Not quite the way to the stars

by Mika Provata-Carlone“O, it is excellent / To have a giant’s strength; but it is tyrannous / To use it like a giant.”

Shakespeare certainly knew his Romans; even though the lines that capture so brilliantly – and devastatingly – the allure of power and its raw brutality come from Measure for Measure, they could well have belonged to any of his so-called Roman plays, such as Titus Andronicus or Julius Caesar. The latter play in fact contains the crucial distinction between human power and monstrous force: “Th’ abuse of greatness is when it disjoins / Remorse from power.”

The fact that Shakespeare lacked most of our own knowledge and understanding of the ancient world, our access to texts, material culture, archaeological evidence or anthropological and ethnological insights, speaks volumes not only about his brilliance as a writer, and as a thinker about human nature and history, but also about how much the Romans have never ceased to fascinate those who came after them. Not simply because of who they were, but above all because of the Medusa-gaze mirror they provide about who we are.

Shakespeare wrote about the Romans (as he wrote about the Greeks, the Danes or the Italians, the a-historic Scots) in full awareness that they were for him the catalysing factors that would allow him to give voice to the singular, exceptional individuals caught between destiny, inevitability and choice, as well as to the multitudes whose words form the writhing body of his texts. He wrote not so much about them, as through them, always on the strength of his unique genius of “two distincts, division none”: his art involves no cultural appropriation, but the appreciation that the properties of one culture enhance, elucidate, bring to the fore another through methexis, the Aristotelian participation in the experience that is (or seems to be) not at all our own. The questions of power and vulnerability, of will and destiny, of choice, domination or subordination are always key to his unswerving quest for what makes us human – or not quite so.

Toner boasts a strong, flowing storytelling voice that lulls readers into impish complicity, luring them unprotesting to the darkest, smelliest, foulest revelations.”

Jerry Toner’s latest magisterial study-cum-rambunctious, galloping story of Rome, Romanitas and Roman mores, can be said to be cut of very similar cloth. The unabashed brief of Infamy (and yes, the pun and cultural reference are fully intentional) is to “put Rome on trial”, to “show Roman society in all its guises: practical, flexible, innovative, brutal”, vile and magnificent, awesome and highly problematic. Above all, perhaps, to make us reflect about our own foundation stories and cultural myths, the structures and the porous groundwork of our own social and civilisational edifices. All the roads lead to Rome, according to the familiar adage, and for our own Western civilisation a reflected retrieval of that incipient moment that formed our character and shaped the conditions of our belonging to the world is crucial if we are to address what Toner terms “our own world’s contradictory tendencies… Rome provides both an early inspiration for the consumer individualism of the modern world and a revolting example of what happens when it gets out of control… What we love about Rome, is also what we hate about it.”

Brace yourselves as you embark upon the story he unfolds. If it is greatness, pax and gravitas you are after, your expectations will be mightily deflated, just as they will be magnificently entertained. Toner boasts a strong, flowing storytelling voice that lulls readers into impish complicity, luring them unprotesting to the darkest, smelliest, foulest revelations about “why the Romans had been so successful and what had made them so great.” Beginning with the “shameful secret in their ancestral closet”, the foundation story of the twin brothers Romulus and Remus, Toner conjures up a staggering image of human suffering and frailty, ambition, resilience and achievement, of unspeakable savagery and ruthlessness. Taking his cue from Gibbon’s sharp assessment that Rome’s road to glory was “a perpetual violation of humanity and justice”, Toner offers a scathing critique of both “the Roman capacity for violence” and their conscious, systemic and institutionalised normalisation of that element they saw as inherent and organic to their nature, an inbred vicious streak that afforded them endurance against adversity and the stamina and deliberation to repel and to conquer. He also carefully and with meticulous, scholarly integrity sets out to show the gigantic effort required in building a global society – or even a tiny, local one.

Under Toner’s examination will come not only the Caesars, the emperors or the ruling classes, but especially the people, the populus romanus so exalted by those who ruled them and swayed them, manipulated or exploited them. This common humanity, often called the plebs, or even the faex populi (an expression to be picked up later by Lafontaine in one of his most famous fables, ‘The Lion and the Gnat’, as “the excrement of the earth”), were both textbook victims and eagerly compliant accessories, will-less military fodder and serving apparatus of the civic system, and the powerhouse of Rome’s strength: they had “internalised the ideology of the ruling classes and thereby became ruling participants in empire rather than its subjects.” Infamy aims towards an annalistic exploration from low to high rather than from high to low, drawing upon epigraphic evidence, material culture, the masses of judiciary minutiae and records that survive in the treasure trove of the Oxyrhynchus Papyri, on astrological manuals and joke books, as well as on more typical historiographical sources, stretching our scholarship and our imagination beyond the official corpus. Fiction and rehearsed reality (rhetoric, philosophy, the textual ‘mocks’ and cribs produced by aspiring lawyers as they prepared themselves to face the unpredictable, the unimaginable or the impossible) are at the core of his vast survey that stretches from the Late Republic to the borders between Late Antiquity and Early Christianity. In more ways than one, Infamy provides the story of the facts behind just about everything we think of as Rome, from the texts and life acts of the Romans themselves, to our own very contemporary engagement with them – from Robert Graves’ Claudius novels to Tony Harrison’s The Trackers of Oxyrhynchus, and everything betwixt and between.

