High

by Ted McDermottOn a sunny summer weekday afternoon, Ed rode his bike to a head shop called Piece of Mind and bought a one-hitter that looked like a realistic sculpture of a cigarette. Ed was twenty-eight years old and single. He was thin and just over six feet tall. He had dark hair cut short and he wore round wire-rim glasses, cut-off khaki shorts, and a long-sleeved collared shirt. Ed was enrolled in a graduate creative writing program, which meant he taught one section of composition a semester and took workshops and other easy classes, but now he was five weeks into a four-month summer vacation and he had nothing he had to do. He’d been rolling joints for himself, but he thought he’d be able to moderate better how much he smoked if he had a small bowl. He’d never bought a bowl. Never in the seventeen years since he’d started smoking weed, as a sixth grader. Now he had one. Now what?

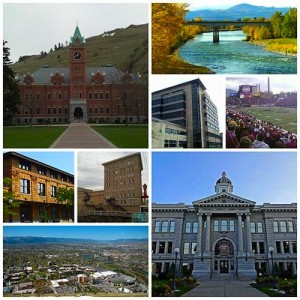

Ed biked through the quaint downtown and across the bridge that spanned the river that ran through the little city, which occupied a valley surrounded by rolling green mountains. Starker, darker mountains existed in every distance. From here, on his bike, on the bridge, he could see at once so many places he’d never been, would never go. He could see snow on a peak that was thirty miles away, a lone pine tree tiny on a ridge without a trail, what might or might not be a tent set up above a black scree.

This was in Missoula, Montana, a town as orderly and idyllic as the landscape a model train loops through, a town of some 60,000 people, a town eight hours from the nearest major city, Seattle. Together, these qualities – Missoula’s self-containment, its smallness, its isolation, its layered and intangible landscape – shrunk his range of concern and facilitated an ease he’d never felt elsewhere. Still, he was suspicious of it, this ease: life, for him, was a commodity, and he was frugal.

After the bridge, Ed took a gravel path that ran along the river’s bank. He stopped when he came to a little trail that led through some tangled brush, to a sandy beach where he liked to swim when the river was lower. Now, though, the river was still raging from winter, from the snowpack that was still melting down from the mountains. It was June.

Ed looked at the river. It traveled as fast as it could but it went nowhere. I’m like that, he thought.”

He took the trail toward the water, laid his bike down on the sand, sat on a log, and looked back to check that he was hidden from view. He was – but on the other side of the river, at the top of the high and steep bank, there was a Taco John’s franchise. The back of a Taco John’s franchise. There was a blue dumpster and a rusted a/c unit and some halfhearted small-town graffiti sprayed on the cinder-block side of the building and there was a drive-thru window and he wondered if the employees could see him through it. Maybe. Maybe not. Either way, they’d be too far away to matter, so he packed the fake cigarette and got high. But not too high. Just high enough to make everything a little less like it was.

Ed looked at the river. It traveled as fast as it could but it went nowhere. I’m like that, he thought. Then he thought, I’m high. Then he got up, got on his bike, continued down the path, and crossed the river again, this time via a pedestrian bridge, and rode through a hotel parking lot and waited at a stoplight and rode under an interstate that sounded like the river, except amplified. Ed turned off the busy road as soon as he could, into a dirt alley. He passed backyards. He passed garages and grass and a trampoline and a wooden boat overturned on a pair of sawhorses. He came out onto a street, turned again, and went as far as he could – a few blocks – to where the pavement dead-ended at a trailhead, where a sign provided information about invasive weeds.

Ed locked his bike to a young tree and started walking. The trail led to a giant ‘L’ made of poured concrete and set on the side of one of the green mountains that defined the valley. This mountain was Mount Jumbo. The next mountain over, Mount Sentinel, had an ‘M’ the same size. ‘M’ stood for the name of the town or for the name of the state university in the town or for both, depending who you asked. But the ‘L’ stood for a local high school called Loyola Sacred Heart, whose mascot was the Breakers, which pleased him, made him proud that the people here – a group that for the past year had included him – were so casually clever.

The mountain was relatively small, but the hike was still hard. The ground was green grass and loose rock and dry dirt, and every step he took made a little mess of the earth. It took a while but he got there and sat down exhausted on the white-painted concrete, beside a plaque that commemorated a student named John Tyler Howard who’d died a few years before, at the age, he calculated from the birth and death dates, of fifteen. No cause was recorded.

