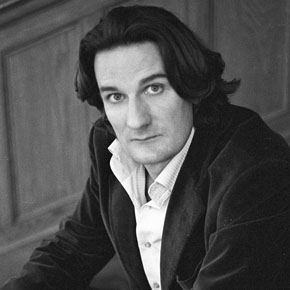

Frédéric Beigbeder: A life in fiction

by Mark ReynoldsFrédéric Beigbeder’s fictionalised biography A French Novel is a meditation on family, memory, the writing process and criminal justice. Sparked by his arrest and confinement in 2008 for snorting cocaine from a car bonnet outside a Paris nightclub, it’s an engaging reflection on an advantaged but fragmented life on the Basque coast and in the capital, and an oblique look at the identity of modern France. He talks to Mark Reynolds.

MR: France just celebrated Bastille Day. To outsiders, a big military parade on the Champs Élysées seems an odd way to mark a popular uprising. What are your feelings about the celebrations?

FB: For me it’s about the fireworks more than the military parades, but in my family a long time ago were aristocrats who had their heads cut off, so we tend to make jokes about that. I like it because we are not working on that day, but that’s about it.

MR: I’m perhaps a little envious, because Britain has never had a national day…

FB: Really? So you don’t celebrate Waterloo or Trafalgar – the defeats of Napoleon?

MR: No, the nearest is probably Remembrance Sunday, which again is all about the military. I like to think the peak of our national pride is past…

FB: Maybe that’s good, to be non-nationalist. Although yesterday I watched on TV a concert from Hyde Park where people were waving the Union Jack. So your flag is not a symbol of British pride, but punk rock.

MR: Also anything from Britpop to the Spice Girls, or a brand of training shoes… Anyway, let’s talk about the new book. A French Novel is your most autobiographical work to date, but how much is fiction and how much memoir?

FB: The thing is, it’s very weird because it’s a book written by someone who has no memory. I don’t remember my childhood. So that’s why I chose this ironic title, because I had to reconstruct and reinvent my memories like a novelist. Or like a policeman. I was asking my mother, my father, all my family about who I was. So it’s very strange, it’s an autobiography but it’s also fiction because I don’t remember what I’m telling.

My book talks about a guy who does not remember his past, but maybe it won’t be possible in the future, because you will have all your life in pictures on facebook forever, you won’t be able to forget anything. I don’t know if this is good.”

MR: Did you set out at the beginning to write a pure memoir, or was it always going to be crafted in a fictionalised way?

FB: I like to mix it up. For example in Windows on the World I told a story but also I was commenting on what a strange idea it was to write this story. It’s like people who are dying and see themselves from the ceiling, I’m always looking at what I’m doing and asking why. I don’t know if it’s normal, maybe not. I like to have an opinion on everything that’s happening. Many people wrote letters to me after this book was published in France, saying ‘I am like you, I don’t remember my childhood, I have no memory.’ I think it may be a problem with my generation: we are spoilt kids, we live only in the present, maybe hoping that we will do something in the future, but without a past, because we didn’t live through anything very important: no tragedies, we were in a peaceful country, the economy was then working well, and without war, so maybe it’s the story of a generation that has no story.

MR: That throws an interesting light on what I was going to ask next: at what age do you think a person’s character is formed? Do you think the generation born in the sixties and seventies in particular have a fixed identity that goes back to childhood?

FB: I think it was always like that. Proust was always talking about his childhood. Of course Freud explained to us that what happened in your childhood is very important. So no, the new thing is that we don’t care about our past because we think it’s not interesting. We think we didn’t live anything worth telling. I think this is the problem with my generation. Because if we compare ourselves to our parents and grandparents, they lived adventures, they had important choices to make, they had horrible things happen to them. So we are not jealous, but we are fascinated by it. I am fascinated by the generations before me, and until the police put me in a small place, I really didn’t think I had lived anything important. And maybe it’s still true, my life is not very fascinating. The thing is, even though it’s not a very interesting life, once in your life you need to tell it. You need to know it, and analyse, and I have a right to tell my story.

MR: And also to realise that any version of yourself that you project – that we all project – is fictionalised*.

FB: Of course, for example small details in this book: I had to imagine my forgotten past, and my brother, my cousins make jokes about things that I tell saying I’m a big liar, they make fun of me in my family, it’s very painful. That’s the problem with fiction: they think I’m a big liar.

MR: Does Jean-Claude Marin think you’re a big liar?

Marin was the public prosecutor who ensured Beigbeder was detained for a second night after his arrest, and is mentioned in the book as “a symbol of blind biopolitics and paternalistic prohibition.”

