Landscape in winter

by John SpurlingThe times are turning bad again. I have been arrested for going to see a private art collection. Can you believe it? An old man of nearly eighty, a retired magistrate, is put in prison on suspicion. Instead of sitting on a dais giving judgment, here I am sitting on a stone floor waiting to be judged. Of course I’m only on remand. No one has tried or condemned me yet for the crime I am supposed to have committed, but still I’ve been here for weeks – long enough almost to have got used to the stench of the bucket in the corner. The jailer – a friendly man – says that the prisons are so full of people arrested on suspicion that it will take months, if not years, to sort out who is guilty and who is not.

Guilty of what? Conspiracy. Five years ago the Prime Minister was executed for conspiracy and anyone who ever had anything to do with him is still under suspicion. What did I have to do with such an important person? I went with some friends to look at his art collection. A rare privilege, as I thought, which turned out to be a curse.

I must not think of it as such. At my age one should be wiser and calmer. A man of my age has seen everything, done everything that he is ever likely to see or do. If he does not understand life as he nears the end of it, he never will. I have spent my life looking intensely at the so-called ‘ten thousand things’ that make up the world – man among them. I have constantly drawn them, thought and talked about them, drunk or sober, and they are not, in principle, difficult to understand. Life turns out to be much simpler than one imagines to start with, when one is young and everything is new and confusing. It is just a matter of following one’s nature, like a bird or a fish – in spite of such universal distractions as hunger, thirst, the urge to procreate, adversities and even disasters – always making, if one is a bird, for the thickest woods and if one is a fish for the deepest water.

Now suddenly, in my seventy-eighth year, chance, fate – whatever name one gives to something beyond one’s own control – has thrown me into prison for the first time. A fresh experience, yes, but does it invalidate all my previous experience, does it falsify my understanding of life? Why should it? I have seen plenty of people sent to prison, I have sent some of them there myself. It is one of the things that happen to people, that men do to one another, for good reasons or bad, and not essentially different from being ill or injured in an accident or losing everything one has. If it cannot be avoided, it must be accepted and one must try as always to follow one’s nature through it. This is the only wisdom I have acquired in a life lived through very troubled times and it would be folly, hysteria, and do no good at all to curse my luck. Better to bless my luck for bringing me to such an age without ever having been imprisoned before.

I can see the ironic side of it too: that I, for whom art has been my thickest woods and deepest water – the thing which sustained me through many difficulties, annoyances and sadnesses – should finally fall into a trap baited with art, like a fish or a bird caught by its own appetite.

Well, what can I do but continue to follow my nature and rely on art to lift me out of this hole? I shall revisit as much of my life as I can or care to remember, re-visualise it, re-imagine it. For although the principle of life is simple, its patterns of growth and survival and decay are complex. Every creature makes an individual pattern, human beings no less than fish or birds. But the clearest examples of this are plants, especially trees, whose patterns over time are, as it were, drawn on space. I shall try to see the pattern of my own life in the way I see a tree in a landscape and to look at myself as someone else. I shall be the scholar in the bottom corner of the painting who stands on a convenient crag and carries the viewer’s eye away from himself and into the landscape. But in this case I shall also be one of the landscape’s inhabitants. And so, as that person within the painting I shall experience time – life unfolding without knowledge of its future – but as this person on the crag, who has already passed through all that time, I shall experience it as a whole, as space, and perhaps perceive its pattern for the first time. Except, of course, for the relatively short time still to come when I shall have finished telling this story, viewing this landscape, when I shall turn away and go – where and how?

***

Since mountains and rivers normally change only over many centuries or millennia, we can safely say that from their point of view there was no story to tell about those two-and-a-half centuries when the Empire was ruled by foreigners.”

Rivers and mountains form the background to this story and from their perspective it is a straightforward one, except that in the eighty-fifth year of the Yuan Dynasty the Yellow River changed its course. This was a complication with important consequences for human beings, though perhaps it made no great difference to the Yellow River, which, seven years later, was re-channelled in its new course by an energetic Chancellor, a clever engineer, twenty thousand Mongol soldiers and a hundred and fifty thousand local peasants. That too had important consequences for the people of our Empire, but hardly for mountains, nor for the Yangzi River and the many smaller rivers to the south of it, where our story mostly happens, except that they had to carry away a lot of human blood and corpses. Rivers do that all the time during periods of bad government and make nothing of it.

Stories are about changes. Since mountains and rivers normally change only over many centuries or millennia, we can safely say that from their point of view – always excepting the unruly Yellow River – there was no story to tell about those two-and-a-half centuries when the Empire was ruled partly or wholly by foreigners, or even during the final two-and-a-half decades of anarchy and civil war when the Mongols were driven out and we recovered our freedom – or at least our independence. Yet those same mountains and rivers, whatever their own indifference, were both the setting for and the underlying cause of all the changes, since at bottom this is a simple story of landscape and its ownership.

We begin, then, in the eighty-fourth winter of Mongol occupation by taking ourselves south of the Yangzi River and letting our eyes slide down the flanks of a mountain. We notice a small stream, a clump of fir trees, a single one-storey house with a thatched roof, a group of similar houses partly concealed by pines, a fishing village away to the right and, immediately in front of us, a good-sized river, flowing swiftly but calmly over the rocky roots of the mountain. There are plenty of trees at this level: over there, on the far side of the river, is a wood of mountain oaks with the occasional rowan, all bare of leaves, their branches lightly dusted with snow. Snow lies also on the turf slopes above the riverbank and there are a few snowflakes in the air. If we raise our eyes again we can see the last grey wisps of the snow-cloud, but the sky above and around the mountain is blotted out by dense white vapour.

