Hope Street and beyond

by Michael Egan

“A strange, intricate, haunting book – a confronting and otherworldly story about care and dependence, growing up and searching for home.” Jenn Ashworth

Even though the majority of Circles a Clover is set on an island that doesn’t really exist called Selny, part of it is set in Liverpool. I grew up in Liverpool and the city has always been something that pulled on me, told me to make it a character in my writing. To be honest, I resisted that for a long time. I didn’t want to be a writer of a place and I certainly didn’t want to be a writer of Liverpool. There was something that worried me about being a writer associated with the city, with my accent, that maybe it was too easy to pigeonhole Liverpool writers and the stories they tell. But as I got older and moved away from Liverpool, I found myself setting more and more of my stories in the city. The docks became the backdrop for a crime novel I started but never finished – the murderer being chased by my detective through the Albert Dock, and finally meeting his well-deserved end in the water of the Mersey with a bullet in his back. The streets of Huyton, where I grew up, became the backdrops for strange stories of creepy angels hiding beneath schools; of first love as pipistrelles circled St Michael’s church on Blue Bell Lane; the drunken tragedy of a man riding the 10A bus into Liverpool after losing everything. I wrote stories about Anfield, the Gormley statues further north on Crosby beach, Knowsley Safari, which always seemed so close to my childhood home but far away, and I set a novel about a great flood that devastates the world in the city – the Metropolitan Cathedral poking up through the water like the crown on the head of a drowned giant. The city started to work its way back into my psyche and my writing. Every poem I wrote seemed to wind towards the river, the Mersey flowing through everything despite my best efforts to be a poet not of place but of a freer language. It’s strange that I did this for so long – now all my writing is about Liverpool, the North West, so much so that even when I push my writing into sci-fi and fantasy, I see the city in the broken future and in the imagined other. And then I started writing Circles a Clover.

As Kyle leaves Liverpool, leaves her old life, the city offers itself as some kind of harbinger of strangeness, of darkness, of ambiguity.”

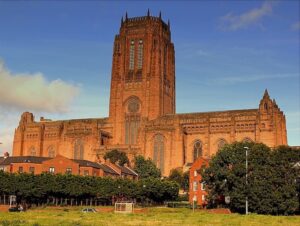

Kyle, the girl whose life is upturned by her father’s belief that the world is ending, has grandparents who live in the centre of Liverpool on Hope Street. Hope Street runs from the Catholic cathedral all the way to the Anglican, from the brutalist awe of ‘Paddy’s Wigwam’ to the precocious Giles Gilbert Scott’s vast gothic immensity. That setting, the space between the cathedrals, the affluence of the road with its townhouses and ornate iron railings, has often come into my writing, and whenever it does it’s also with a hint of magical realism. When Kyle visits her grandparents in Liverpool it’s with the knowledge that she’s leaving her life, her friends, and going somewhere she doesn’t really want to go. She loves her grandparents, but have they ever really been there for her? Childhood is gone and the outside world seems strange and dark, full of troubling possibility. As Kyle stands outside her rich grandparents’ house, she has a vision of a Shadow Liverpool that maybe digs into to the shadow life she’s living and the shadow island she’s about to go to. As Kyle leaves Liverpool, leaves her old life, the city offers itself as some kind of harbinger of strangeness, of darkness, of ambiguity. I’m glad that my city appears in this way in the book, because for me I’ve pushed Liverpool away too many times, told it not to butt into my head, but at this transition point for Kyle I like that it’s my city that offers the reader a glimpse into the fantastical world, and that it’s Liverpool that sets Kyle on her way to a place where the hinterland between reality and fable is foggy and full of uncertainty.

Circles a Clover is as much about place as it is about Kyle. The story begins in Hartford, Cheshire. A comfortable, middle-class village where no one admits that their life might be a bit messy. It jumps into an imagined place: Selny, a rabbit-shaped island near the Isle of Man, inspired by seeing a map of Sodor, the land of Thomas the Tank Engine, and another map of imagined places from literature. Fake Britain. But for a moment, just a chapter, it pauses in Liverpool and I’m able to bring my city into the story, into Kyle’s consciousness. Crows circle the cathedral. Kyle imagines them as the servants of a demon, maybe the demon that’s making her dad ill. She imagines the possibility of wolves howling, coming for her through the ruined city. She imagines that there will be no one to save her if the wolves come, and then she turns away and steps back into the inevitability of her story…

