Into the lagoon

by Audrey SchulmanAs soon as her head was under the surface, the dolphins’ noises filled her. Sound, bright as light, hard as touch.

Ping-pong balls bouncing down metal stairs.

Dolphins are constant vocal innovators, playful geniuses with unspeakable power, the Maria Callases of the sea, their sounds unworldly and pure.

A gospel group on helium, hitting the high notes.

She found herself wiggling a little deeper into the water. Two feet deep, two and a half. She saw white sand, a crab scuttling sideways and the pilings of the dock.

A tired mouse crying.

She barely paid attention to her surroundings, her entire being focused on the sounds. She inhaled through the snorkel and felt the sounds in her lungs.

Styrofoam squeaking.

The noises were vibrating in her bones, she tasted them on her tongue, saw them between her ears. So clear and crisp and three-dimensional.

Martians arguing, metallic and intent.

Just beyond, a dolphin flashed by, big and gleaming. Surprised, it spotted her and, with a flick of its tail, was gone.

Now the sounds got louder. Excited. The crying, the clicking. She eased forward deeper, floating now, balanced on just her fingertips, breathing through the snorkel, the waves sloshing across the top of her head.

Around the corner of the dock, the dolphins were revealed.

Clustered on the far side of the lagoon, maybe 60 feet away, they stared at her. Their presence, their sheer size. The largest one (at least 11 feet long, must be over 450 pounds) floated in front, the three others behind. The positions a family would take if she walked in with a gun.

They geigered and squealed in her direction. A crinkling sensation like plastic wrap twisting in her gut. The sound exploring her insides.

The big one opened its mouth and clapped its teeth. Agitated. It had a red mark across its chest, maybe a rope burn. It held its flippers out to the sides and arched its back, trying to look even bigger than it was.

The two medium-sized ones stayed just behind, one to either side. One of them had a gash along its right flank, probably 6 inches long. These two kept their bodies between her and the fourth dolphin who was almost the same size, probably an adolescent. The adolescent peered around them, shifting from side to side, trying to see, clicking at Cora.

Scared. Not used to humans. Perhaps their injuries were from being captured.

From twelve years old on, she’d worked part-time at the horse stable next door, Beach Ride Bobby’s. There, she could muck out stables, groom and saddle the horses, with hardly a person speaking to her all day. With the dolphins, she acted the way she would when the horses were jumpy. She didn’t freeze motionless, staring the way a predator would. She turned away and acted busy.

She relaxed her body, breathed slowly through the snorkel, and listened to the dolphins’ sounds gradually calm down. The noises washing through her.”

She’d always felt relief being with the horses, perhaps because they talked with their bodies, with their stance and ears and tails, stepping forward or away. This type of language was so easy to read. Over time she learned to speak back. She moved confident and relaxed, approaching always from the left, clucking to give them warning. Touching the fetlock meant pick up your foot, her hand on the ear meant lower your head, her posture leaning back in the saddle meant stop. She spoke with her body. Go left. Faster. Canter.

The horses told her with their ears and posture and stride if they wanted to run, where they wanted to go, if they trusted her. Riding a horse was a dialogue that could range from a choppy argument to a joyful conversation.

Floating in the shallows, she rummaged in the sandy floor of the lagoon, searching for mussels. She was someone going about her day, uninterested and occupied. She relaxed her body, breathed slowly through the snorkel, and listened to the dolphins’ sounds gradually calm down. The noises washing through her.

A squeaky floor.

Castanets clicking.

Occasionally, at the purity of the sounds, her eyes fluttered closed.

Stars sizzling in space.

By the time she’d found the tenth mussel, the dolphins were surfacing regularly to breathe. Each exhale sounded like a soda can opening, the pssh of pressure releasing. They’d begun to drift closer, curious about her.

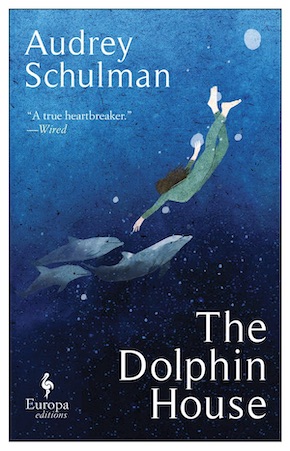

from The Dolphin House (Europa Editions, £12.99)

Audrey Schulman is the author of five previous novels, including Three Weeks in December (2012) and the Phillip K. Dick Award-winning Theory of Bastards (2018). Her work has been translated into eleven languages. Born in Montreal, she now lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts where she and her husband run the not-for-profit energy-efficiency organisation HEET. The Dolphin House is published by Europa Editions in paperback and eBook.

Audrey Schulman is the author of five previous novels, including Three Weeks in December (2012) and the Phillip K. Dick Award-winning Theory of Bastards (2018). Her work has been translated into eleven languages. Born in Montreal, she now lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts where she and her husband run the not-for-profit energy-efficiency organisation HEET. The Dolphin House is published by Europa Editions in paperback and eBook.

Read more

audreyschulman.com

@AudreySchulman

@EuropaEdUK