The Cornhill Magazine and Framley Parsonage

by Anthony TrollopeSoon after my return from the West Indies1 I was enabled to change my district in Ireland for one in England. For some time past my official work had been of a special nature, taking me out of my own district; but through all that, Dublin had been my home, and there my wife and children had lived. I had often sighed to return to England,—with a silly longing. My life in England for twenty-six years from the time of my birth to the day on which I left it, had been wretched. I had been poor, friendless, and joyless. In Ireland it had constantly been happy. I had achieved the respect of all with whom I was concerned, I had made for myself a comfortable home, and I had enjoyed many pleasures. Hunting itself was a great delight to me; and now, as I contemplated a move to England, and a house in the neighbourhood of London, I felt that hunting must be abandoned.2 Nevertheless I thought that a man who could write books ought not to live in Ireland,—ought to live within the reach of the publishers, the clubs, and the dinner-parties of the metropolis. So I made my request at headquarters, and with some little difficulty got myself appointed to the Eastern District of England,—which comprised Essex, Suffolk, Norfolk, Cambridgeshire, Huntingdonshire, and the greater part of Hertfordshire.

At this time I did not stand very well with the dominant interest at the General Post Office. In the natural course of things, I had not, from my position, anything to do with the management of affairs. I succeeded, however, in getting the English district,—which could hardly have been refused to me,—and prepared to change our residence towards the end of 1859. At the time I was writing Castle Richmond, the novel which I had sold to Messrs Chapman & Hall for £600. But there arose at this time a certain literary project which probably had a great effect upon my career. Whilst travelling on postal service abroad, or riding over the rural districts in England, or arranging the mails in Ireland,—and such for the last eighteen years had now been my life,—I had no opportunity of becoming acquainted with literary life in London. It was probably some feeling of this which had made me anxious to move my penates3 back to England. But even in Ireland, where I was still living in October 1859, I had heard of the Cornhill Magazine, which was to come out on the 1st of January 1860, under the editorship of Thackeray.

I had at this time written from time to time certain short stories, which had been published in different periodicals, and which in due time were republished under the name of Tales of All Countries. On the 23d of October 1859 I wrote to Thackeray, whom I had, I think, never then seen, offering to send him for the magazine certain of these stories. In reply to this I received two letters,—one from Messrs Smith & Elder, the proprietors of the Cornhill, dated 26th of October, and the other from the editor, written two days later. That from Mr Thackeray was as follows:—

‘36 Onslow Square, S.W.,

‘October 28th.

‘My dear Mr Trollope,—Smith & Elder have sent you their proposals; and the business part done, let me come to the pleasure, and say how very glad indeed I shall be to have you as a co-operator in our new magazine. And looking over the annexed programme, you will see whether you can’t help us in many other ways besides tale-telling. Whatever a man knows about life and its doings, that let us hear about. You must have tossed a good deal about the world, and have countless sketches in your memory and your portfolio. Please to think if you can furbish up any of these besides a novel. When events occur, and you have a good lively tale, bear us in mind. One of our chief objects in this magazine is the getting out of novel spinning, and back into the world. Don’t understand me to disparage our craft, especially your wares. I often say I am like the pastrycook, and don’t care for tarts, but prefer bread and cheese; but the public love the tarts (luckily for us), and we must bake and sell them. There was quite an excitement in my family one evening when Paterfamilias (who goes to sleep on a novel almost always when he tries it after dinner) came up-stairs into the drawing-room wide awake and calling for the second volume of The Three Clerks. I hope the Cornhill Magazine will have as pleasant a story. And the Chapmans, if they are the honest men I take them to be, I’ve no doubt have told you with what sincere liking your works have been read by yours very faithfully,

‘W. M. Thackeray.’

This was very pleasant, and so was the letter from Smith & Elder offering me £1000 for the copyright of a three-volume novel, to come out in the new magazine,—on condition that the first portion of it should be in their hands by December 12th. There was much in all this that astonished me;—in the first place the price, which was more than double what I had yet received, and nearly double that which I was about to receive from Messrs Chapman & Hall. Then there was the suddenness of the call. It was already the end of October, and a portion of the work was required to be in the printer’s hands within six weeks. Castle Richmond was indeed half written, but that was sold to Chapman. And it had already been a principle with me in my art, that no part of a novel should be published till the entire story was completed. I knew, from what I read from month to month, that this hurried publication of incompleted work was frequently, I might perhaps say always, adopted by the leading novelists of the day. That such has been the case, is proved by the fact that Dickens, Thackeray, and Mrs Gaskell died with unfinished novels, of which portions had been already published. I had not yet entered upon the system of publishing novels in parts, and therefore had never been tempted. But I was aware that an artist should keep in his hand the power of fitting the beginning of his work to the end. No doubt it is his first duty to fit the end to the beginning, and he will endeavour to do so. But he should still keep in his hands the power of remedying any defect in this respect.