“Wry, sharp-eyed, fresh as mountain air.” Jonathan Trigell

Ed looked out at the mountains that made the valley that held the town. He saw the little Division I-AA (or whatever it was called now) football stadium and the crummy dorm that was Missoula’s tallest building and the interstate that would take you all the way to the ocean, if you wanted to leave, and the river that would take you there, too. In theory, at least. Surely something would stop you before you got very far. And Ed saw someone coming up the path. Two people. He saw them come closer and he saw, when they were close, that they were female and that he knew one of them, that she was a twenty-four-year-old nonfiction writer in the program whose name was Melanie and who, according to his friend Dave who’d had a workshop with her, exclusively wrote personal essays about how her mother was an unsuccessful folk singer who drove her daughters all over the country in a conversion van, playing gigs that barely paid. He didn’t recognize the other girl, but as Ed watched them approach, he saw she was blond and that she wore a light-blue tank top and short jean shorts and that she was thin and that she lagged behind Melanie a little.

He said hey to them when they were close and they looked up at him, out of breath.

Melanie gave him a little wave and said, “Oh, hey,” and stopped before him with her hands on her hips. She was wholesome, plain. The kind of girl who’s so sincere and has such a bad sense of humor that they’re difficult to talk to, like an aunt.

“How’s it going?” Melanie said.

“Good. It’s good. Nice day, huh?”

Then the other girl arrived and looked at him and breathed heavily, with an eager and shy smile that seemed to mean she was relieved to have arrived, and Ed saw she was disarmingly lovely. He wanted badly to be disarmed.

“This is Taylor,” Melanie said. “She’s a first year.”

By this, Melanie meant that Taylor would be starting their same graduate writing program in the fall. Their program was like a high school where angst had been replaced with irony.

Taylor’s skin was pale and her cheeks were flushed pink and her hair was long and blond and curled with a curling iron, he could tell, and her eyes were green and bright and the only way he’d be able to think of her later would be as a series of adjectives – girlish, pretty, radiant – but right now he was nervous and couldn’t think anything.

Ed introduced himself, put out his hand. Taylor shook it. Her hand was warm, and Ed felt shy, holding it. He let go and asked her where she was from.

“California.”

“Yeah? Where?”

“Oh, Southern California. The Mojave Desert. Kinda between LA and Vegas.”

“Is Death Valley in the Mojave Desert?”

“I think so,” Taylor said. “Pretty far north of where I’m from though.”

“I had a step-grandmother who was a fire lookout out there.” Ed hoped this would make him seem interesting and a maybe a shade blue collar, which is to say authentic, which of course he wasn’t, even though it was true, this fact about his step-grandmother, Joan. “But what would even burn in a desert?”

Melanie laughed a little, in an attempt at agreement, but Taylor looked at him mystified, like she wasn’t sure what he meant, what the joke was supposed to be, and she didn’t answer. Ed tried to convey with his expression that he didn’t know either, but he doubted this came across. He felt embarrassed, dumb. The three of them made bland introductory conversation for a little longer, and then Melanie said they should get going.

“Maybe we’ll see you later,” Melanie said.

“Maybe.”

Ed watched them walk back down the mountain. Before following them, he had to wait until they were way ahead, since it would be awkward to catch up and run into them again, so he lay back on the ‘L’, felt the sun and felt a shock of pain shoot through his arm, into his hand, where it echoed within the elements of his anatomy. His bones, his muscles, his nerves, and his blood. Or felt like it did. It was a common feeling, this shock. It happened every night when Ed lay in bed – except when he was drunk – and at other times, too, seemingly at random. It – the shock – originated in the golfball-sized tumor that had been growing on the inside of his bicep for nearly three years. The tumor sent pain into him but he pretended it wasn’t there, inside him, harming him.

The tumor was like the millions of children starving in Africa: too alarming to think about. It wasn’t like that: he could go to a doctor tomorrow and do something about it. But he didn’t. He lay on that letter, on that mountain, and he thought about Taylor, about how beautiful she was and about what she might be like and about how it might be to touch her and about how she might respond and about how she might become his and about how that would be, how perfect it would be, how jealous everyone would be, how proud he would be, and meanwhile cancer spread through his body. Or so he believed.

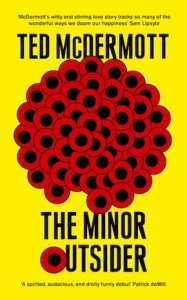

From The Minor Outsider.

Ted McDermott was born in 1982 and grew up in Columbia, South Carolina. His fiction and non-fiction have appeared in VICE, The Believer, The Portland Review, The Minus Times and elsewhere. He has been a baker, a mover, a cook, a college instructor, an encyclopaedist and a reporter. He lives in Missoula, Montana with his wife. The Minor Outsider, his first novel, is published by ONE. Read more.

Ted McDermott was born in 1982 and grew up in Columbia, South Carolina. His fiction and non-fiction have appeared in VICE, The Believer, The Portland Review, The Minus Times and elsewhere. He has been a baker, a mover, a cook, a college instructor, an encyclopaedist and a reporter. He lives in Missoula, Montana with his wife. The Minor Outsider, his first novel, is published by ONE. Read more.

tedmcdermott.com

Author portrait © Michelle Gustafson