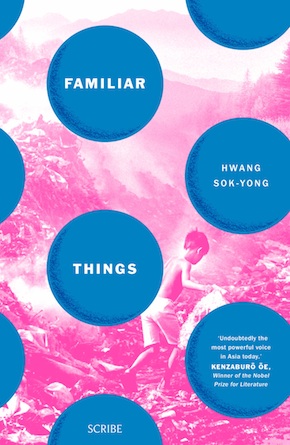

A dream of good fortune

by Mika Provata-Carlone“When he’d heard the name ‘Flower Island’, he thought they were going to some paradise overlooking the ocean” – with not much more than these words, a thirteen-year old and his mother must choose between a life of increasing impoverishment and a promised alternative of redeeming ‘enoughness’. The choice seems obvious, and in Familiar Things Hwang Sok-yong creates a darkly lyrical epic out of the most unlikely and most grippingly raw human material. Using a stringently narrow focus, cropped frames and almost non-existent horizons, Hwang Sok-yong’s talent lies in his particularly powerful, understated narration, where both the register of perception and the scope of understanding seem dramatically reduced to the most elemental state – pleading, evocative verbatim fiction that replaces self-reflexivity or direct commentary, allowing for a very moving suspension of disbelief and of critical distancing.

The paradise of Flower Island is a vast lunar landscape of landfills, where a shadow-world of families live in order to process very precisely and methodically everything the real world considers the trash, filth, unwanted scraps and dregs of the highly modernised and ambitious existence of a neighbouring megalopolis. This alternative universe of throbbing non-being reproduces with chilling deliberation the hierarchies, desires, vices and dreams of the world they can no longer go back to. At the same time, the resignation to subsist (“people live there like anywhere else”) walks hand-in-hand with an almost transcendental sense of enchantment: the place of nothingness is more capable of yearning for a sense of value and worth than the city of everything that seems in a constant state of dissatisfied gluttony. “The garbage was dirty and ugly, but it was also black and white and red and blue and yellow and iridescent and shiny, and it was smooth and square and angular and round and long and limp and stiff, and it refused to budge and it sprang out of the pile and it rolled down the slope, and it smelled acrid and it smelled foul, and it made your breath catch and your nose run and it made you gag, but above all, none of it looked familiar.” There is desperate yet earnest marvel and fascination in a slab of vinyl flooring, a shred of fabric, an expired bag of defrosted frozen rice, the promise of treasure in a soiled cast-off or dented tarnished pot, the dream of a feast at the sight of the spoils from a food market’s waste skip.

Unlikely friendships will inspire what Hwang Sok-yong has said he values most highly: a sense of empathy, a gaze that does not flinch but recognises and invites.”

There is a sense of disturbing abandonment that could have stopped at the level of a prison-camp state, a Victorian slum drama, a dystopia of very physical haunting horror, yet the very real beauty of Familiar Things resides in the act of transfiguration that happens in the very midst of the desolating non-entity that it depicts. The predicament of a mother and son becomes a very unique journey of self-discovery, a quest for a sense of personal and national identity, for values that will replace a damaged social fibre, alienation and material detachment, state extremism or a political vacuum. Everyday gestures of an almost atavistic existence become rites of passage, an initiation to a different possible reality for the characters throughout, and especially for those few who survive a harrowing fire that ravages the landfill, brutally claiming lives and exposing the sinister inconspicuousness of that entire community in the eyes of public conscience and state obligations.

Unlikely friendships will inspire what Hwang Sok-yong has said he values most highly: a sense of empathy, a gaze that does not flinch but recognises and invites. He creates through a finely balanced juxtaposition of harsh, raw realism and an almost poetical vision an impetus to know the fate, the inner soul, the bare minutiae of the lives of his characters. “The act of writing must be a political act,” he has insisted, “my ethos as a writer means that I must be engaged, that is to say interested in the life of others, I must seek to bring about the evolution of society.” And so he favours contradictions, jarring double exposures between a world of affluent modernity and its shadows, but also between a global society and a traditional culture that provided meaning, relationships, a faith in and a vision of humanity. Hwang Sok-yong uses margins and marginalisation to reveal the vital core of things, and his novels evoke worlds not only of extreme circumstances but also hidden worlds of mystery and lost beauty. Shamanism, a supernatural reality, the myths and legends of Korea are constant elements of his fiction, as are the loss of a place, symbolic or real, the loss of a sense of self or even of a legitimate presence and being.