—

IT WAS LATE BY THE TIME they reached the bridge, the traffic blocked up all the way back along the expressway, every lane feeding in full of stuck cars as the sun set a brilliant red in the clear winter sky. There was no snow today and not a single cloud. The sky was like a lake of ice, coldest blue, and the world looked like it went on and on, unending. The huge chimneys of the power plant let out plumes of smoke, tinged with fire by the sun so it seemed like four squat dragons, mouths gaping, breathed their fire into the sky. She pulled her coat close about herself and tried not to feel so small, but as their car crawled closer to the bridge and she saw that the river too was alive with oranges and reds, she couldn’t stop looking at the sun, hanging there, gradually fading and colouring the world as it left the day. From the east there were purples and blurred blues reaching out, bringing evening, and the vapour trails of planes crisscrossed the sky like scratches on a perfect face. She closed her eyes and tried to imagine that their car was all there was in the world but it was no good; no matter how much she tried to make herself feel small and believe that, she could still feel the vastness of the world, the wide open sky, the jet streams that told the stories of other lives being lived, movement and motion, hear the radio, a woman’s voice, her dad’s fingers tapping. She opened her eyes and gave in. By the time they drove into Liverpool and along Hope Street, parking beside the cathedral just opposite her grandparents’ house, it was evening and dark.

The door was opened by the time they were at the steps and there were her grandparents, her mother’s parents, as old as they ever looked.”

She hadn’t seen her grandparents for nearly a year but the house was the same as always. A grand townhouse, high steps leading to a black door, freshly coated judging from the sheen of gloss, the lion knocker in its centre, the lion fiercely biting down on an iron ring. There was a basement they sublet to students from the university, fresh flowers in the low windows, and the attic was where she and Skan would always sleep, high up with the sash window overlooking the graveyard in the hollow beside the cathedral. The curtains, thick and red, were all drawn to keep out the night, but as her dad opened the wrought iron gate it set a little bell to ring and a light came on in the hall. The door was opened by the time they were at the steps and there were her grandparents, her mother’s parents, as old as they ever looked. Her gran was smiling, eyes moist so Kyle wondered if she had been crying or if that was just what happened to your eyes when you got old.

“My, you’re a sight for sore eyes,” said her gran, taking Kyle’s hand. Her hand felt so fragile, small, and Kyle tried to remember if it had always felt like that. Yes, her mum’s hands had been like that too. Fragile, the skin rice-paper thin, the light blue of veins almost shining out. Now her gran’s hand was scattered with liver spots and as she hugged Kyle, there was the old scent of Estée Lauder perfume. Kyle pushed her head close to her cardigan.

“We’ve missed you so very much,” said her gran.

“I’ve missed you too.” It wasn’t true, not really. There were some days when she knew she should call them, or worse than that when they would ring her phone and she would ignore it. She was never sure why. It wasn’t like she blamed them for her mum going; that happened long ago and they had been forever in her and Skan’s lives after that. It was only really since Skan had left that Kyle had stopped visiting them, stopped knowing with the certainty she had in childhood that she should love them. There had been a day, a week after Skan had phoned to say he had found a place in Brixton, when her grandad came to the house and for an hour there was shouting. She had heard something break and bad words, words she never thought her grandad could say. Now he stood with his arms out and she let him hug her.

“Where’ve you been, lass?” he said, his voice still tinged and layered with the soft lyrical tones of the Western Isles. He moved back and looked at her, his brow furrowed, his puffy lips dry and chapped. “You’re well, aren’t you?” And then he looked past her to her dad and his frown turned to a scowl.

She knew what he meant. Do you really want to go with him?

“I’m fine, Grandad.”

“Aye, well maybe we can all have a wee chat and catch up. We’ve supper in the oven if you’re hungry.”

Her gran’s hand was on hers again, china fingers curling about it. “You’re staying the night, aren’t you?”

“The ferry is first thing in the morning, Moira,” said her dad. He was calm, almost robotic. Like there was nothing wrong with him at all, like in his mind somewhere there wasn’t this tumour of a thought that everything was about to end. “I thought you’d like to see Kyle before we left.”

Her grandad’s scowl deepened. “Aye, you did. Well come on in inside, it’s a dire night.”

The hall was long, chequered black and white tiles running its length, and there were some of her gran’s paintings on the walls as well as a framed letter written to her grandad from Stephen Hawking and another picture of her grandad with a tall, bald man who Kyle guessed was another famous physicist. There was a picture of her mum and uncles when they were little beside that. It had always been in that same spot, like Jesus and his burning heart, but she wouldn’t look at it.

They ate pastitsio and her grandparents asked her about school.

“Science, is it?” said her grandad, happy. “I always hoped your mother had my scientific leanings; maybe they skipped a generation.”