FB: Yes, he doesn’t like me… He was promoted, he’s now one of the most important judges in France, so we have to be very nice to him because he has a lot of power. He said on the radio when the book was first published that I was so mean to him that he did not sleep for a few nights, and so I answered ‘welcome to the club’ because he made me not sleep for two nights. I think it’s good that literature can be a revenge, like in The Count of Monte Cristo. Books are made for that: se venger, to take revenge. It’s always better if you write with anger or violence, because then I hope it won’t be boring. If you are happy, it’s more difficult to write.

MR: Your bio on the Le Figaro website describes you as a ‘dandy parisien désinvolte’. ‘Désinvolte’ translates into English as ‘casual, nonchalant, offhand or provocative’.

FB: Or lazy, also.

MR: Which is the best translation?

FB: It’s all this together. It’s partly nonchalant, lazy, and partly the kind of person who says things that appear to be light, but under the surface are very dark.

MR: And when combined with the word ‘dandy’?

FB: I don’t know if it’s an Englishman or a Frenchman who said it – it may have been Beau Brummel, but he’s both, right? he fled Britain for France – that if someone says he’s a dandy, then he’s not. So now you’re putting me in a weird position where I have to approve or disapprove, and then I cease to be what I pretend to be. It’s painful, it’s embarrassing… No, but I like the kind of writers who don’t treat anything seriously. In fact A French Novel is my first serious book, it’s more melancholic than funny, so I’m progressing, I’m becoming wiser with age.

MR: Another thing that crops up in your biographies is that your mother is always mentioned as a translator of trashy novels. How does she feel about that?

FB: She feels very bad about that, and she’d be very happy that you ask this question. She was translating Barbara Cartland. I don’t know whether in England Barbara Cartland is considered as a great novelist…

MR: She’s a figure of some ridicule…

FB: In France it’s a bit like that. So she was doing this for the money. She was not fond of her work, but she did that for a few years and then she stopped. She preferred not to work.

MR: But she hasn’t asked you to stop people from mentioning it in your biographies?

FB: No, but it’s terrible, and it’s getting worse. Now, with the internet, you cannot erase anything from your past. It’s interesting, my book talks about a guy who does not remember his past, but maybe it won’t be possible in the future, because you will have all your life in pictures on facebook forever, you won’t be able to forget anything. I don’t know if this is good. A girl gets drunk at a party, and then she is forever the drunk girl at the party.

MR: Large parts of this book are addressed to your daughter. Is she of an age yet to have read this or any of your work?

FB: She’s 14 so she could, but she doesn’t. I’m very happy with this situation. I’m very glad she does not have any curiosity about my work. I hope this will last a very long time.

MR: So she doesn’t think of you as ‘my father the writer’?

FB: No, she likes to read Twilight, and of course Harry Potter, and now she’s starting to take an interest in ‘serious’ literature, for example The Diary of Anne Frank, she’s reading that right now. And I don’t judge, I just hope she doesn’t identify too much with the character…

MR: You spent part of your childhood in the Basque country as well as Paris, and returned there over the course of 15 months to write this book. How much time do you normally spend there?

MR: You spent part of your childhood in the Basque country as well as Paris, and returned there over the course of 15 months to write this book. How much time do you normally spend there?

FB: Almost half of my time: 50 per cent in Paris and 50 per cent in Guéthary.

MR: And how much of your character would you say is formed by the Basque side rather than the Parisian side?

FB: Well, the Basques are very sincere people. If they don’t like you, they come to you and they say, “I don’t like you. What shall we do about this?” Maybe the influence on me is to be frank, to be honest. As Michel Houellebecq says in his preface, it’s an honest book. For me this is very important. Maybe I’m trying to get rid of everything phoney, and just keep simple sentences that I think are true. This is very Basque. They have a word for chance, halabeharra, which means ‘as it should be’. They are very fatalist, they think there is no hasard, nothing is random, everything is meant to be. I like that. It’s a good way never to be disappointed in life: you think, “it’s happening, so it’s supposed to happen’”, or “if it’s not happening for me, that’s normal.”

MR: Since 99 Francs (£9.99) your books have been translated by Houellebecq’s translator Frank Wynne. Did you seek him out personally, or was it the publisher’s decision to have him translate your work?

FB: Well, he translated Windows on the World, and then we got a big prize, the Independent Foreign Fiction Prize. It’s a lot of money, with 50 per cent for the translator and 50 for the writer – so of course I felt very sad to share my money with the translator. Then I became friends with him and we spent the money together drinking champagne, and now I’m very faithful to Frank. He’s not only translating, he’s also improving my work: if you read it in French, it’s not that good!

