Laline Paull’s hive society

by Farhana GaniThe literary world is buzzing over a remarkable debut novel featuring Flora 717, an unlikely heroine born into the lowest ranks of society and breaking free to achieve like no one of her kind before her. Flora happens to be a bee.

Described in some quarters as Animal Farm meets The Handmaid’s Tale, Laline Paull’s enthralling story enters the mysterious realm of the beehive – the architecture and hierarchy, the rituals, scents and signals.

Flora 717 is a Sanitation Worker, the lowliest of the lowly, destined to mutely clean out the hive and dispose of its dead. But times are changing in the kingdom of the hive and whilst her abnormal appearance would usually mean instant death, Flora attracts the attention of a member of the ruling class who finds her variation – grotesque as it is – a personal challenge and Flora’s fate is dramatically altered.

So begins the epic set in a totalitarian hive state where Accept, Obey, Serve is life’s purpose; where the Myriad threatens, the drones are lewd, death is messy, Devotion calms the senses and The Kindness is terminal. Every bee knows her place, only the Queen lays the eggs, and order is maintained. Or is it?

The Bees is a thrilling feat of imagination about a hidden society, a page-turner with a deft turn of phrase and a multitude of characters that linger long after reading. I found myself rooting for Flora from the moment she emerged from her egg, wings still wet and fighting for survival in a world short of food and trust but bursting with the ‘Queen’s Love’.

Paull tells me about the nature of bees and the wisdom of animals, and various other aspects that shaped her audacious and satisfying debut.

FG: Bees are social insects and collaboration and an elaborate communication system appear to be the essence of their survival. You’ve captured that brilliantly in showing us how the bees share information with each other and absorb and identify scents and signs with their antennae. Was it easy to anthropomorphise the bees?

LP: When I learned about the real phenomenon of the laying worker, I became very excited. All worker bees are sterile females, but very rarely (one-in-ten-thousand rarely) one will start to form eggs in her body, and then she will hide them and try to hatch them out. So from this it was an instant of sympathetic imagination, to become that criminal in the hive, who will put motherhood above the law. And Flora 717 was born in story form.

Animals have courtship rituals, they like nice homes, they don’t want trouble. They want to breed, they want to eat well, they want their children to survive. We’re animals too.”

Are you an advocate of animal consciousness?

Most definitely. Animals feel fear and pain, they will sometimes sacrifice themselves for each other, some species bond for life. Hippos and elephants apparently show mourning behaviour. Animals have courtship rituals, they like nice homes, they don’t want trouble. They want to breed, they want to eat well, they want their children to survive. We’re animals too. And as we have taken over the planet from every other animal, we have a duty of care which is all too often neglected. We have a humane duty not to ship animals alive for slaughter, we have a duty not to destroy precious and irreplaceable natural habitats and habits. And if we persist in ignoring our moral responsibilities and treating animals and the natural world like an endlessly renewable resource, we are sowing the seeds of our own misfortune.

The Bees is being described as dystopian – was that your original intention?

It wasn’t, but The Bees has been called that so often that to answer your question I thought I’d better look up what dystopian really means: “An imagined place or state in which everything is unpleasant or bad, typically a totalitarian or environmentally degraded one. The opposite of utopia.” I didn’t specifically imagine the beehive as bad, but it is a totalitarian state for the species of Hymenoptera, which includes bees, wasps and ants, in which the rule of law is that only the Queen may breed, and it has been that way for at least 40,000 years. And so to step outside that system usually would mean death. So that is bad and dystopic – but only if you’re a rebel, with courage and individualism. Like my protagonist Flora 717.

Your story is told entirely from the perspective of Flora. Can you talk us through how you came to structure the novel from her point of view and not, say, a drone, or the Queen?

If you want to tell a story and you start with someone at the bottom of a hierarchy, there’s only one way to go, and many myths and legends use that pathway. I did consider telling the story from a drone’s perspective, one who survives the massacre of the males and gains an entirely new understanding of his place in the world, but I decided to go with the laying worker, because the potential for cataclysmic social change was greater in that story. But I did write a whole outline for the Drone’s Tale, and also one for how the Queen came to rule this particular hive, which was not straightforward at all. But I have a thing for the underdog, so Flora won out.

The caste system in a hierarchical society stands out as a central theme in the novel – every kin knows their place and promises to serve the greater good of the hive. The Sanitation Workers are very much like the Untouchables in India. Did you have a particular human hierarchical society in mind as you structured your novel?