Her gran touched her hand again. She had been doing it all through dinner, reaching out to her as if she was checking she was real, solid and actually there. Or maybe it was to hold on to her, thought Kyle. Maybe the next time she touched her hand she would hold it hard and refuse to let go, anchor her to them.

She patted Kyle’s hand tenderly. “There’s more to the world than atoms and quarks, Alistair.”

Her grandad pushed his fork into his salad and lifted up a slither of balsamic-drenched radish. “Aye there is, but nothing quite as grand as knowing why every little thing came to be.”

“What about the bigger things?” put in her dad. “You don’t need a microscope to see what the world is made up of.”

Her grandad sighed and laid his fork calmly on his plate. “I prefer to look a little deeper than what’s right in front of me to find my answers.”

Her dad had hardly eaten. “You can’t just ignore what’s going on around you, Alistair. That’s the problem with this world, too many people closing their eyes.”

Kyle looked to her dad. Even in his best shirt, even without the stubble and stained T- shirt, she could see the truth of him in his eyes. They were so tired, so sad. He couldn’t hide that from her no matter how hard he tried.”

Her grandad picked up his water and sipped it. He only ever drank water, not even tea or coffee, just water. “Jon, I can only hope that one day, for Kyle’s sake if not your own, you start to see that it does no good at all to imagine all the monsters of the world coming to your doorstep. If that happens, it happens. In the meantime, all we can do is look closer at our own lives and keep hold of what good we have. You have so much good, you always have.”

No one spoke. She could hear the clock on the mantelpiece ticking and a cat crying in the alleyway behind the house.

Her grandad looked at her. “Are you sure you want to go, Kyle? You can stay with us if you want, focus on your schoolwork. Surely, you’ve too much on to miss a day, let alone a week.”

Kyle looked to her dad. Even in his best shirt, even without the stubble and stained T- shirt, she could see the truth of him in his eyes. They were so tired, so sad. He couldn’t hide that from her no matter how hard he tried to hide it from her grandparents, it was the him that had been around for too many years now to suddenly just vanish.

“It was my idea,” she said quickly, looking from her gran to grandad. “I asked Dad could we go, you know, back to Selny because of all the holidays we used to have. We haven’t been anywhere for ages and I’ve got all the work I need with me. I haven’t had a day off since Year Seven; it’s hardly going to make me fail my GCSEs missing a week at the end of term is it? Besides, the doctor says Dad needs a break and I want us to have a nice Christmas, I want him to be better. All we’re doing is going away for a week, there’s no harm in that.”

Her grandad went to say something but her gran cut him off. “Listen to the girl, Alistair. She knows her own mind. I think she’s right, maybe the two of us should follow her example and have ourselves a wee holiday.”

Nothing more was said about Kyle staying. They ate a lemon tart her gran had made, the pastry as delicate as her hands, and the cream flavoured with whisky. The tart seemed to calm them all down and by the time their plates were empty it was like she was sat around a table with a normal family who did this all the time. No frowns, no scowls, no stubbornness. Just tea and words. It felt strange, out of place and false, and soon her feet began to jitter and shift beneath the table, desperate for a cigarette. She looked at her dad, smiling and talking about football, about Hibernian getting knocked out of the cup, as if everything was really normal, as if they had all only seen each other just yesterday, and her grandparents smiling politely back because they were nice people, good people, and this was how good people behaved. Even though there was more than a gap of years between them all. There was a hole, something missing, and not one of them mentioned it, not one of them mentioned her mother’s name.

“I might go for a walk,” she said. She wanted to smoke but that was only to get away and leave the falseness of them. It wasn’t really the need to smoke that made her leg shake. It was that they had no right to pretend there wasn’t a chunk of all of them missing.

“Ah, but do you not think it’s late, Kyle?” said her gran. “Wouldn’t you prefer me to show you your room? I bought you some new bedding, just in case. We couldn’t have you sleeping in a Power Rangers bed at your age could we?”

“She’ll be fine,” said her dad. “Just don’t be too long, Kyle. I need to talk to your grandparents in private anyway.”

She wondered if they were going to talk about her mum but then she realised the idea was ridiculous. Why all of a sudden talk about something you had refused to even acknowledge for over a decade? She could guess what her dad wanted to talk about. Money. Her grandparents had lots of it and they had so little. The end of the world was probably an expensive thing to run away from.

Her gran touched her hand one last time and looked at her so deep in her eyes that she wanted to turn away. “Don’t go too far,” she said and she kissed Kyle softly on her forehead.

Liverpool never seemed like an old city to her, everything was too new, even in the streets around her grandparents’ house. But the cathedral was like some fantastical castle, towering and gothic, imposingly dark against the black sky.”

