Saša Stanišić: Alternative visions

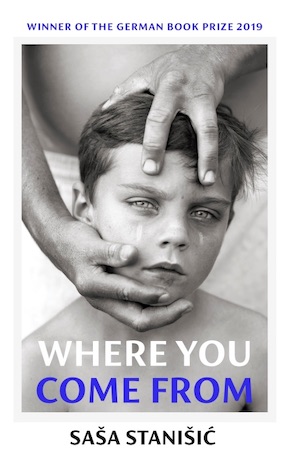

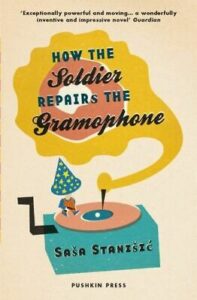

by Mark ReynoldsSaša Stanišić was born in former Yugoslavia in 1978 to a Bosnian Muslim mother and Serbian Orthodox father. Their flight into Germany at the outbreak of the Bosnian War in 1992 was fictionalised in his debut novel How the Soldier Repairs the Gramophone (Luchterhand Literaturverlag, 2006; Grove Atlantic/Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2008; Pushkin Press, 2015, translated by Anthea Bell). In his latest novel Where You Come From, he retraces his family’s journey from Višegrad to Heidelberg from the vantage point of his present life in Hamburg where he’s raising his own son. Partly autobiographical, often taking the form of journal entries reflecting on the past and present, family myths and fables, exile and assimilation, heartbreak and joy, it also embraces wild flights of fancy, concluding in a beguiling Choose Your Own Adventure section that tests the boundaries of the real and the imagined.

Mark: The German title translates as ‘Origin’ (or ‘Origins’). Why the title change, and did you initially resist it at all? The notion of origin – or where you come from – is approached from multiple angles throughout…

Saša: Both titles work in a similar way, through asking an indirect and open question, an offer of sorts, for readers to maybe think about what their ‘origin’ is, where they ‘come from’. Answers to both are, hopefully, not one-dimensional. There are numerous possibilities to define oneself: a productive search for important features in one’s biography, but also a view into being externally defined and other-directed.

How closely did you work with Damion Searls on the translation, and were there any surprising turns along the way?

We worked closely on the first half of the book, then I had to step away from the process, since many scary angry deadlines were looming. Since I speak some English, I saw the work on the translation as a possibility to rewrite some stuff that I didn’t like in the original anymore. So, if you buy the UK version of the book, you get the freshest update.

Did Damion use Anthea Bell’s translations of your previous books as a touchstone? The tone is remarkably consistent and utterly recognisable.

I do not know. Do translators do that? I like the idea.

I wish we defined ourselves by the landscapes. Like: ‘I come from a mountain with many pines and firs, what about you?’”

The country you were born into no longer exists, and when you visit your great-grandparents’ village it has only thirteen remaining residents, yet the landscapes are more or less unchanged. How do these things make you feel about nationhood and belonging?

Kind of sad. I wish nations were never invented or constructed: how many wars and deaths and all kinds of crap would have never taken place? I wish we defined ourselves by the landscapes. Like: “I come from a mountain with many pines and firs, what about you?” “I grew up next to a waterfall!” “You guys are really interesting – all I got is a shitty meadow.”

This is your most autobiographical book to date, whilst also revisiting themes, events and locations in How the Soldier Repaired the Gramophone. How do the narrators – and the purpose – of the two books differ?

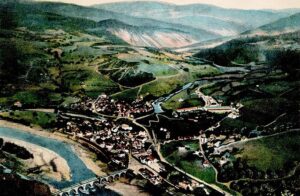

Colourised postcard of Višegrad valley and the rivers Drina and Rzav. Verlag Josef Schreiber, 1906/Wikimedia Commons

The two books are circling the subjects of war, family and identity in times of crisis from different ‘heights’; The Soldier… is closer to the characters, with an imagined child narrator, and farther away from my own biography. The narrative of Where You Come From is more diverse in style, and its mosaic structure feels to me broader in dealing with the above-mentioned subjects, parts of it being much more personal, others being researched and far away from my own experience. I guess the books go well together – so my advice is to buy them both and also gift a copy to a friend!

The German edition of Where You Come From wasn’t labelled as a novel. Did it predominantly end up on the fiction shelves of bookstores nonetheless? And how do you feel about the label ‘autofiction’?

I do tend to go to bookstores and move my books to a more prominent spot, so yes, I know the answer to the first part of the question: they were in the ‘recommended fiction’ section. After I left they were everywhere, though. I love to put one in the ‘German Tanks and Airplanes’ section.

Labels: I guess we do need labels, don’t we?

The episodes about your grandmother’s dementia are heartbreakingly tender. How did being a storyteller help you cope with her decline?

The interesting thing about my grandmother’s sickness was that she became a storyteller herself and filled in the blanks of her memory with many, many stories. Some of them touching and truly sad, some absurd and funny. We told her many stories too, to soften her frustration of feeling helpless in the wake of dementia and losing memories, thus losing herself. She particularly felt an urge to ‘go home’, even in the moments where she was at home. It was devastating to see her like that – knowing that there is a place for her that she called home, but not being able to be there emotionally.

Read an extract: ‘Grandmother and get me out of here’

The Choose Your Own Adventure chapters at the end of the book are a fabulous way of blending memoir and fantasy, and exploring the boundaries between memory and fiction. How reliable are the tales of you and your grandmother’s encounters with dragons?