‘Servetur ad imum

Qualis ab incepto processerit,’4

should be kept in view as to every character and every string of action. Your Achilles should all through, from beginning to end, be ‘impatient, fiery, ruthless, keen.’ Your Achilles, such as he is, will probably keep up his character. But your Davus5 also should be always Davus, and that is more difficult. The rustic driving his pigs to market cannot always make them travel by the exact path which he has intended for them. When some young lady at the end of a story cannot be made quite perfect in her conduct, that vivid description of angelic purity with which you laid the first lines of her portrait should be slightly toned down. I had felt that the rushing mode of publication to which the system of serial stories had given rise, and by which small parts as they were written were sent hot to the press, was injurious to the work done. If I now complied with the proposition made to me, I must act against my own principle. But such a principle becomes a tyrant if it cannot be superseded on a just occasion. If the reason be ‘tanti,’6 the principle should for the occasion be put in abeyance. I sat as judge, and decreed that the present reason was ‘tanti.’ On this my first attempt at a serial story, I thought it fit to break my own rule. I can say, however, that I have never broken it since.7

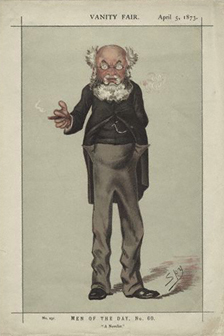

Anthony Trollope by ‘Spy’ (Leslie Ward) in Vanity Fair, 5 April 1873. National Portrait Gallery/Wikimedia Commons

But what astonished me most was the fact that at so late a day this new Cornhill Magazine should be in want of a novel! Perhaps some of my future readers will be able to remember the great expectations which were raised as to this periodical. Thackeray’s was a good name with which to conjure. The proprietors, Messrs Smith & Elder, were most liberal in their manner of initiating the work, and were able to make an expectant world of readers believe that something was to be given them for a shilling very much in excess of anything they had ever received for that or double the money. Whether these hopes were or were not fulfilled it is not for me to say, as, for the first few years of the magazine’s existence, I wrote for it more than any other one person. But such was certainly the prospect;—and how had it come to pass that, with such promises made, the editor and the proprietors were, at the end of October, without anything fixed as to what must be regarded as the chief dish in the banquet to be provided?

I fear that the answer to this question must be found in the habits of procrastination which had at that time grown upon the editor. He had, I imagine, undertaken the work himself, and had postponed its commencement till there was left to him no time for commencing. There was still, it may be said, as much time for him as for me. I think there was,—for though he had his magazine to look after, I had the Post Office. But he thought, when unable to trust his own energy, that he might rely upon that of a new recruit. He was but four years my senior in life, but he was at the top of the tree, while I was still at the bottom.

Having made up my mind to break my principle, I started at once from Dublin to London. I arrived there on the morning of Thursday, 3d of November, and left it on the evening of Friday. In the meantime I had made my agreement with Messrs Smith & Elder, and had arranged my plot. But when in London, I first went to Edward Chapman, at 193 Piccadilly. If the novel I was then writing for him would suit the Cornhill, might I consider my arrangement with him to be at an end? Yes; I might. But if that story would not suit the Cornhill, was I to consider my arrangement with him as still standing,—that agreement requiring that my MS. should be in his hands in the following March? As to that, I might do as I pleased. In our dealings together Mr Edward Chapman always acceded to every suggestion made to him. He never refused a book, and never haggled at a price. Then I hurried into the City, and had my first interview with Mr George Smith. When he heard that Castle Richmond was an Irish story, he begged that I would endeavour to frame some other for his magazine. He was sure that an Irish story would not do for a commencement;—and he suggested the Church, as though it were my peculiar subject. I told him that Castle Richmond would have to ‘come out’ while any other novel that I might write for him would be running through the magazine;—but to that he expressed himself altogether indifferent. He wanted an English tale, on English life, with a clerical flavour. On these orders I went to work, and framed what I suppose I must call the plot of Framley Parsonage.