Ah, the Dalits; you have correctly identified one of the influences in this work. The idea of the vertical caste system is repellent to me, and yet it is a fact of many societies. I can’t do anything about it in this world, but I could express my strong belief in the power of nurture, easily as much as nature, in this story. Switch two babies at birth, put one in a palace and one in the most economically deprived area of the country, and which one do you think will do better in life? We all know the answer, and we also know it isn’t fair. Which is why politics is so important, and people who don’t vote must be seriously disillusioned if they don’t use their voice to try to make a difference.

“Deformity is evil. Deformity is not permitted” is one of the hive rules and hatchlings that don’t measure up are swiftly dispatched. Flora is “obscenely ugly… excessively large” but is saved by a member of the ruling class, a Sage priestess, because “variation is not the same as deformity”, and is consequently able to transcend the caste system, her destiny changed forever. Intolerance runs through the hive, but in Flora’s case it is defeated. To what extent do humans live by a hive mentality, suspicious of outsiders and of non-conformity?

I can’t answer that, except to say that very little by very little, I do believe we are becoming a fairer, juster society. But there is still an intimidatingly huge amount of work to be done.

Hive rules dictate that only the Queen can lay the eggs, and early in the novel is a harrowing scene where you describe how rogue newborns are dealt with violently by the Fertility Police. Does this happen in actual hive society?

Yes, there really are little groups of bees who move around the hive searching (presumably by scent) for laying workers. And if and when they find the culprit and her issue, they will kill her and eat her eggs. It must be terrifying.

The forager bees ‘dancing’ the directions to prime pollen sites to the rest of the hive is an amazing strategy. What other extraordinary communication behaviours exist within the hive?

Scent is the bees’ language, both in what they take in and process, and the scents they can put out as signals to other bees. They do leave marker scent on their hive, as a homecoming beacon to foragers, and the Queen does produce a unique scent which keeps the hive calm and working well. Biologists readily acknowledge that they understand a tiny fraction of the scent-communication in the hive – which was great for me as a writer of fiction, because I could jump to intuitive conclusions, and make up the rationale afterwards. And the waggle dance is most definitely real, and very well documented. And the fact that the honeycomb transmits frequencies of buzzing, so much so that some biologists have likened it to the internet for the occupants, who can pick up information about tasks that need to be done, and who knows what other news, through their feet. It’s just incredible. So much so, I’m going to put three books at the end of this article, very accessible, very fascinating, that any reader intrigued to know more about the real science, might enjoy.

The power of love is another strong theme as we see Flora yearn for hive security and the Queen’s Love – and she herself has a nurturing instinct. Alongside the order, the brutality, the fear and violence, The Bees is essentially a quest for love, redemption and survival. What do you hope readers will take away from it?

I am truly delighted that already people are contacting me telling me how much more interested they are in the natural world, how they finished the book and then went to find out how much was based in the truth – a lot! – and how much pleasure it now gives them to watch bees. Someone blogged that she was no longer scared but fascinated by bees, and several people have told me they have caught and released bees in rooms, rather than squashing them to get rid of them. I wondered if following publication, my interest in bees would start to abate – but it hasn’t. I still get as much pleasure from watching them go about their business as I did when I was researching this book, and I think it’s going to stay with me. When you’re a child, your eyes are open to many wonders all around you, like the natural world, but as you get older, you forget how to look. If The Bees lets people see like that again, for a little while, that is a great reward to me.

The drones are lewd and revered like gods, and so unlike the demure but more powerful Sage priestesses. The battle of the sexes rages in one particularly dramatic scene with a grisly outcome for one side. Do you see a parallel in human society?

Ha! I really enjoyed writing both the drones and the priestesses, and I think the power of that scene comes from a real sense that if you hold back your real feelings and pretend, it’s only a matter of time before the truth will out. That scene you’re talking about is a rebellion against domination. And the release of huge resentment can have devastatingly destructive consequences.

“They say the season is deformed by rain, that the flowers shun us and fall unborn, that foragers are falling from the air and no one knows why”. The Bees alludes to environmental issues and the plight of the insect world – changing climate conditions; killer pesticides; the disruptive hand of Man – but you don’t overtly state it. Why did you hold back?

