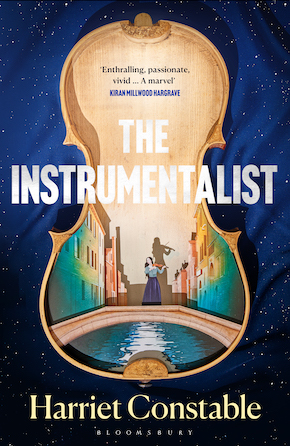

Harriet Constable: The Instrumentalist

by Farhana Gani

In 1696 a baby was posted through the wall of the Ospedale della Pietà, an orphanage in Venice. She was named Anna Maria della Pietà and become one of the greatest violinists of the eighteenth century. Her teacher was Antonio Vivaldi…

YET THIS EXTRAORDINARY MUSICIAN remains largely unknown today. Numerous historical records exist – she dazzled Catherine the Great, won acclaim from the elite and critics alike, and even inspired Rousseau and Casanova. Vivaldi himself owed much of his success to her. So how did this musical prodigy, once the toast of Europe’s music scene, vanish into obscurity?

Enter Harriet Constable, journalist and documentarian, whose keen eye for a compelling narrative shines in her masterfully crafted debut novel, The Instrumentalist. This meticulously researched historical fiction breathes life into real people and events, plunging readers into the thriving, paradoxical world of Enlightenment-era Venice – a city where the arts reign supreme and orphanages double as elite music academies, to feed the velvet-cloaked and bejewelled’s hunger for the finest music.

The beating heart of the novel is Anna Maria. We follow her journey from abandoned baby to child prodigy as her musical talent blossomed, and finally to her late teens when she became the talk of the town, and her adored mentor Vivaldi’s greatest rival.

There’s a filmic quality to Constable’s prose as she paints a vivid contrast between the convent’s austere confines with the noisy pandemonium of Venice’s chaotic streets, balancing danger and beauty with complex relationships, crafting a biographical narrative as gripping as any thriller.

The novel also unveils the fascinating world of the Ospedale della Pietà and its famed orphan orchestra, the figlie di coro. In this pressure cooker of talent, success is everything and failure spells ruin. Despite harsh discipline, the girls receive world-class musical education, pouring their souls into their art. They play what it means to be a girl in this world. The fame and devastation, the fear and exhilaration, the rush of ideas and the crush of silence.

From the age of eight, Anna Maria knew that her purpose in life was to become the best violinist Venice had ever heard. It wasn’t easy. Her path was fraught with intense practice, fierce rivalries, and a complex protégé-mentor dynamic. Anna Maria’s determination to be the best, no matter the cost, isolated her from most of her peers, and the few close friends she was able to hold on to were often frustrated at taking second place to her violin. Vivaldi, recognising a kindred spirit, nurtured her talent but also exploited it, stoking her ambitions while claiming credit for her genius.

The novel raises uncomfortable questions about Vivaldi’s mentorship. Initially fatherly, his attention turns controlling and hostile as Anna Maria’s confidence grows. He emerges as a manipulative bully, increasingly petulant as jealousy consumes him, even destroying her compositions and bitterly threatening her: “I created you… What did you think? That you, a woman, would be remembered as one of history’s greatest composers?”

Thanks to Constable’s captivating exposé, Anna Maria della Pietà takes centre stage once more, three centuries later. Brava, Maestra!

Harriet tells us more about Anna Maria’s journey from her abandonment as a baby to becoming the greatest violinist of her time, and her intense relationship with her mentor.

Farhana: Can you summarise The Instrumentalist in up to 25 words?

Harriet: A story of ambition, talent and passion based on real-life eighteenth-century Venetian violinist and orphan Anna Maria, the star student of Antonio Vivaldi.

I could find out a lot about Vivaldi but I couldn’t find out how it felt to be Anna Maria. What was it like for her to play, to perform, to create? My solution was to tag the plot to the truth but to imagine into the gaps.”

The characters throughout are brilliantly realised – how did you develop them?

I began by researching in the British Library. I was able to discover some remarkable things about my lead character, Anna Maria, from books and articles. She was Vivaldi’s favourite student. He purchased a violin just for her. She was a child prodigy and went on to eclipse even the great Giuseppe Tartini. I could find out a lot about Vivaldi too – his personality, the technical details of his music and his career. But I couldn’t find out how it felt to be Anna Maria. What was it like for her to play, to perform, to create? My solution was to tag the plot to the truth as much as possible but to imagine into the gaps. I decided I write her story as fiction.

To get a sense of what Anna Maria’s mindset might be I made a horizontal history. I plotted Anna Maria’s timeline next to Antonio Vivaldi’s next to Wolfgang Mozart’s; Venice next to Paris next to London, and so on. I realised that, on the one hand, these were orphan girls at the turn of the eighteenth century and life would have been very difficult for them. But on the other hand, they were given education the likes of which most women would never know. They were allowed to play instruments usually reserved for men. And they were growing up in Venice – the most prosperous place on earth. They would have had an element of confidence because of this. They were hungry to save themselves with music. They were determined and ambitious and resilient beyond belief. In many ways, they were modern women.