On my journey back to Ireland, in the railway carriage, I wrote the first few pages of that story. I had got into my head an idea of what I meant to write,—a morsel of the biography of an English clergyman who should not be a bad man, but one led into temptation by his own youth and by the unclerical accidents of the life of those around him. The love of his sister for the young lord was an adjunct necessary, because there must be love in a novel. And then by placing Framley Parsonage near Barchester, I was able to fall back upon my old friends Mrs Proudie and the archdeacon. Out of these slight elements I fabricated a hodge-podge in which the real plot consisted at last simply of a girl refusing to marry the man she loved till the man’s friends agreed to accept her lovingly. Nothing could be less efficient or artistic. But the characters were so well handled, that the work from the first to the last was popular,—and was received as it went on with still increasing favour by both editor and proprietor of the magazine. The story was thoroughly English. There was a little fox-hunting and a little tuft-hunting,8 some Christian virtue and some Christian cant. There was no heroism and no villainy. There was much Church, but more love-making. And it was downright honest love,—in which there was no pretence on the part of the lady that she was too ethereal to be fond of a man, no half-and-half inclination on the part of the man to pay a certain price and no more for a pretty toy. Each of them longed for the other, and they were not ashamed to say so. Consequently they in England who were living, or had lived, the same sort of life, liked Framley Parsonage. I think myself that Lucy Robarts is perhaps the most natural English girl that I ever drew,—the most natural, at any rate, of those who have been good girls. She was not as dear to me as Kate Woodward in The Three Clerks, but I think she is more like real human life. Indeed I doubt whether such a character could be made more lifelike than Lucy Robarts.

And I will say also that in this novel there is no very weak part,—no long succession of dull pages. The production of novels in serial form forces upon the author the conviction that he should not allow himself to be tedious in any single part. I hope no reader will misunderstand me. In spite of that conviction, the writer of stories in parts will often be tedious. That I have been so myself is a fault that will lie heavy on my tombstone. But the writer when he embarks in such a business should feel that he cannot afford to have many pages skipped out of the few which are to meet the reader’s eye at the same time. Who can imagine the first half of the first volume of Waverley coming out in shilling numbers? I had realised this when I was writing Framley Parsonage; and working on the conviction which had thus come home to me, I fell into no bathos of dulness.

I subsequently came across a piece of criticism which was written on me as a novelist by a brother novelist very much greater than myself, and whose brilliant intellect and warm imagination led him to a kind of work the very opposite of mine. This was Nathaniel Hawthorne, the American, whom I did not then know, but whose works I knew. Though it praises myself highly, I will insert it here, because it certainly is true in its nature: ‘It is odd enough,’ he says, ‘that my own individual taste is for quite another class of works than those which I myself am able to write. If I were to meet with such books as mine by another writer, I don’t believe I should be able to get through them. Have you ever read the novels of Anthony Trollope? They precisely suit my taste,—solid and substantial, written on the strength of beef and through the inspiration of ale, and just as real as if some giant had hewn a great lump out of the earth and put it under a glass case, with all its inhabitants going about their daily business, and not suspecting that they were being made a show of. And these books are just as English as a beef-steak. Have they ever been tried in America? It needs an English residence to make them thoroughly comprehensible; but still I should think that human nature would give them success anywhere.’

This was dated early in 1860, and could have had no reference to Framley Parsonage; but it was as true of that work as of any that I have written. And the criticism, whether just or unjust, describes with wonderful accuracy the purport that I have ever had in view in my writing. I have always desired to ‘hew out some lump of the earth,’ and to make men and women walk upon it just as they do walk here among us,—with not more of excellence, nor with exaggerated baseness,—so that my readers might recognise human beings like to themselves, and not feel themselves to be carried away among gods or demons. If I could do this, then I thought I might succeed in impregnating the mind of the novel-reader with a feeling that honesty is the best policy; that truth prevails while falsehood fails; that a girl will be loved as she is pure, and sweet, and unselfish; that a man will be honoured as he is true, and honest, and brave of heart; that things meanly done are ugly and odious, and things nobly done beautiful and gracious. I do not say that lessons such as these may not be more grandly taught by higher flights than mine. Such lessons come to us from our greatest poets. But there are so many who will read novels and understand them, who either do not read the works of our great poets, or reading them miss the lesson! And even in prose fiction the character whom the fervid imagination of the writer has lifted somewhat into the clouds, will hardly give so plain an example to the hasty normal reader as the humbler personage whom that reader unconsciously feels to resemble himself or herself. I do think that a girl would more probably dress her own mind after Lucy Robarts than after Flora Macdonald.9