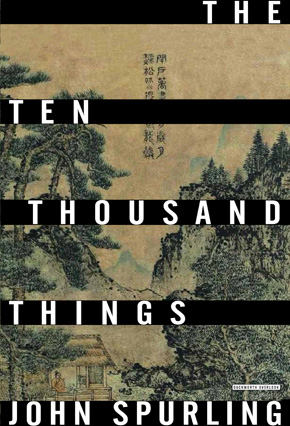

Writing Books under the Pine Trees, 1279–1368 by Wang Meng. Cleveland Museum of Art/Wikimedia Commons

Lowering our eyes once more to the far bank of the river, we can pick out among the trees the figure of a man with a large red sack over his shoulder. He wears a peasant’s wide-brimmed straw hat and grey-blue padded clothes and he is bent over, stooping to collect a fallen branch. He shakes the snow off it, breaks it into smaller pieces and drops them into his sack, then continues on his way to our left, disappearing behind trees, reappearing, stooping repeatedly, adding more sticks to his sack. On our side of the river, a fishing-boat is drawn into the bank and its owner, muffled and padded against the cold, crouches motionless in the bow, staring into the cloudy, rippled water. From the village in the distance there is the faint sound of a bell and a dog barking. Otherwise nothing moves or makes a sound, except for the river, a sudden scattering of disturbed crows and the man gathering firewood.

He is in sight of his home now, three or four thatched cabins on the far side of a little stream which flows out from under a covered balcony on the side of the house facing us and runs down into the river. He crosses a wooden footbridge, passes three tall pine trees standing together on the lawn in front of the house, stoops for a last stick, which he keeps in his hand, and disappears round the side of the house.

His family name is Wang, a common name, but although we have seen him collecting firewood like a peasant, he is not a common man. On his mother’s side he is descended from a famous general who rose to be Emperor and founded a long and successful dynasty. Wang even wears on the middle finger of his left hand a white jade ring, carved with dragons, which belonged to that fighting Emperor who two hundred years earlier healed and united the Empire after a previous period of civil war, chaos and foreign conquest.

Thirty-six years old, tall, usually slender and with a healthy complexion, Wang is at present pallid and overweight. He has spent too long in the city, poring over legal documents in an office, eating large meals and drinking too much with friends, taking too little exercise. Ever since he finished his education he has worked steadily and dutifully as a legal secretary in the local bureaucracy, earning enough for himself and his wife to live on, escaping from time to time in good weather to this country retreat under the Yellow Crane Mountain.

But what is he doing here in winter and why does a man of his age, ancestry and education not have a better job? Wang and his wife are at odds about this. He considers that he is kept down because the Mongol rulers favour their own people, whereas she points out that others in the family have become Governors of cities and suggests that if he showed sufficient ambition and drive or even simply made friends with the right people he would soon be promoted. Wang has responded angrily by resigning his post, leaving his wife in the city and coming to spend the winter alone in his country retreat. He is not, of course, quite alone. There are three local women cooking, cleaning and washing for him, there is a gardener-handyman and there is Deng, his young personal servant, who now meets him behind the house, takes his sack and is told to fetch tea.

The light is beginning to fade on this side of the mountain. Wang’s studio, the covered balcony which we have already noticed built on slender wooden piles over the little stream, is still clearly visible, but we can only dimly see Wang as he enters and sits down at a large table facing the view of lawn and riverbank. He has already changed his padded clothes for a loose robe. Now, as he contemplates the drawing on the table in front of him, he transforms himself mentally from a pseudo-peasant back into the gentleman-artist that he really is.

Deng enters with the little tray of tea and sets it on a corner of the table, well away from the sheet of clean paper with the new drawing begun that morning. Wang scarcely notices. He is already eager to correct and continue the drawing, which shows the three pine trees on his lawn, but wonders if the light is now too poor. However, the damp, dark texture of the bark excites him and, still staring at the trees, he feels for and picks up the inkstick with his right hand and finds the inkstone with his left. Deng, standing deferentially to his right, waiting to pour the tea for him but anxious not to disturb his master’s concentration, sees him suddenly start and stiffen and glance at his left hand with horror. The Emperor’s jade ring is missing.

From The Ten Thousand Things.

John Spurling is the author of the novels The Ragged End, After Zenda and A Book of Liszts. He is a prolific playwright, whose plays have been performed on television, radio and stage, including at the National Theatre, a frequent reviewer, and was for twelve years the art critic of the New Statesman. He lives in London and Arcadia, Greece, and is married to the biographer Hilary Spurling. The Ten Thousand Things is published in hardback by Duckworth. Read more.

John Spurling is the author of the novels The Ragged End, After Zenda and A Book of Liszts. He is a prolific playwright, whose plays have been performed on television, radio and stage, including at the National Theatre, a frequent reviewer, and was for twelve years the art critic of the New Statesman. He lives in London and Arcadia, Greece, and is married to the biographer Hilary Spurling. The Ten Thousand Things is published in hardback by Duckworth. Read more.

Author portrait © Nick Spurling

Wang Meng (c. 1308–85) is considered one of the four master-painters of the Yuan dynasty. Writing Books under the Pine Trees, 1279–1368 (above and cover) is a rare surviving example of the distinctive brush style for which he is renowned. It is signed and sealed at the left by the artist, who also wrote the following inscription in classical seal script (at the right):

Many years and months passed by the locked gate

Behind which the scholar has been immersed in writing his books;

While the pine trees he had planted

Have all grown up with old dragon scales.