whimsical, thereby perfectly framing Merricat’s intricate fantasy world of games, witches’ spells and twisted sisterly devotion with an air of credibility. For it is the obsessive love of her older sister Constance and the lengths to which Merricat will go to protect their increasingly fragile world which form the dark heart of this murderous tale.

Grace Adams and Merricat Blackwood are both young women who live in seclusion and are viewed with suspicion by the outside world. In the wake of past traumas, they have developed coping strategies that aren’t considered socially acceptable. In an attempt to establish a father figure and cope with her abandonment, Grace fixates on older men with whom she creates imaginary relationships. Merricat copes by living in an elaborate framework of magical spells and games to maintain order and keep outsiders away. Given how successful Jackson is at having this strange and wonderful character narrate the entire novel in the first person, I was eager to learn how she went about getting her readers onside and keeping them there. The first chapter is key. Jackson introduces her young protagonist, creates a situation that demands our sympathy, and really lets us see how she views the world:

“My name is Mary Katherine Blackwood. I am eighteen years old, and I live with my sister Constance. I have often thought that with any luck at all, I could have been born a werewolf, because the two middle fingers on both my hands are the same length, but I have had to be content with what I had. I dislike washing myself, and dogs, and noise. I like my sister Constance, and Richard Plantagenet, and Amanita phalloides, the death-cup mushroom. Everyone else in our family is dead.”

From the outset, Merricat is portrayed as a vulnerable young woman who is stunted both mentally and emotionally. It is she who braves the outside world in order to provide for her surviving family members, most of whom died six years earlier when they ate arsenic-laced sugar sprinkled on berries following a family meal. Merricat’s beloved older sister Constance is acquitted of the murders and lives as a recluse in the lush grounds of the Blackwood mansion. The local villagers have always hated the family and are disappointed that any of them survived. Merricat makes up elaborate games in her head in order to endure a morning visiting shops where she is bullied and teased. In an uncomfortable scene at a tearoom she is both verbally and physically intimidated by two local men. Afterwards she is practically chased out of the village by children who taunt her with the repeated rhyme:

“Merricat, said Connie, would you like a cup of tea?

Oh, no, said Merricat, you’ll poison me.

Merricat, said Connie, would you like to go to sleep?

Down in the boneyard ten feet deep!”

The reader is given hints that not all is well in Merricat’s mind. There is violence lurking just below the surface, but in the wake of such hostility and given that she has been drawn so sympathetically her more lured fantasies seem wholly justifiable.

“I would have liked to come into the grocery some morning and see them all… lying there crying with the pain and dying. I would then help myself to some groceries… stepping over their bodies, taking whatever I fancied from the shelves.”

Although I had a choice, I opened Bone Dust White with a chapter written in Grace’s point of view. This was risky as she is the most unreliable of the book’s three narrators, but I felt it was important that her voice was the first the reader hears. It is dreamlike and draws heavily on the allegory of Death and the Maiden, which is in strong contrast to later chapters told from the points of view of the other two protagonists. In writing the opening chapter, I drew encouragement from Jackson’s success and went to work putting into practice some of the lessons I learned from reading her work. You could almost say that I approached Grace Adams like she was a public relations project. By giving her a richer backstory and putting her in a vulnerable position I created a far more compelling character that demanded the reader’s sympathy. I made her engage with other characters in a way that was far less frustrating than seen in earlier drafts. I also let the reader know more about what was going on her head. Her initial silence was perceived as hostile. By letting people into her world and having her set the tone from the outset, readers invested in her future.

Although I had a choice, I opened Bone Dust White with a chapter written in Grace’s point of view. This was risky as she is the most unreliable of the book’s three narrators, but I felt it was important that her voice was the first the reader hears. It is dreamlike and draws heavily on the allegory of Death and the Maiden, which is in strong contrast to later chapters told from the points of view of the other two protagonists. In writing the opening chapter, I drew encouragement from Jackson’s success and went to work putting into practice some of the lessons I learned from reading her work. You could almost say that I approached Grace Adams like she was a public relations project. By giving her a richer backstory and putting her in a vulnerable position I created a far more compelling character that demanded the reader’s sympathy. I made her engage with other characters in a way that was far less frustrating than seen in earlier drafts. I also let the reader know more about what was going on her head. Her initial silence was perceived as hostile. By letting people into her world and having her set the tone from the outset, readers invested in her future.

Another issue I struggled with was the pace at which Grace’s secrets were shared with the reader and Macy Greeley, the detective working the case. We Have Always Lived in the Castle is a masterclass in the slow reveal. She drip-feeds information that either comes from overheard conversations or from Merricat herself. It was essential to get the timing of these disclosures correct. Too soon and we see no point in reading further. Not enough and we’re frustrated with the narrator’s silence and refuse to engage. Just the right amount keeps us turning the page. In a world where writers are competing with the internet, endless television channels, and smart phones with millions of apps, it’s vital that we keep our audience interested.

If you pick up a copy of Jackson’s book pay close attention to how she manages to manipulate the reader starting with those opening lines. Telling the story from Merricat’s point of view allows this fiercely unique character to not only count on our support, but gives her free rein over the world she’s created. We not only sympathise, we also accept her warped view of reality. In the end all those who enter her world must “bow… your heads to our adored [Merricat].”

Karin Salvalaggio was born in West Virginia and raised in an Air Force family, growing up on military bases around the US and overseas. She lives in London with her two children and recently completed an MA in Creative Writing at Birkbeck, University of London. Her debut novel Bone Dust White will be published in the US by Minotaur Books in May 2014. Rights have also been sold in Germany and Italy. Karin is a contributing editor at Bookanista.

Karin Salvalaggio was born in West Virginia and raised in an Air Force family, growing up on military bases around the US and overseas. She lives in London with her two children and recently completed an MA in Creative Writing at Birkbeck, University of London. Her debut novel Bone Dust White will be published in the US by Minotaur Books in May 2014. Rights have also been sold in Germany and Italy. Karin is a contributing editor at Bookanista.

Author portrait © Ross Ferguson Photography

“As jarring as a headfirst plunge in an icy river, Bone Dust White is a stark and unforgettable reading experience; its ambience, like the bruised people whose twisted lives it traces, is chilly – and irresistible.”

Julia Keller, author of A Killing in the Hills

karinsalvalaggio.com

Follow Karin on Twitter: @KarinSalvala