He is keen to explore the underlying traumas of Korean self-perception and historical potential, not only in the division between south and north, in the weighted dynamics of Korea’s past relations with China and Japan, and the multiple stages of occupation and dispossession, but especially in the moment of identity awareness that could have been the meeting between the Korean mind and culture and the West, the transition to modernity which was instead traumatic, an externally imposed process of colonisation, deculturalisation and ruthless mediation and urban progress that left deep marks. In Flower Island Hwang Sok-yong conjures up a very tactile, fragile world, where abuse and gentleness coexist in fearsome tension. His characters are drawn almost calligraphically, some remain unchanged, providing the context of reflection, some undergo the most fundamental transformations. These will be the ones to recover by the end of the novel not only presence, attachment, a sense of direction, but also long-forgotten names instead of humiliating nicknames, a purpose not only for themselves, but especially for others as well. Bugeye will become again Choi Jeong-ho thanks to an unexpected ‘brother’ he acquires, a younger boy very much reminiscent of a Shakespearean fool – a sprite-like outsider full of wisdom, laughter, cunning insight into the true reality of things, and a tragic destiny. ‘Baldspot’ (so called because of multiple childhood abuse) will guide Bugeye to an old man and his epileptic daughter who rescues thrown-away pets. She in turn will lead them to the twilight realm of Flower Island, the world of the dokkaebi, in this case kindly spirits considered as guardians, the lingering souls of layers upon layers of previous lives in an unmodernised Korean past. Bugeye and Baldspot will revive a sense of elemental community, discovering enchantment in gradual rehumanisation – the retrieval of names follows a very long bath and the purchase of new clothes, the reliving of the memory of a neighbourhood and of social belonging; the dream of escape is replaced by the longing for love, the adventure of money that can satisfy innocent, childish dreams, especially by the will of reconstruction, of safeguarding this surreal world of spirits and men from further adulteration.

It is hauntingly poetical, delicately philosophical, unyielding in its urging to use the past to rescue a present heading for self-destruction.”

Hwang Sok-yong’s stripping down to essentials lends brittle, yet genuine grace and beauty to all that we would rather ignore. He crafts light out of darkness, lament instead of anger and rage, naked humanity in his hands is given the garments of its truest dignity: compassion, community, a love for life and an instinctive urge for beauty. In Flower Island Hwang Sok-yong does not create echoes of a wider historical or political perspective of Korea. He has done so in other novels, as in his self-admittedly autobiographical The Star of the Dog Who Awaits His Dinner, that was recently translated into French. Familiar Things reworks the material of his short story ‘A Dream of Good Fortune’ (1975), and is a reimagined realist narrative which, as he has said, provides “a way beyond the division that the ‘I’ creates and towards the universality of the world.” It is hauntingly poetical, delicately philosophical, unyielding in its urging to use the past to rescue a present heading for self-destruction. Sora Kim-Russell’s translation is sometimes uneven, awkwardly and artificially argotic at the expense of the more natural rhythms a French reader would hear in Hwang Sok-yong’s text. Nonetheless, the overall voice that emanates from Familiar Things is truly hypnotic, possessing clarity of truth and a sense of purity that is not to be missed. Hwang Sok-yong has been hailed as one of the most poignant voices in East Asian literature, and Familiar Things evinces the power and the resonance that he deserves to have with an English audience.

Hwang Sok-yong is a recipient of Korea’s highest literary prizes, whose novels and short stories are published internationally. Previous novels include The Ancient Garden, The Story of Mister Han, The Guest, The Shadow of Arms and Princess Bari. Familiar Things is out now in paperback and eBook from Scribe. Read more.

Hwang Sok-yong is a recipient of Korea’s highest literary prizes, whose novels and short stories are published internationally. Previous novels include The Ancient Garden, The Story of Mister Han, The Guest, The Shadow of Arms and Princess Bari. Familiar Things is out now in paperback and eBook from Scribe. Read more.

Author portrait © Philippe Lissac

Sora Kim-Russell’s previous translations include Hwang Sok-yong’s Princess Bari and Gong Ji-young’s Our Happy Time.

sorakimrussell.com

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.