A happy nation

by Agnieszka Dale

“Dale is between cultures, rooted in one, integrated into another… She knows what makes us laugh, and what makes us laughable.” Jeremy Hardy

I don’t believe this is an emergency for Great Britain, officer. It’s just a crisis, you know, a little crisis. See, in an emergency, you call the ambulance. You call the police. But a political crisis is different. It’s just an inconvenience.

So you can relax, really. Fully. Entirely. Relax. You can even fall sleep. The world won’t see. And no, you haven’t woken me up. Please, do come in. I was wide awake anyway. I just couldn’t sleep. I had an awful nightmare which woke me up. I was expecting you, really.

How is it, this present crisis, officer? How is it for you? Empty streets, shops closing down, and all the immigrants gone away, as if on holidays; as if it was August. All of them but me. The only one now refusing to leave. Yes, I know, Polish immigrants were less than two percent of the population but it does feel a little empty without them. No? Not for you? Well, I guess I am still here. You all know me, Krystyna Kowalska.

You are doing your job. I understand. It’s all right. You all seem so innocent, you, immigration officers. Like history never touched you. And please, do sit down. You don’t have to stand up to interrogate me.

You are just too nice. You like me, don’t you? That’s the problem. You like me a lot.

But how are you feeling? Because, you know, I am fine. I am always fine. But you? Have you been unhappy these last few years, with me, just me, left? With this isolation? Have you tried calling anyone? Does it feel like you are always unhappy or only sometimes? Every holiday you now go to Wales. And if you were Welsh, well, you’d have nowhere to go. Are you quite happy now, where you are standing? I can’t quite see you with this light in my eyes.

No, you are not upsetting me by asking me for my ID. Not at all. Although you ought to know who I am by now. I am used to having my ID checked. At home, in Poland, we all have IDs, many IDs. But I still love it here, with ID, or no ID, I feel loved, just loved by everyone: neighbours, colleagues, shopkeepers, and maybe that’s why I’ve been refusing to leave. Because I am just a happy person, every day, even if I go through immigration checks, every day, or when I am searched on the street, or interrogated in the middle of the night, like now, I like it here. I am still happy and there is nothing you can do to upset me. Not really. Because you are also so nice, so kind. But please, like always, let’s talk first. Let’s talk, before the interrogation starts. I like small talk. Do you?

Are you looking at this pink teddy? It makes me so happy! Christmas present from my father, when I was six. I lived in Gdańsk. Tanks encircled Poland then. I was lucky not to see them but I could feel them, like a rope on a throat. Or more like snow, which never stops snowing, and covers everyone and everything, until you can’t breathe.

Yes, this is my father. Yes, that’s right. He does resemble Lech Wałęsa. Wałęsa made me happy, too. He spoke to us like a fearless poet. We all believed him because he had faith. He was fearful only of his wife. It made me happy when he spoke, when he said, “Let’s do it.” And so history became a Nike advert from the future; a sport you played – like hockey – with your own history stick.

My grandmother was one hundred percent whitish, as I see it now. Three-quarter Polish and one-quarter something else, undetectable now of course.”

And yes, I still play with Barbies. I really do. I won this one in a rope-skipping competition. Nobody had Barbies in Poland then. Not very many people. It felt like I was the first. The first little girl with a Barbie. General Jaruzelski imposed martial law on me and my Barbie. But martial law made me happy because the tanks didn’t come. Not many. They stopped. And it stopped snowing. And sometimes, because of the curfew, we would stay in friends’ houses for sleepovers. Lots and lots of sleepovers. They made me happy. The growing solidarity in everybody’s bedrooms. Baby-boom time. The Wałęsa and Jaruzelski time. Jaruzelski, our last communist leader. The benevolent dictator. The man behind the Round Table Talks, which made me happy because I saw political enemies sitting at one table, talking, discussing the future, arguing, exchanging different opinions, but never leaving the table, for three months. Perhaps we could have tried that here. Oh, happy times!

We still have time, don’t we? You’re not in a rush are you? So let me tell you what else made me happy. The Berlin Wall, oh yes, the Berlin Wall. Or rather, us jumping into little Fiats and driving all the way from northern Poland to Berlin, for over twenty hours; big families in their little Fiats, all driving just to see the Wall, the falling Wall. Soon after, Sebastian – who was half-Russian and half-Czech – asked me out to see Gremlins 2.