There are many who would laugh at the idea of a novelist teaching either virtue or nobility,—those, for instance, who regard the reading of novels as a sin, and those also who think it to be simply an idle pastime. They look upon the tellers of stories as among the tribe of those who pander to the wicked pleasures of a wicked world. I have regarded my art from so different a point of view that I have ever thought of myself as a preacher of sermons, and my pulpit as one which I could make both salutary and agreeable to my audience. I do believe that no girl has risen from the reading of my pages less modest than she was before, and that some may have learned from them that modesty is a charm well worth preserving. I think that no youth has been taught that in falseness and flashness is to be found the road to manliness; but some may perhaps have learned from me that it is to be found in truth and a high but gentle spirit. Such are the lessons I have striven to teach; and I have thought it might best be done by representing to my readers characters like themselves,—or to which they might liken themselves.

Of Framley Parsonage I need only further say, that as I wrote it I became more closely than ever acquainted with the new shire which I had added to the English counties. I had it all in my mind,—its roads and railroads, its towns and parishes, its members of Parliament, and the different hunts which rode over it. I knew all the great lords and their castles, the squires and their parks, the rectors and their churches. This was the fourth novel of which I had placed the scene in Barsetshire, and as I wrote it I made a map of the dear county.10 Throughout these stories there has been no name given to a fictitious site which does not represent to me a spot of which I know all the accessories, as though I had lived and wandered there.

Of Framley Parsonage I need only further say, that as I wrote it I became more closely than ever acquainted with the new shire which I had added to the English counties. I had it all in my mind,—its roads and railroads, its towns and parishes, its members of Parliament, and the different hunts which rode over it. I knew all the great lords and their castles, the squires and their parks, the rectors and their churches. This was the fourth novel of which I had placed the scene in Barsetshire, and as I wrote it I made a map of the dear county.10 Throughout these stories there has been no name given to a fictitious site which does not represent to me a spot of which I know all the accessories, as though I had lived and wandered there.

This is an edited extract from Anthony Trollope: An Autobiography and Other Writings, published by Oxford University Press, edited with an introduction and notes by Nicholas Shrimpton.

1 A high-ranking civil servant in the Post Office, Trollope had been engaged to oversee the handover of delivery services to the governors of Britain’s West Indian colonies.

2 It was not abandoned till sixteen more years had passed away (Trollope’s own footnote).

3 (Latin) ‘household gods’, figuratively ‘domestic possessions’.

4 ‘As it unfolded from the beginning, so let it remain until the end’ (Horace, Ars Poetica, II. 126–7).

5 In Ars Poetica, Horace insists that ‘Davus’ (Dave, a common name for comic slaves in Latin drama) must be as consistently characterised as heroes or gods.

6 (Italian) ‘ample’, ‘plenty’, ‘lots of’.

7 In fact, both Can You Forgive Her, published in parts from January 1864 to August 1865, and The Belton Estate (1865), serialised in The Fortnightly Review, began to appear before they were completed.

8 The sycophantic seeking of aristocratic or distinguished acquaintances.

9 Flora Macdonald was a Scottish Jacobite (1722–90) who helped Bonnie Prince Charlie to escape after his defeat at the Battle of Culloden in 1746 – though Trollope is more likely to have meant Flora MacIvor, the heroine of Scott’s Waverley (1814).

10 Trollope’s map of Barsetshire was published, ‘redrawn from the sketch map made by the novelist himself’, in Sadlier’s Trollope: A Commentary (1927).

Anthony Trollope wrote the first two chapters of An Autobiography between 20 and 30 October 1875, and completed it between 1 January and 11 April 1876. The manuscript, now in the British Library, is in Trollope’s own hand except for chapter 1 (a fair copy by his neice Florence Bland, lightly corrected by Trollope) and three inserted quotations in the hand of his wife Rose. On 30 April 1876 Trollope wrote instructing his son that the memoir be published after his death, which occurred on 6 December 1882 at the age of 67. Framley Parsonage is the fourth novel in the Chronicles of Barsetshire (Barchester Chronicles) series, all six of which are released in new editions by Oxford World’s Classics to mark Trollope 2015 bicentenary. Read more.

Nicholas Shrimpton is an Emeritus Fellow of Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford. He is the editor of Trollope’s The Prime Minister (2011) and The Warden (2014) for Oxford World’s Classics and his other publications include The Whole Music of Passion: New Essays on Swinburne (1993) and Matthew Arnold: Selected Poems (1998).