Still hollering

by Jake Arnott

“Hard and fast and sure.” New York Review of Books

“Up to the age of thirty-one,” wrote Chester Himes, reflecting on the time that he was writing If He Hollers Let Him Go, “I had been hurt emotionally, spiritually, and physically as much as thirty-one years can bear: I had lived in the South, I had fallen down an elevator shaft, I had been kicked out of college, I had served seven and one-half years in prison, I had survived the humiliating last five years of the Depression in Cleveland: and still I was entire, complete, functional; my mind was sharp, my refexes were good, and I was not bitter. But under the mental corrosion of race prejudice in Los Angeles I had become bitter and saturated with hate.” Himes had come to LA in the early 1940s full of hope, the success of his short stories in Esquire had secured him a job as screenwriter for Warner Brothers. Then Jack Warner had him fired, declaring contemptuously: “I don’t want no niggers on this lot.”

And so a harrowing sense of disillusionment sets the tone for his first novel, just as his next job would provide the scene. Kicked out of Hollywood, Himes found work in that city’s other burgeoning enterprise, its military industrial complex, and served time as a labourer in a Naval shipyard. His fictional protagonist, Bob Jones, is a skilled ‘leaderman’ in the docks, one of the 70,000 African Americans who came to California during wartime with the promise of relaxed racial restrictions in the defence industry, only to find that they were treated the same as in the South, just with added hypocrisy. Amidst cramped decks and infernal machinery, Himes evokes a claustrophobic environment constantly on the brink of violence where race itself becomes a blunt instrument of struggle and oppression.

Coming into the plant, Jones observes that “the white folks had sure bought their white to work with them that morning”. With a sense of psychological incarceration that anticipates Foucault’s notion that “the soul is the prison of the body”, the narrative is circumscribed by an externalised consciousness and a segregated topography, tightly measured over four intense days with increasingly ominous dreams that insist that there is no escape, not even in the unconscious. Bob Jones is trapped by his diminishing sense of self, imprisoned by his own fear and desperation. Mike Davies in City of Quartz describes the novel as a “Dostoyevskian portrait of Los Angeles as a racial hell” and, like Raskolnikov, Bob Jones sees murder as a form of liberation. As he stalks a white man from the plant after a fight he muses: “as long as I knew I was going to kill him, nothing could bother me.”

We witness anxieties of colour amongst black people, tribal prejudice between the whites, an ever present danger of civil strife, a stark, apocalyptic warning in the mind of Jones.”

Race, of course, is the key issue but there are dimensions explored beyond the mere black and white: references to the Los Angeles ‘Zoot Suit’ riots in 1943, where white servicemen attacked Chicano youth, to the 94,000 Japanese Americans interned in California after Pearl Harbour. We witness anxieties of colour amongst black people, tribal prejudice between the whites (“don’t duck Okie, you’re tough” reads the graffiti on a ship’s bulkhead), an ever present danger of civil strife, a stark, apocalyptic warning in the mind of Jones: “Every day I had to make one decision a thousand times: Is it now? Is now the time?”

As a surreal impulse of self-destruction takes hold, the absurdity of racism becomes a prevailing theme. Bob Jones and Madge, a white woman worker at the docks, are drawn together in a lethal dance of fear and desire. Each the other’s most compelling fear and deadliest fantasy: “locked together in a death embrace; black and white in both our minds; not hating each other; just feeling extreme outrage.”

Though clearly part of the strong tradition of Los Angeles noir, the novel’s real strength is that it strips noir of its very mystique. We are faced simply with a struggle to exist between the extremes of seduction and terror. There is no mystery to solve. And we know all along what will be the worst horror of all for Bob Jones: “Not of the violence. Not of the mob. Not of physical hurt. But of America, of American justice.” Chester Himes’ popular legacy may rest on his later Harlem detective series – where the conventions of the genre could allow him a certain detachment (and long deserved financial security), but If He Hollers Let Him Go is his noir masterpiece. The crime it depicts remains unsolved; its message is still urgent.

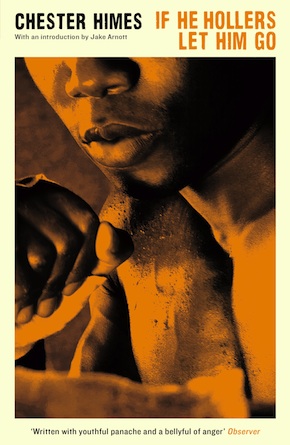

From the new edition of If He Hollers Let Him Go, published in paperback and eBook by Serpent’s Tail Classics

Jake Arnott is the author of six novels including The Long Firm, which was adapted as an award-winning BBC2 drama serial. His latest novel is The House of Rumour.

jakearnott.com