Were the Romans angels or daemons? Was Rome a culture of supreme order or total brutality? It was above all, Toner argues, a culture of inherent extremes and contradictions.”

Toner has an alluring talent for being a particularly clear-sighted reader and historian, enhancing perspectives, calibrating scales of judgement, engaging us on a journey of tumultuous pace, whose point of arrival is the stark encounter with everything, positive or decisively less so, that lies at the heart of the Roman psyche. Were the Romans angels or daemons? Was Rome a culture of supreme order or total brutality? It was above all, Toner argues, a culture of inherent extremes and contradictions, and the greatest, critical interest that it holds for us lies in the way they reconciled, embedded, normalised and glorified such polarities. If Greece thought of itself as exemplifying the Golden Mean and Measure, Rome prided itself on being the brazen extremist, the sublime eccentric, the master-craftsman of excess and transgression. The atypical, it emerges from Toner’s strong argument, is in fact the quintessential Roman type.

Toner’s narrative is suspenseful, energetic, yet also deeply thoughtful, evincing a quiet, untiring urgency that arises from an engagement with ethics at the most primary and fundamental level. This is a fearless contemplation of Rome – as well as of ourselves, our vision for the present and future society. His method is to try and assess whether violence, brutality, inhumanity were inherently symptomatic of or exceptionally circumstantial to Roman character. He will examine causes and effects, weaving together stories of chilling yet engrossing vitality, so that at every step “we can almost hear the screams echoing off the page” or feel “the crack of the whip coming off” the papyrus scroll – pages, any fragments of writing surfaces, hold a palpable, electrifying fascination for him, whether they are pages that are relatively familiar to us (Cicero, Suetonius, Tacitus, Lucan, Seneca, Pliny, Polybius, Cassius Dio), or the more historiographical evidence of ledgers, archival material, law records and books, or even scraps found in rubbish heaps. Words are the flesh and blood of real-life stories, conjuring up characters who will not easily let go of his reader’s imagination and moral conscience.

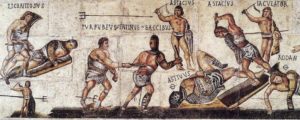

Through vivid anecdotes, apocryphal stories, utterly astonishing snippets of Roman wisdom (“Pliny recommends wearing the right foot of a chameleon tied to the left arm by hyena skin as a powerful protection against robbery and other terrors of the night”), or hard textual facts, such as laws that intricately defined the price of a human life, but showed, as Wilde might say, a total disregard for its value, Toner fleshes out the various circumstances and forms of Roman violence as both an ideological precept and an ontological feature of Roman society. We move from small village communities in Egypt to Rome itself, the megacity of a million souls, to the Italian countryside, to Britain and the city of Bath, or the Aquae Sulis of the Romans, in search of patterns, human traces, the ghosts of many lives. Murder, assault, rape, civil disobedience, state policies of terror, the persecution of criminals and Christians, gladiator games and the Circus Maximus, law and the judicial system covering the appropriate use of extreme force such as the lex ulciscendi that ratified the right to revenge, fear as an existential social state and as a powerful element of authority, emperors who were “mad, bad and dangerous to know”, but also measures to contain, pre-empt or castigate antisocial behaviour are the stops along the road towards an understanding of what made the Roman empire, that vast conglomerate of classes, nations, geopolitics, lives and attitudes to life, possible at all.