Then, a long kiss on the school bus, with a German exchange student called Hans. Hans was not a great kisser – he just wasn’t, officer – but even he made me happy. And I was scared to tell my grandmother. She was one hundred percent whitish, as I see it now. Three-quarter Polish and one-quarter something else, undetectable now of course.

Yes, whitish, you heard that right, officer. The White Other category, in other words. Before your time, perhaps? So let me explain.

Whitish used to be an ethnic group in the UK Census: it described people who, no, were not British, but who self-identified as white persons. This meant that the White Other group contained a diverse collection of people of non-British birth, religions and languages.

Oh, are you sleepy officer? Are you looking at this picture? My grandmother. Beautiful, wasn’t she? She had no British blood in her, not even a drop. She only spoke Polish, except for a few Russian swear words, which can have an influence on the purity of one’s blood, as you know. Her great-grandfather came from Vienna so she could also be a little Austrian, German, Slovenian, Romanian, Jewish or even Italian. But she said she was happy, very happy that we had these exchanges in schools, so soon. That I could kiss a German.

“But who else, Krystyna?” she asked. “Who else do you want to date? How about a British man?”

“A British man, Babcia?” I wasn’t so sure.

Yes, let’s have a glass of wine. Thank you. Glad you found it in the fridge. Good idea. Before we start. I can warm up pierogi for us if you like? How would you define “British,” officer? Do you know who you are? Did you learn about Great Britain in your history classes? The history of colonisation? Oh, you only learned about crop rotation and the Middle Ages, and then skipped to World War I?

Oh, I like the British. You all wear hats, like you, officer. And even if you don’t wear one, it feels to us immigrants as if you did. You know, even in bed, you wear invisible hats which make you look so distinguished. A person, in a hat, must be right.

Why am I here, you ask? You want to start? Is this your first question? I’m sure I’ve told you before. Can I still sip my wine, please? I came to Great Britain to mix my blood. This was my only reason, which I gave to the border control guard. Not the benefits, not the work possibilities, I said to him, but sexual intercourses with a Brit.

“Just the one Brit?” he double-checked.

“Yeah,” I answered. “One Brit. I met him in Poland, on another school exchange. He’s British. But he is actually one-fifth Spanish. And a little Irish. Or just from Liverpool.”

He yawned, just like you, just then, a minute ago, and he let me in.

What? You don’t have that option in your form? You don’t have sex? Sorry. Just tick “other reasons.”

From the delivery room at St Thomas’s Hospital, while pushing out my baby, everything seemed perfect, in every way. Childbearing made me very happy because I had a great view despite the great pain.”

Later that year, Great Britain opened its borders to Polish people. And the enlargement happened just sort of naturally. With no protection, you might say now. Absolutely none.

Yes, these are my children. As babies. Fresh from the hospital. Nice pictures, aren’t they?

From the delivery room at St Thomas’s Hospital, while pushing out my baby, everything seemed perfect, in every way. Childbearing made me very happy because I had a great view despite the great pain: the Houses of Parliament.

Ah, like a baby. You must be tired, officer. I’ll just tell you a quick bedtime story now before you wake up. Isn’t it funny that I look like you? You must be British. White British.

So what is the difference between us?

Don’t you say that if you look like a duck, swim like a duck, and quack like a duck, then you are a duck? Even if you are not? I know, I know. You don’t like our Delikatesy. Not so much the sausages and the bread but more the design of the shop signs. The fonts we use. You hate Arial, all in caps, too, and red and white is just not a good colour combination, design-wise. I know, I know, you need a third colour for better branding, like the French but we only have two. Yes, you can tell we don’t study art and design in schools the way you do in Great Britain. And your signs are great. But how come you don’t mind the Indian corner shops any more, or the Jamaican fruit and vegetable market on a Monday morning? Or Chinatown? Why us? Why me?

But I don’t think it’s all about appearances, really, our shade of white – eggshell or potato – only clear to you if we open our mouths. But what if we stay silent, or suddenly speak just like you? We could pass for indigenous Brits, couldn’t we? After all, isn’t the Queen a little German, and even a little Polish? And can you tell, by the way she speaks?