What is your relationship with Antonio Vivaldi and his music?

I grew up in a musical family. My mum is a classically trained musician; everyone in my family plays an instrument or two. The music of the greats – Bach, Mozart, Vivaldi – was the soundtrack to my upbringing. But it wasn’t until I discovered that Vivaldi developed much of his music at the Ospedale della Pietà, an orphanage in Venice, that I took a big interest in him and his work personally. With this breeding ground, this test bed of talented women and girl musicians with whom to try out ideas on, a whole new form of music was born: the concerto. Audiences had never heard anything like it. I started listening to The Four Seasons every morning before I began to write. I’d stand in my living room, blasting it out, imagining I was Anna Maria conducting. Then I’d rush to my laptop and begin to type.

Why did you choose to write the novel from Anna Maria’s point of view?

We have spent a very long time hearing about Antonio Vivaldi. And yet behind him were hundreds of remarkable women and girls who were vital to the roots of classical music. Most people have never heard of Anna Maria della Pietà. It was time to hear her side of the story.

Was there a particular event, person or insight that pushed you to write this novel – and how long have you been developing it?

I discovered the story in 2019. I started researching immediately, and by the autumn of 2021 I was spending a few days a week in the British Library. I visited Venice for the first time in January 2022 and started writing my first draft. By October 2022, I had a manuscript ready to share with agents. I have long loved historical fiction, so lots of authors inspired me. But my dear friend Krystal Sutherland was a huge inspiration and encouragement, she’s a New York Times bestselling author of YA fantasy. She welcomed me into her world and she set my mind ticking on the realm of fiction. She told me I belonged here.

Your novel transports the reader to eighteenth-century Venice, the sounds, the smells, the wealth and the poverty. What made this city so desirable at this time?

By the eighteenth century, Venice was the most prosperous place on earth. People were packing up their lives and travelling to the Republic from across the world just to taste the potential. Napoleon came in and ruined everything in 1797 of course. But before then, Venetians had enjoyed centuries of economic and political stability. A government ruled – a mix of monarchy, oligarchy and democracy – rather than a dominant noble family or the church. It gave Venetians the freedom to develop the arts, their industries and their unique political structure like nowhere else on earth.

Tell us about Ospedale della Pieta, the orphanage for baby girls that Anna Maria is ‘lucky’ to be left at, and its famous figlie di Choro.

Infanticide, plague and famine were horribly common in fifteenth and sixteenth century Venice. But because it was also a wealthy and advanced place, Venice’s leaders started developing social welfare systems to deal with these problems. This included taking responsibility for its foundlings.

By the eighteenth century Venice was known as the Republic of Music. Music was constantly present. Orphan boys could be put to work from a young age, but what to do with the large numbers of orphan girls? The Venetians decided to give them a musical education. The Pietà birthed generations of women with musical talent. Women with superstar careers, women who were ambitious and competitive and determined. Women who could not only perform, but create. The figlie di coro – the Pietà’s famous orchestra – became known as the greatest orchestra in Europe.

Was there an equivalent for abandoned boys?

There were boys in the orphanages of Venice. But because they could be put to work from a young age, they were not given musical educations.

The orphanage is a curious place. The Sisters are not motherly, but some are warmer than others, as we see in the different ways Clara and Magdalena interact with the girls. Education is important, especially music, and the music masters are revered, like a religion. There is much money to be made, but the penalties for not making the grade, or keeping your place in the figlie are harsh for the girls. Tell us more.

The Pietà was a remarkable place because it offered girls a musical education. But it was also a tough setting to grow up in. Baby girls would be dropped at the orphanage in the first weeks of their life, passed through a small hole in the wall. If the baby was too big, it would not be allowed in. Many of the girls who grew up at the Pietà suffered serious injuries. There are reports of girls missing eyes, fingers, toes, and those who are scarred from the pox. It must have been a fairly brutal existence.

The colours are the opposite of the darkness – the stark reality that these girls lived on a knife-edge between glory and the abyss.”

Anna Maria is a synesthete, she feels music in colours. Does this explain her genius qualities (or is it more to do with her environment, discipline and determination)?

I wanted to make sure that the music that threads throughout the pages of The Instrumentalist felt vivid and welcoming. That anyone, whether they had a relationship with classical music or not, could enjoy reading about it in my novel. So I gave the notes colours, and Anna Maria the ability to see them rise and move through Venice, to physically tug them to the page.

The colours are also an expression of Anna Maria’s extraordinary mind: she is special, wildly intelligent and creative. And they are a way of expressing that music is the light, the hope, in Anna Maria’s life. The colours are the opposite of the darkness – the stark reality that these girls lived on a knife-edge between glory and the abyss.