Brute force and mercy (or clementia) held equal sway in this astounding balancing act that was Rome: “terror and clemency represented the two sides of the same coin”, forming a conscious and articulate public and private strategy. Behind both lay a desire and a need for power – power as an agent of control but also as the force that bound what was irreconcilable and disparate into an almost flawlessly coherent whole: “a good rule of thumb, in Rome, as in life, is this: never attribute to reformist zeal what can be explained by the simple consolidation of power.” The tension between peace and war, humanitas and violence, produced a sense of focus, a feeling of purpose or of urgency that was as unflinching as it was unthinkable – and unbreakable: “Today we tend to think it better to find a peaceful solution to disputes, and regard violence as symptomatic of a breakdown in the process, but in Rome it often seems that violence was considered the proper way to settle an argument [at any level]. It often took ritualised forms and could generate a powerful sense of community. In a sense, perhaps, it played a positive social role.” Nothing is a stronger gelling agent than a relentless ‘Us vs. Them’ tension, from the triumphal processions to the gladiatorial contests, to Nero’s loutish night prowling, which he would try and pass off as a way of showing he was one of the people, to the fustuaria, a favourite practice of Augustus to prevent mass cowardice in war – when a Roman army unit had been defeated in a particularly dishonourable manner, it would be split up in tens, then one man would be selected from each group by lot to be clubbed to death by his comrades in arms, according to Suetonius.

He combines the liveliness of powerful human narratives with astute sociopolitical and philosophical analysis to create the space for unheard voices, untold stories, uncharted lives.”

Andrew Lintott and William V. Harris have shown how an ethos of anger, ira and iracundia (irascibility), the very “language of revenge” were fundamental to Roman identity, from ultio (revenge) as a form of public and international policy, to the exempla severitatis that kept the people docile, and in Infamy Toner combines the liveliness of powerful human narratives with astute sociopolitical and philosophical analysis to create the space for unheard voices, untold stories, uncharted lives. In doing so, he straddles the perceived distance between a monograph and a work of eminently readable social history, revealing the relevance of what was overlooked because deemed to be unworthy of attention (even Asterix the Gaul receives a memorable, highly intriguing mention). Fundamental to his argument is the notion of privileged versions of history, of hegemonic narratives, of the need to redress the balance between selective and inclusive perceptions. As he has written elsewhere, in ‘Barbers, Barbershops and Searching for Roman Popular Culture’, the problem of exploring Roman daily life is “that this task involves texts that were written almost entirely by members of the élite.” Equally central is the responsibility we ourselves hold to be judicious and fair interpreters of history rather than complacent revisers. Toner is never unforgiving, but he is a precise and demanding critic – of Rome, of the Christian empire(s) that followed, of our own post-Roman, post-so-very-many-essential-things modernity.

Roman Gladiators with Wooden Swords by Giovanni Francesco Romanelli, c. 1635–39. Museo del Prado / Wikimedia Commons

Underlying Infamy is infinitely more than just the recording of acts of and the proclivity for violence or power. What is also a crucial perspective is that Rome did not define itself as das Ding an sich, the thing in itself, but rather, and consistently, invariably, deliberately, in juxtapositional, comparative, adversarial terms. As long as the tension between Romans and a hostile Other held strong, there was an almost oxymoronic sense of chaotic unity, of amorphous form. Military impetus would not have been sustainable otherwise, and the same vital strain on a social level rendered a more substantial, humanistic legal and political system unnecessary. It also muted the need for critical thinking and for critical response (some readers may find such political features somewhat familiar). Christianity would challenge and eventually demolish this traditional sense of Romanitas. In the West, the Roman empire would have to collapse and dissolve in order to reform again as the multitude of Christian nations into which it evolved. In the East, a different story can be told – beyond the scope of Toner’s own enquiry, of how breach and continuity were possible because of the failed (or in fact unattempted) Romanisation of the Greek East beyond the bureaucratic, administrative level. There, Christianisation would emerge as a critical revision and development, a synthetic, syncretic process of becoming, whose own challenges, pitfalls and failures would be quite distinct from those of the more properly Roman West.

Toner’s Infamy stops where these two divergent paths begin: like Graves’ Claudius, he seems to say “write no more now, Tiberius Claudius, God of the Britons, write no more”, though perhaps his take is more Augustinian than full of bloody murder. He leaves the reader with a sense of both thrill and anguish, a feeling of deep contemplation and the necessary open-endedness that will lead to a radical engagement with both past and future. Above all, Toner bequeaths his reader with a precious legacy of serious humanity – of riveting human seriousness. Infamy is an extraordinary story of our history, a prophetic alarm call for our future.

Dr Jerry Toner is Fellow and Director of Studies in Classics at Churchill College, Cambridge. He is the author of How to Manage Your Slaves and Release your Inner Roman, which were published by Profile under his pseudonym Marcus Sidonius Falx. Infamy: The Crimes of Ancient Rome is out now from Profile in hardback.

Dr Jerry Toner is Fellow and Director of Studies in Classics at Churchill College, Cambridge. He is the author of How to Manage Your Slaves and Release your Inner Roman, which were published by Profile under his pseudonym Marcus Sidonius Falx. Infamy: The Crimes of Ancient Rome is out now from Profile in hardback.

Read more

classics.cam.ac.uk

@ProfileBooks

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.