Because as Sam Goldwyn is supposed to have said, “If I wanted a message, I’d have sent a telegram.” I prefer books where the implication is clear, without a wagging finger. I’m not a biologist, nor a beekeeper, but I did my research and I drew my conclusions. I hope readers will do the same, and if they feel as I do, there are plenty of pressure groups and organisations that campaign against neonicotinoids being used in agriculture, and I’m sure Owen Paterson, Secretary of State for the Environment and MP for North Shropshire, would be interested in the increasing numbers of people who want him to legislate to curb their use.

You’ve created a new glossary with vivid associations. Do you imagine that terms like Flow, Sun Bell, Holy Chord, Hive Mind, and the rituals of The Kindness, the Royal Progress and Devotion could enter the vernacular?

I wouldn’t presume any more than to hope readers find The Bees a worthwhile experience.

What were your literary influences in shaping and writing The Bees?

So very many. I’m honoured and rather stunned that it’s been mentioned in the same breath as my literary heroes Margaret Atwood and George Orwell, and I can see why Richard Adams’ Watership Down has also been cited. I recently read the brilliant Horses of God by Mahi Binebine (Granta Books, translated from the French by Lulu Norman), and that reminded me of the political power of a good story. You tell the truth, and the flame jumps into the heart of the reader. Passionate writers of great craft are my inspiration, and the list would range from George Eliot to Tom Wolfe to Aldous Huxley to Elizabeth Smart to Chaucer to Geraldine Brooks to Cormac McCarthy and I could go on and on and come back with many more. But those spring to mind right now.

How much of an expert on honey bees were you prior to getting started on this book? How much research did you carry out on hive structure, bee biology and behaviour? Did learning more about bee life change your narrative? And how long did it take you to write the book?

No expert at all, I knew honey came from bees, but I wasn’t even sure if bumblebees made it too (they don’t). I did intensive full-time research for three or four months, until I reached a point where my ability to understand the statistics of higher biological research ran out, and I thought I’d probably taken in all I could, intellectually, and without becoming a beekeeper. Beekeepers, biologists, geneticists and botanists were very helpful and generous – even if some of them doubted I could pull off a whole novel set in a hive. And because there are so many stories to be told within the hive – you touched on it in your question about whose point of view I would tell it from – I had to be very disciplined about the structure of my story. In the end, every time there was a question about which way to go, I returned to the real biology of the hive as my spine, and that gives the narrative a lot of strength.

I wrote the book in a great rush, in case someone had already seen the brilliant potential of the story of the laying worker. I did the first draft in six weeks, and then an additional five drafts with some hefty revisions over the next 13 months. By the third draft I had my agent, by the fourth, my editor.

Could you say a little more about the publishing process and the reaction to your book within the industry, from literary agents to the pitch process?

A notable agent (who I chose not to go with in the end) told me on hearing my pitch before I’d written it: “Wow. Well you’ll either be able to pull it off and it will be the most brilliant book and a huge success, or you won’t be able to do it at all. For this, there’s no middle ground.” I held that comment close during the writing process, it was very useful. It made me determined.

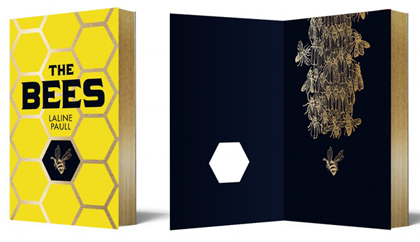

The book itself is an object of beauty. How involved were in the cover design?

Not at all! That is down to the skill and artistry of 4th Estate’s designer, Jo Walker. Thanks again Jo!

If you weren’t writing you’d be…?

Thinking about it.

What are you working on next?

A novel that excites me and scares me as much as my concept for The Bees. More than that I can’t say right now, except thank you for your interest in my work, and I hope you’ll come back for more.

Laline Paull was born in England, the daughter of first-generation Indian immigrants. She studied English at Oxford, screenwriting in Los Angeles, and theatre in London, and has had two plays performed at the Royal National Theatre. She is a member of BAFTA and the Writers’ Guild of America. She lives in England by the sea with her husband, the photographer Adrian Peacock, and their three children. The Bees is published by 4th Estate. Read more.

lalinepaull.com

Farhana Gani is a founding editor of Bookanista.

Follow her on Twitter: @farhanagani11

NON-FICTION BEE BOOKS

Readers who like The Bees might also enjoy:

The Biology of the Honeybee by Mark L. Winston (this is just brilliant)

Honeybee Democracy by Professor Thomas D. Seeley (the waggle dance and more)

Sweetness and Light: the Mysterious History of the Honey Bee by Hattie Ellis (a wide-ranging and entertaining overview)

LP