Starved of a parent’s love at the orphanage, in her desperation to be the best she becomes ruthless, willingly sacrificing friends when they need her most and keeping fellow players in the figlie at arm’s length. Where did Anna Maria’s drive and independence come from at such a young age?

Anna Maria is utterly determined. She has to be: she is an orphan, and a girl, and it is the eighteenth century. She can either save herself with music, or be put to work, or married off to a man she’s never met. A prodigy does not ‘lose’ at the task of playing their instrument well, because they have a raw, natural talent for their instrument. It is what they were born to do. But they might ‘lose’ in life. Pitted against her friends in this competitive environment, I felt Anna Maria would have to make heartbreaking decisions to achieve all she is capable of.

How do the others react to Anna Maria? She was evidently gifted and destined for greatness. Was there much jealousy?

Anna Maria has two dear friends – Paulina and Agata. She thinks of them more like sisters, they have grown up together. They all dream of becoming great musicians. But these girls are pitted against one another from a young age. There are only so many spots in the figlie di coro, and there is only one soloist position. Not making it is unthinkable. And so naturally tensions and jealousies arise. The question becomes: can they find their way through them and back to one another?

Ambition, talent, trust, fear and sacrifice play a major part in Anna Maria’s story. It’s a power struggle in many ways. How did you go about researching and structuring the novel?

I tagged the plot to as much truth as possible, and then conducted a lot of research to imagine what could have happened in the gaps. Anna Maria was a prodigy violinist known for her skill by eight years old: fact. Antonio Vivaldi bought her a violin: fact. But how did they get to the violin shop? How did she come to be Vivaldi’s favourite student? What did it take for her to get that good? This is where I started inventing.

I used the truth to develop other parts of the plot and structure too. For example, one of the reasons the Pietà existed was because many baby girls were being drowned in the Venetian canals. In the first chapter, this is what almost happens to Anna Maria. Living with the feeling of abandonment, and a fear of water, became a crucial part of the plot.

There are insights into Vivaldi’s own character – his insecurities, his vulnerabilities. Tell us more.

Antonio Vivaldi was an astonishing musician. He had a shock of red hair, and a chest condition that was probably asthma. You can imagine him as this slightly strange looking, slightly weak man. But then he had this intensity and passion for the music. He must have been intriguing, but he was not widely liked. He caused moral uproar among Venetians when he had a young female student move in with him. He died alone and penniless in Vienna, with no idea that 150 years after his death he would be rediscovered, that The Four Seasons would be the most famous piece of classical music in the world today.

Has reverence for musicians changed over the course of history, or was Anna Maria the Taylor Swift of her time?

Anna Maria was absolutely the Taylor Swift of her time. She was a superstar, famous across Europe for her astonishing talent on the violin. We should never have forgotten her.

Why are stories like The Instrumentalist so important in understanding the truth about women in history?

We’re finally getting to know the remarkable women who came before us. We’re finally looking the past through a new lens. It matters that we ask questions of our current version of history; that we explore it from new perspectives. It impacts how we think about ourselves now. And it inspires what we dream of for our futures. History is so much more nuanced, colourful and rich than we have yet imagined it.

Which other hidden women in arts and letters would you particularly love to see recognised?

There are thousands of them! I’m so thrilled to hear Elodie Harper will be bringing us the story of Boudicca’s daughter in her next novel. I’m fascinated by Angelia Kauffman, who was an eighteenth century painter. I adored the exhibition of her works at the Royal Academy and would love to read a novel about her. I’d love to see something about Hypatia, a philosopher and astronomer who lived in the Byzantine era, too.

If The Instrumentalist is to be adapted for screen, do you see it as a TV mini-series or a film?

I think it could be either. I’d love to see it on screen.

Any books you’ve recently read you love to recommend to us, and what are you planning to read over the summer?

I thought In Memoriam by Alice Winn was an astonishing debut. It’s a queer love story set in the First World War. I also loved Briefly, A Delicious Life, a joyous and quirky novel about a long-dead ghost who falls in love with writer George Sand. Tom de Freston’s Strange Bodies was extraordinarily raw and honest. And I’m currently enjoying Disobedient by Elizabeth Fremantle. It’s about the greatest female painter of the Renaissance period, Artemisia Gentileschi.

Finally, what is your own musical background?

I sing and play the piano. I did all my grades on the flute. I grew up going to stage school on the weekends.

—

Harriet Constable is a journalist, filmmaker and author based in London. Her journalism and documentary work has featured in outlets including The New York Times, BBC, Guardian, The Times, Financial Times, NPR and The Economist. She is a graduate of Columbia University’s School of Journalism summer school and is a Pulitzer Center grantee and a fellow of the Royal Society of Arts. The Instrumentalist is published by Bloomsbury in hardback, eBook and audio download.

Read more

harrietconstable.com

@HConstable

@BloomsburyBooks

Author photo by Sophie Davidson

Farhana Gani is a freelance copywriter and book scout for film and TV, and a founding editor of Bookanista.

@farhanagani11

@bookanista

wearebookanista

bookanista.com/author/farhana