MR: Was your first translator Adriana Hunter disappointed not to work with you again?

FB: Actually I never met her. But I think we made a mistake back then to adapt 99 Francs and set it in England. It was thirteen years ago and I was so happy to be translated in English that I accepted everything, but today I think it was a mistake. For example in the French version when he goes to a nightclub he goes to Castel, and here he goes to the Groucho, but I think it’s important that he goes to Castel. But ten years ago, I don’t know why, I thought… for example André Gide, when he was translated in America, they cut all the sexual sections, because he was homosexual and it was too scandalous, and he accepted, Gide said ‘OK, you can cut it’ because he wanted to be translated in England and America. So I made the same mistake as André Gide, which is an honour for me.

MR: Is it true that you were fired from your advertising job after that book came out, or is that a convenient myth?

FB: Yes it’s true.

MR: Would you not have left anyway?

FB: Maybe I would have resigned. It’s possible, yeah. But because I’m a coward I wanted to publish the book and see what happened – and what happened is that they asked me to leave in ten minutes: “You take your things and you go now, now!” Really. It’s very strange, especially in France because it doesn’t often happen that quickly. I don’t know about the law in England, but in France firing someone is usually very slow.

MR: In the financial markets people clear their desks very quickly. In fact, in publishing it can be pretty swift too…

FB: Yes, I heard about that. I hope if people are fired at Fourth Estate it has nothing to do with the publishing of my book. Because I feel guilty, you know? I think it’s my fault. Every time I write a book, someone gets fired. Sometimes it’s me, sometimes it’s the head of my publisher, someone must pay. Somewhere there’s someone saying “OK, another Beigbeder novel: a head has to roll.”

MR: So you left advertising behind, and yet last spring you featured in a campaign for Kooples…

FB: Yes, I was very, very honoured to be asked to be a top model! What can I say? I am what I criticise, that’s the problem. In everything I write I’m always criticising myself. The idea there was funny because I did a movie, I directed my first film, Love Lasts Three Years (2011, based on his own novel), and in the Kooples image I am with my girlfriend and they say “Lara and Frédéric are together for three years, at least”, something like that. In French it’s more funny…

MR: So how did you get to direct the film?

FB: Well, in France it’s very different because we think writers can make movies. You know, since Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut were not really technicians, they were film critics and writers, and they invented the nouvelle vague, and so since then in France when you’re a successful writer you’re always asked “why don’t you make a movie?” In fact it started earlier because Sacha Guitry and Marcel Pagnol and Jean Cocteau in a way invented cinema. For example the voiceover, Sacha Guitry did a lot of that at the beginning of the last century, he was always talking to the camera and also off-camera, commenting on the images. So we have a different approach to cinema, we think it’s the dialogue and the story that’s more important, and the image can be weird and imperfect.

MR: And is it something you want to do again?

FB: It’s funny because you have sixty people helping you tell your story, and I felt it was really very comfortable, a luxury, because when you write a book you have only your own brain, and here you have sixty different brains who all have ideas, and you can steal ideas from the others. I like that, I like to be a vampire sucking the blood of the technicians and the actors. I love that because you write a dialogue and you think it’s great and then they say it and it’s not funny, it’s boring, and then they suggest something much better, but in the end when it’s in the theatre, everybody thinks it’s you who wrote this incredible line, and so everyone is congratulating me for the actor’s idea. I thought it was great, I love cinema for that.

MR: There was also a movie of 99 Francs, in which you appear onscreen (as ‘Badman’).

FB: Yes and it’s a funny thing – I’m going to brag now – the actor who played the character based on me, Jean Dujardin, got an Oscar later (for Best Actor in The Artist). So it’s almost my Oscar. It was directed by Jan Kounen and it’s very creative. There’s a lot of sex and drugs and rock ’n’ roll.

MR: Is it any different from the book?

FB: No it’s very close. It’s the story of a copywriter who has a very, how can I say, decadent life. It was a long time ago. Now I’m very academic.

MR: Max Pugh has been adapting Windows on the World too, as ‘a documentary about fiction about reality’. How’s that project going?

FB: I’ve had no news from Max for a long time. I really loved that project, I thought it was very interesting. They had the idea to make it an animation, in black and white. It was partly documentary, with archives and images of when the World Trade Center was opened, images from 1973, ’74 when it was built, and parties in the Windows on the World restaurant, and then animation to show the tragedy of 9/11. All this together, it could have been very moving. I don’t know why it didn’t work out, but they didn’t have any finance to continue, and it’s too bad. This is very common in cinema unfortunately, many projects don’t get finalised.