Very reliable, of course.

Your son appears to have inherited your love of inventing things. At what age did you begin making things up, compared to him? And what does your son currently hope to be when he grows up?

He does not believe that being a writer is a ‘real job’. And he is right, of course, since most writers are not paid enough for what they do.

He thinks that a true job is only if you create something concrete and visible (like a bridge or a robot), or you sell stuff, or you have a task that, you know, changes a condition to some other condition (a sick person to become healthy again).

He does believe in the power of storytelling though, and he uses this power by really letting his fantasies roam through whatever beautiful and weird worlds children’s brains are capable of inventing. I admire and love that very much.

That said, he already, at the age of 6, co-authored a children’s book with me and has received an award for his work. So now he not only does not believe that writing is a job – he believes that it is the easiest thing: you write a story and get an award…

I do believe that my childhood was really special, but I don’t hold the country accountable for the beauty and freedom of it – rather my parents, friends, school.”

How has fatherhood affected your writing? Was becoming a father a major trigger to writing more directly about your family?

It was a trigger to write children’s books! Already did two and it feels great. So much less pressure.

What are you writing next?

A children’s book.

You were awarded the 2019 German Book Prize for Where You Come From, and have since been awarded the 2021 Schiller Prize. What do those particular awards, and literary prizes in general, mean to you?

Well, money. Also I get to hold speeches at award ceremonies, which makes me feel important, and there is always a really nice dinner involved.

What do you miss about Yugoslavia, and how do you feel it is remembered within its former borders and beyond?

I was really too young when we left to become overly nostalgic. I do sometimes think of my childhood: how the whole city was our playground, how the rivers felt when I went swimming, how I discovered computer games, girls, and all the other ‘firsts’ of being a kid and teenager somewhere.

Most of these nice memories are pretty much disconnected from ‘Yugoslavia’ as a concept. I do believe that my childhood was really special, but I don’t hold the country accountable for the beauty and freedom of it – rather my parents, friends, school.

The break-up of Yugoslavia also resulted in the break-up of one of Europe’s strongest footballing nations and the dismantling of Red Star Belgrade’s multi-ethnic European Cup-winning squad. Can football help mend broken bridges?

No.

Do you still follow Red Star, or have you switched allegiance to Hamburger SV?

Do you still follow Red Star, or have you switched allegiance to Hamburger SV?

I do have an app that sends me a message when a game involving Red Star is finished, so I get to see the results. They have a really radical and aggressive right-wing, nationalist fan base though, and that makes it impossible for me to truly connect to their successes.

And Hamburg – well, this team has been a complete disaster in the last few years. My love is not waning, but my nerves are very thin.

At this point, as an Aston Villa fan, I want to lever in a question about 1990s club legend Savo Milošević. Can you help?

I have been too far away from Yugoslavian football, but wasn’t he a Partizan player? They, as you might now, have been THE rivals for Red Star throughout all times.

How often are you still asked where you come from, and how do you tend to reply?

It does happen from time to time in Germany when people see my name and all the letters that don’t exist in the German alphabet. I keep my answer very pragmatic: “I come from Yugoslavia but have been living in Germany for many years now.”

If I am in a playful mood, I invent a country that sounds Slavic: Markenlonia for example. And then I make up a story about a mountain where I was born – with many pine and fir trees …

Where do you come from?

Brusnia, but I have been living in Kruppflaz for many years now.

Saša Stanišić was born in Višegrad in former Yugoslavia in 1978, moved to Germany when he was fourteen and studied at the Deutsche Literaturinstitut in Leipzig. His novels How the Soldier Repairs the Gramophone and Before the Feast have been translated into more than 30 languages. His novels and stories have been awarded numerous literary prizes. For Herkunft (now published in English as Where You Come From) he received the German Book Prize 2019. Most recently, he was awarded the 2021 Schiller Prize of the City of Marbach. He lives and works in Hamburg. Where You Come From, translated by Damion Searls, is published in hardback and eBook by Jonathan Cape.

Saša Stanišić was born in Višegrad in former Yugoslavia in 1978, moved to Germany when he was fourteen and studied at the Deutsche Literaturinstitut in Leipzig. His novels How the Soldier Repairs the Gramophone and Before the Feast have been translated into more than 30 languages. His novels and stories have been awarded numerous literary prizes. For Herkunft (now published in English as Where You Come From) he received the German Book Prize 2019. Most recently, he was awarded the 2021 Schiller Prize of the City of Marbach. He lives and works in Hamburg. Where You Come From, translated by Damion Searls, is published in hardback and eBook by Jonathan Cape.

Read more

@sasa_s

howtowaitforalongtime

@jonathancape

Author portrait © Katja Sämann

Damion Searls is a translator from German, Norwegian, French, and Dutch and a writer in English. He has written for Harper’s, n+1, and The Paris Review, and has translated the work of authors including Rainer Maria Rilke, Marcel Proust and five Nobel Prize winners. The recipient of Guggenheim, NEA, and Cullman Center fellowships, he is the author of The Inkblots, a history of the Rorschach Test and biography of its creator.

damionsearls.com

Mark Reynolds is a freelance editor and writer, and a founding editor of Bookanista.

@bookanista

wearebookanista

bookanista.com/author/mark