I can speak English like a British person now. And that’s exactly why you want me go, isn’t it? Because you’ve lost control. You can no longer tell me from the others. White others. I could be white other, or I could just be white. The great white. You’ll never know. I’ve assimilated in everything: education, sense of humour, style, and now also my speech. So I am a threat. Because what if I am actually a little better than you. Not much, just a little. A little cleverer. Funnier. Prettier. More organised. Not much. Just that tiny bit. Yes, it must feel like I am keeping you on your toes. I can’t help it. It’s just the way I am. But you need to develop too. You need to meet me half way. I need to teach you manners maybe. My manners which are about telling the truth and facing the truth, in order to become greater than great. Which you don’t see just yet, you don’t see that process, and you perhaps never will; you can’t. Besides, it’s too late. I am leaving. Finally. Because I am a bit worried, just a little bit worried about the gun I see poorly hidden under your nice jacket. You’ve never brought a gun to my house before. I am just worried that when I stop talking to you, you will start talking to me more and more, and then I don’t know what you will say. So I just want to remember you as a nice person who said nothing, nothing much. Someone nice who came here now and again, listened to me and never caused me any harm.

Besides, the views from the train will be good, still good. I might stop in Normandy for a day, just for a little dip in the nice sea, or just for a modest beer somewhere in Germany, which is a nice country, too, with some nice designs of beer labels. Then, I will travel across Poland and then Ukraine. Then, deep into nice Russia, until it becomes nice China. I’ll order a take-away and I’ll sit by the embankment thinking of how it reminds me of London, that part of Shanghai, its design, and of all things great, which somehow got diluted by all this niceness, especially the fine dumplings from Shanghai, dumplings which taste as if they could be Polish or Ukrainian or Japanese but happen to be Chinese, of a Shanghai variety, and nice, very nice. Lots of happy dumplings, still here and there. Pretty much everywhere, really.

So where is my passport? Where is my ID?

These are nice pockets, officer. Soft to touch, like the belly of my pink teddy. And your ID card is here too, next to mine. Let me see. Adam. That’s a nice name. Adam Michalowski, born in Lambeth, White British. You have always seemed nice.

So wakey, wakey, Mr Michalowski. Please, do let me out.

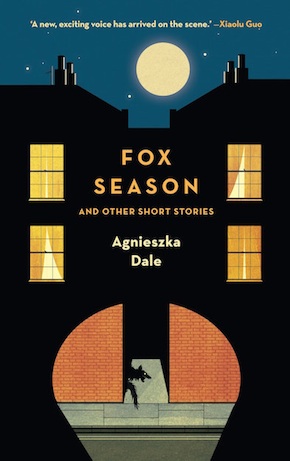

From the collection Fox Season and Other Short Stories (Jantar Publishing, £8.99)

Agnieszka Dale (née Surażyńska) is a Polish-born London-based author conceived in Chile. Her short stories, feature articles, poems and song lyrics have been selected for Tales of the Decongested, The Fine Line Short Story Collection, Liars’ League London, BBC Radio 3’s In Tune Live from Tate Modern, and the Stylist website. In 2013 she was awarded the Arts Council England TLC Free Reads Award. Her story ‘The Afterlife of Trees’ was shortlisted for the 2014 Carve Magazine Esoteric Short Story Contest and longlisted for the Fish Short Story Prize 2014. Fox Season and Other Short Stories is out now in paperback from Jantar Publishing. The title story and a version of ‘A Happy Nation’ were broadcast on BBC Radio 4 in 2015 and 2016.

Agnieszka Dale (née Surażyńska) is a Polish-born London-based author conceived in Chile. Her short stories, feature articles, poems and song lyrics have been selected for Tales of the Decongested, The Fine Line Short Story Collection, Liars’ League London, BBC Radio 3’s In Tune Live from Tate Modern, and the Stylist website. In 2013 she was awarded the Arts Council England TLC Free Reads Award. Her story ‘The Afterlife of Trees’ was shortlisted for the 2014 Carve Magazine Esoteric Short Story Contest and longlisted for the Fish Short Story Prize 2014. Fox Season and Other Short Stories is out now in paperback from Jantar Publishing. The title story and a version of ‘A Happy Nation’ were broadcast on BBC Radio 4 in 2015 and 2016.

Read more

agnieszkadale.tumblr.com

@AgnieszkaDale

Author portrait © Rebecca Pierce