MR: You founded the Prix de Flore in 1994. Which winning book has given you the most pleasure, and which of the winning writers have gone on to produce the most interesting work?

FB: Ha, so you want me to be enemies with all the people I don’t mention?

MR: Yes, please now insult up to eighteen of the past winners.

FB: Eighteen enemies in one sentence. OK I like that, good challenge. Well if you look at the list we have of course very important writers like Houellebecq, Christine Angot, Amélie Nothomb, who had a lot of success afterwards and were not known before. This is important because it shows that sometimes a literary prize can be useful. And I like Nicolas Rey (Mémoire court, 2000), I don’t know if it’s translated here, it’s very melancholic. And also I like the fact that the last writers who won are very young. Marien Defalvard and Oscar Coop-Phane are still only 20 and 24, so it’s difficult to know now if they are going to last like Victor Hugo, but I take pride in giving them a chance, and I think that’s the role of the Flore. The prize has two goals: one is to get drunk on the night of the party, and this part is really a success. The Café de Flore is transformed into a nightclub and we had Justice – you know the DJ electro band? – who played music on the night… and anyway, apart from this, the second goal is to reveal young talent.

MR: As part of their prize, winners are entitled to a glass of Pouilly Fumé at the Flore every day for a year. Have any of the winners come close to claiming this?

FB: Yes, I think Vincent Ravalec drank almost every day. Houellebecq asked if he could drink the 365 glasses in one night, but he was refused.

I want to be Don Draper, I want to live in this magical world of the sixties and seventies where you could read magazines with boobs on one page and a politician or a very clever philosopher on the next.”

MR: One of your next projects is to head up the relaunch of Lui magazine in September, which you’ve said will be a ‘hedonistic anti-crisis magazine’ published as ‘a gesture of disobedience’, which sounds like fun. Will it replicate the old magazine’s formula of highbrow literature and soft porn?

FB: Exactly, that’s the idea. It’s like in A French Novel, I want to relive the sixties of my parents. I want to be Don Draper, I want to live in this magical world of the sixties and seventies where you could read magazines with boobs on one page and a politician or a very clever philosopher on the next.

MR: We tend to separate them in this country. We publish Playboy but without the literature.

FB: I think literature is a very good excuse to buy Playboy or Lui. So we use an intellectual alibi to show naked women, this is my concept.

MR: So you’re not looking to modernise it at all.

FB: Not at all. Well maybe a little, but you will see.

MR: It’s four years since A French Novel came out in France. What book projects have you been working on since? And is it a little odd to still be talking about this book and the events it portrays from such a distance?

FB: Yes it’s a little bit odd, I agree. But the thing is I haven’t changed my point of view regarding questions about the novel. Why do we want to read novels today? It’s my obsession. Because I work, as you said, in cinema, magazines, and also I’m a TV host and I like to be a DJ sometimes at parties, so I’m not really a normal writer, and I always ask myself what novels can do, and why would someone young go and read a book instead of all these other temptations. So that’s what I’m writing about now. I don’t want to say too much because if I do I will be lazy and I won’t write it, but this question I think is very important because we are now in a time where it’s possible that books will disappear completely, and people may not read novels anymore because there are so many other stories. If you want to see a story, you don’t have to read it. So it’s important that novelists ask themselves how they can survive.

MR: Will Fourth Estate publish the next book?

FB: Yes, but everybody will get fired right after. If they publish the next one, the company will completely close down. So we are discussing that now, and they are a little bit afraid.

* Naturally, this interview is also ‘fictionalised’, to the extent that if a precise transcript of our recorded conversation were reproduced, stumbles and repetitions included, parts would be more or less unreadable. Writing an autobiography from pure memory must by definition be more unreliable. Such observations are reinforced by the fact that they did not occur during our conversation, but only when writing it down. MR

Frédéric Beigbeder was born in 1965 and lives in Paris and Guéthary. He works as a publisher, literary critic and broadcaster. He is the author of numerous novels, including 99 Francs (published in English as £9.99) and Windows on the World, which won the 2005 Independent Foreign Fiction Prize. A French Novel is published by Fourth Estate in hardback and eBook. Read more.

Frédéric Beigbeder was born in 1965 and lives in Paris and Guéthary. He works as a publisher, literary critic and broadcaster. He is the author of numerous novels, including 99 Francs (published in English as £9.99) and Windows on the World, which won the 2005 Independent Foreign Fiction Prize. A French Novel is published by Fourth Estate in hardback and eBook. Read more.

Watch the trailer for Love Lasts Three Years.

Mark Reynolds is a freelance editor and writer and a co-founder of Bookanista.