Kyle lit a cigarette as soon as the little bell on the gate had rung behind her. The pavement was slippery with ice so she walked slowly along Hope Street, looking up at the townhouses and wondering what types of people lived there. One house had shutters instead of curtains and another had a huge terracotta Buddha in the drive. Another had eight different buzzers on the intercom and every window had different curtains. The house at the end was shabby, an old Saab rusting out front. At the end of the street she saw a group of tourists standing around a woman who was dressed all in black with a tall hat and white, ghostly face, her hands waving dramatically as she ushered them along the street towards the Catholic cathedral. She crossed to the Anglican and leaning on the railings she looked up at it. It was so high, so out of place. Liverpool never seemed like an old city to her, everything was too new, even in the streets around her grandparents’ house. But the cathedral was like some fantastical castle, towering and gothic, imposingly dark against the black sky. She blew out smoke between the railings. There were no birds flying above the high central tower but she imagined there should be crows circling it, a whole murder of them just whirling and whirling about the tower, ever circling. It didn’t look a good place, not like a church should look. It looked a bad and secret place where anything might be happening. She looked down into the graveyard, little tombs dotted about, forgotten, uncherished, grey obelisks and squat plinths, graves leaning into each other with names too weathered to know.

This wasn’t Liverpool, she told herself, this was another place, a shadow world, a Shadow Liverpool. She looked up at the cathedral. There were crows, hundreds of them circling the tower. They were a demon’s servants and if she were foolish enough to drop her cigarette and let herself be lured down into the graveyard there would be monsters waiting and the dead would want her to join them. She turned around and leaned back against the railings, looked at the posh town houses and imagined that they were all ruins, shells of what they had once been, like the old church down the hill; hollows, broken and useless. The whole city was that: a ruined place of too much evil, and she was alone, vulnerable. At any moment there might be howling and when the wolves came out of the alleys and ginnels she would have no one to save her but herself.

She dropped her cigarette and kicked it into the street. She took out her phone and took a photograph of the shabby house and uploaded it to her Instagram, tagging it with “My Hero”, wondering if Spencer would get that.

—

Her grandparents’ front door was unlocked so she let herself in. She could hear the three of them talking, her dad’s voice loudest but still calm. She climbed the stairs all the way to the attic and opened the door to her bedroom. All of her and Skan’s old toys were gone, the board games and even the Xbox. There was a new brown rug and her bedding was Cath Kidston. She undressed to her underwear and got into the warm bed. There was a small table beside it, different to the one that used to be there, and as she reached to turn the bedside lamp off she noticed there was a book with a folded piece of paper on top.

Kyle, I thought this might remind you of your mum and us. Love always, Granny xxx

It was an old edition. The corners were frayed and a little dog-eared. The cover showed a Roman soldier wearing some kind of animal as a cloak and holding a staff with a gold eagle at its top and a small sword in his other hand. The Eagle of the Ninth.

“Skan maybe,” she said quietly. It was Skan who had always read the book to her, not her mum. She didn’t have that memory like her gran thought she did, no memory of songs to lull her to sleep even. Her mum had left and with her had gone anything to fasten those memories too, so that as the years passed, whatever memory she had left of her became a ghost, fainter and fainter, until Kyle was unsure of what was a memory and what was a dream, made up to fill the gaps.

She opened the first page and there at its top was perfectly neat and scrolling writing in green pen. Paisley Smith, Liverpool, July 15th 1984. She switched off the light and turned on to her side, holding the book close to her body.

From Circles a Clover (Everything With Words, £14.99)

Michael Egan grew up on a council estate in Liverpool. He teaches English in Cheshire and is currently completing an MA in Prose Fiction at UEA as the recipient of a Booker Prize Foundation Scholarship. His poems have appeared recently in Glasgow Review, Prototype and The Fortnightly Review. He is the author of the poetry collections Steak & Stations (Penned in the Margins, 2011) and New Blasphemies (Contraband, 2022). Circles a Clover, his debut novel, is published by Everything With Words.

Michael Egan grew up on a council estate in Liverpool. He teaches English in Cheshire and is currently completing an MA in Prose Fiction at UEA as the recipient of a Booker Prize Foundation Scholarship. His poems have appeared recently in Glasgow Review, Prototype and The Fortnightly Review. He is the author of the poetry collections Steak & Stations (Penned in the Margins, 2011) and New Blasphemies (Contraband, 2022). Circles a Clover, his debut novel, is published by Everything With Words.

Read more

@northernashes

@EveryWithWords