Grace Paley: ‘Goodbye and Good Luck’

by Sean LuskI was fortunate enough to see Grace Paley speak. It was back in 2003 or thereabouts at the Small Wonder Festival at Charleston. I think it might have been the first time the festival, which celebrates the wonder of short stories (the clue’s in the title), had taken place. Grace Paley had been due to come in person, but ill health prevented her from making the journey from New York, and so Ali Smith interviewed her (brilliantly) via a video link. We’re all used to Zoom nowadays, but back then Zoom didn’t exist, and satellite links were shaky. Yet Paley’s energy, her anger at every injustice, her humour, her warmth, and her sheer stubborn belief in the human spirit came across as if she’d been right there in that Sussex barn with us.

‘Goodbye and Good Luck’ is the opening story in her collection The Little Disturbances of Man, its publication in 1959 the result of what she characteristically described as “two small lucks”. The first of those lucks was an illness which meant she couldn’t care for her children full-time, giving her more time to write. The second was that an editor at Doubleday (the ex-husband of a friend of hers) read three of her stories and commissioned her to write some more. If this makes Grace Paley sound in any way passive in the process then I’m misleading you: Paley was a vigorous pacifist and feminist, and those causes were her priority all her life; she fought hard, often struggled financially, and was brave and uncompromising.

‘Goodbye and Good Luck’ is an important story in so many ways – for its voice, for its compassion, for its humour and for the way it introduces us to the whole body of Paley’s work. Every single story of hers is a masterclass in writing. Here are the opening two lines:

I was popular in certain circles, says Aunt Rose. I wasn’t no thinner then, only more stationary in the flesh.

We ‘get’ the voice immediately: New York Jewish, funny, self-aware, unashamed. There’s a music, a certain recognisable beat to Aunt Rose’s voice throughout the story which is absolutely authentic. Paley had an ear, and an ear is all a writer really needs when it comes to dialogue, because the way people talk on trains and buses and in cafes is how people really talk, and good writing makes sure that’s the way people talk in stories too.

Paley made careful decisions about story structure. In ‘Goodbye and Good Luck’ Aunt Rose addresses her niece, Lillie, but Lillie has no dialogue, and barely any presence at all in the story. We are addressed directly by Rose not as readers but as if we the readers are Lillie, and as a result we are made powerfully aware of Rose’s character – her pride, her vulnerability and her chutzpah. It is a conversation we are part of, so much so that we begin to feel a little awkward, wishing Rose wouldn’t give so much of herself away to us, which is part of the story’s genius.

Rose at first seems an unreliable narrator, as she tells us of her affair with the much older actor Vlashkin, who eventually rents an apartment for Rose.

Vlashkin helped me to get a reasonable room near the theatre to be more free. Also my outstanding friend would have a place to recline away from the noise of the dressing rooms.

But, having lulled us into thinking of Rose as naïve, we then see her assert herself when she meets Vlashkin’s wife.

She noticed me like she noticed everybody, cold like Christmas morning… Poor woman, she didn’t know I was on the same stage as her. The poison I was to her role, she did not know.

After this Rose kicks Vlashkin out of her apartment and out of her life.

The dialogue (in fact monologue, since it is all delivered through Rose) is unfailingly funny. After Rose parts with Vlashkin she is subjected by her mother and grandmother to a succession of suitors.

Another fellow: Yonkel Gurstein, a regular sport, dressed to kill, with such an excitable nature. In those days – it looks to me like yesterday – the youngest girls wore undergarments like Battle Creek, Michigan. To him it was a matter of seconds. Where did he practice, a Jewish boy? Nowadays I suppose it is easier. Lillie? My goodness. I ain’t asking you nothing – touchy, touchy…

In this passage we come to understand that Rose is worldly-wise, and maybe it is Lillie who is innocent. This is also one of the few times Lillie is acknowledged explicitly in the story.

Finally, there are the rhythms of the story. The title ‘Goodbye and Good Luck’ is repeated three times. First in the passage where Rose, having been insulted by her mother (Lillie’s grandmother) for moving in with Vlashkin, tells Lillie about her mother’s relationship with her father:

She married who she didn’t like, a sick man, his spirit already swallowed up by God. He never washed. He had an unhappy smell. His teeth fell out, his hair disappeared, he got smaller, shrivelled up little by little, till goodbye and good luck, he was gone…

The second time is when Rose throws out Vlashkin. And the third is the story’s big surprise, for at its ending, after we assume all along that Rose’s life is a proud tragedy, we stumble upon a happy ending.

So now darling Lillie, tell this story to your mama from your young mouth. She don’t listen to a word from me. She only screams, ‘I’ll faint, I’ll faint.’ Tell her after all I’ll have a husband, which as everybody knows, a woman should have at least one before the end of the story… tell her from Aunt Rose, goodbye and good luck.

That husband is old Vlashkin, now divorced from his wife. But no matter.

It’s really not possible to tell the story – any story – by describing it. You will have to read it for yourself. It won’t take you long. And it will last you maybe a lifetime. Goodbye and good luck.

“One of the best books I’ve read this year. Atmospheric, engaging and elegantly written… completely unforgettable.” Bonnie Garmus

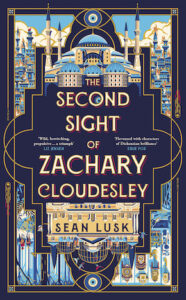

Sean Lusk is a winner of the Manchester Fiction Prize, the Fish Short Story Prize and the Cambridge Short Story Prize, and a runner-up in the Bridport Short Story Prize and the ALCS Tom-Gallon Trust Award. His debut novel, The Second Sight of Zachary Cloudesley, is published by Doubleday and Transworld Digital in hardback, eBook and audio download.

Read more

seanlusk.com

@seanlusk1

@DoubledayUK

@TransworldBooks

Grace Paley (1922–2007) was a renowned, Bronx-born writer and activist. Her Collected Stories (1994) was a finalist for both the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award, and is now published in Virago Modern Classics, introduced by George Saunders. Her other collections include Enormous Changes at the Last Minute and Just As I Thought.

Read more

@ViragoBooks