The ghosts within

by Dinah JefferiesAs my father drove my mother to the nursing home in Malacca, Malaya, their car came under heavy fire. Two weeks later, on August 16th 1948, I was born. Two months before that, in June, three British rubber-planters were shot dead by men arriving on bicycles, thus inflaming tensions that resulted in a state of emergency being declared. The war waged by the British administration against the Chinese MNLA communists hidden in the depths of the Malayan jungles had begun.

My father and mother were newly married, and he’d taken a job organising the restoration of postal services destroyed during the Japanese occupation in World War Two. And so I grew up in Malaya in the 1950s, with giant spiders in our bathroom, snakes in the garden, and birds singing in bamboo cages.

Years later I was living at the top of a mountain in a fairly remote part of Spain with my husband and our large Bouvier when the economic crisis of 2008 happened. We lost nearly everything in the crash. Awful though it was, the impact proved to be the trigger I needed to begin the novel I had been thinking about. Though my first book turned out to be more of a learning experience than a successful novel, it did, however, attract the interest of the woman who eventually became my agent.

While I was casting round for ideas for a second book, I happened to be with my mother poring over her old photograph albums from our time in Malaya. Palm-lined beaches, houses on stilts, and fascinating Chinese markets contrasted with images of the cocktail hour and seemingly endless fancy-dress parties. It felt far removed from the 21st century and I began to wonder if I might be able to use our time in Malaya as inspiration.

While my childhood and the photographs in the family albums portrayed sunshine and happy smiling people, that wasn’t the whole story. There were constant ambushes, regular shootings, and terrifying explosions when grenades were thrown into crowded places. When I set about researching the Malayan Emergency and the country’s colonial past, I didn’t expect to become so completely drawn into what had happened there. In fact I became fascinated not just by Malaya, but other societies also on the brink of collapse, usually when there was political unrest or war, and when all the normal supports were fragile or already destroyed.

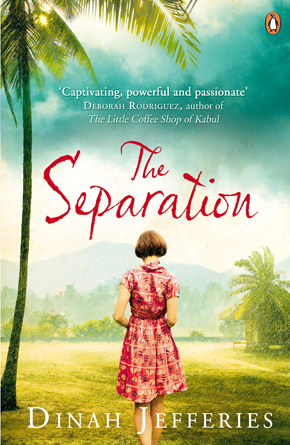

The novel is about the thread between a mother and her child that can never be broken. Lydia, the mother, returns home to find her house in Malacca is empty and her daughters are missing, with no explanation where they’ve gone. Unbeknown to Lydia, the children Emma and Fleur have been taken by their father to live in England, also with no explanation given.

From the stories my mother told I knew that at that time in Malaya not many colonial wives worked, and few were fortunate enough to have financial independence. As I conceived the character of Lydia, I saw her as a woman who suddenly finds herself alone and stranded in a dangerous environment, with no money and no job. Her voice came easily. She would be a bright, talented woman who adores her children, but who is trapped in a loveless marriage and needing more from life. In the 1950s many women were not able to pursue their dreams or develop their talents, and as I had been a teenager in the 1960s, a decade that was to be the complete opposite of its predecessor, I had sympathy for the typical middle-class 1950s woman who didn’t have my chances. Lydia is a flawed character in many ways, but she’s also brave and warm, and she refuses to quit as she battles the odds to find her children, especially when she’s sent on a wild goose chase.

In post-war Malaya everything was in total disarray, which would make it difficult for her to trace her missing children, and the dangers of the Emergency itself would make her search yet more fraught.

The structure was decided when I chose to alternate chapters between Lydia and her elder daughter Emma. Emma is a livewire and she gave me a wonderful opportunity to delve into the past again. She isn’t me, but she did spring from my childhood memories. I gave her some of my experiences and I even use a scene I witnessed myself:

Mother didn’t know that I’d seen even worse at the waxwork museum. Just past the shrunken heads, there was a Children Prohibited section. I didn’t stay. Only long enough to see tiny figures of white women and children, pinned to the ground, still alive, their painted red mouths wide open in a scream. Coming towards them, driven by a Jap, was an enormous steamroller, normally used to flatten tarmac roads. Only this time it was being used to flatten those people.

In part the novel is an exploration of love and loss, which meant that I had no choice but to draw on the experience of losing my own son to write Lydia’s story. It was a difficult period of my life to revisit, and harrowing to do, but it was necessary and, in some ways, cathartic. To create Emma I recalled the experience of leaving my childhood home in Malaya to come to live in cold, wet, grey England, made worse for Emma because her taciturn father will not tell her why they have left their mother behind. I also chose to lend Emma my own feelings of desolation and alienation when I arrived in England. We docked in February, as she does, and like her I missed Malaya and didn’t fit in.

Now people ask how it feels to be a debut novelist at the age of sixty-five. Well it feels great, of course, and it feels surprising, and I’m very happy, but other than that it’s probably much the same whatever age you are. Perhaps I have to write more quickly, I don’t have as much time to waste, my energy isn’t the same as it once was, and I can’t wear killer heels for my launch party! What I do have is a depth of memory and experience to draw on and dozens of ideas in my head.

Since setting The Separation in Malaya, I’ve also fallen in love with Sri Lanka and Vietnam. My next book The Tea Planter’s Wife will be published by Penguin in 2015, and also internationally. It’s set in Ceylon between 1925 and 1934, a colonial country poised just at the point before everything is set to change. Here the central female character is torn apart by a complex and frightening situation.

Although The Separation is fictional, people also ask how much of my own life it reflects and what my influences are. I think of this: “All fiction is largely autobiographical and much autobiography is, of course, fiction.” – P.D. James. There is a kind of alchemy that happens when you draw on life experience and transform it into something different. I don’t believe the thought processes are necessarily conscious, yet parts of my life live like ghosts within the pages of The Separation.

Several books I’ve loved have also influenced me. Classics like Jane Eyre, the novels of Thomas Hardy and Daphne du Maurier, and more recently Julia Gregson and Rosie Thomas. If a novel has a vivid narrative that bring the characters to life it will appeal to me. I like books and films that make me think: often subtitled films. But more importantly, I enjoy works that make me feel. That’s what I aim to do in my own writing. I like to sit on a character’s shoulder, in order to see through their eyes and discover how they feel when life goes wrong. I set my books in the 20th century because I was around for quite a large part of it. Packed with such incredible changes, it is an amazing period to write about, though the dramas that my characters face, and the emotional consequences they experience, are timeless.

When we arrived in England at the Liverpool docks on that grey February day in 1957 the shutter came down on our Malayan lives. It was a loss, as it is for Emma, but since writing The Separation I feel more connected to that faraway childhood I left behind. Writing the novel and revisiting the scenes of my childhood allowed me to slip back in time. It helped me remember where I had come from, and when you know where you come from, you feel better about being where you are now. I think it was a book I had to write, and now I can move on to write more, indeed I already have. It may have taken me until my sixties to discover the thing I love to do more than any other, but I’m just grateful that although our car came under fire as my father drove my mother to the hospital to give birth to me, we were lucky. It might have been a very different story.

The Separation is published by Penguin in paperback and eBook. Read more.

dinahjefferies.com