Finding stories in America’s heartland

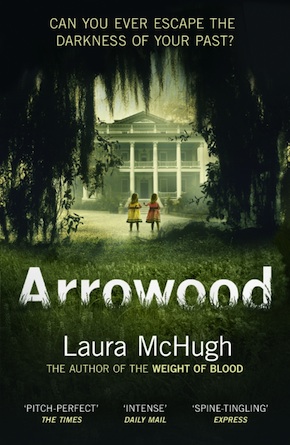

by Karin SalvalaggioIdeas come to writers in myriad ways. Anything is game, be it a newspaper article, an overheard conversation or a story passed down through a family for generations. The more open-ended the better, as it gives the writer more room to develop the story in their way. Novels may be based on the same ideas and themes, but like fingerprints, no two turn out the same. The more successful adaptations linger in our consciousness long after the we turn the last page. Arrowood, Laura McHugh’s brilliantly written second novel, is one such book.

Arden, Laura’s central character, returns home to the declining Iowa town of Keokuk, still bearing the weight of responsibility for her younger sisters’ abduction 20 years earlier. She was only 7 when the twins disappeared while in her care. The family home, which Arden has recently inherited, has housed generations of Arrowoods, many of whom have met tragic ends. It is a grand mansion situated on a bluff overlooking the Mississippi that Arden loves beyond all reason. Over her years of exile, she has “felt its absence like the ache of a poorly set bone.” Arden wants to reclaim the sprawling edifice, which is as imposing as ever, and make sense of her tragic past. It turns out her memories aren’t as reliable as she once thought. Finding the truth will force Arden to put many of her long-held misconceptions aside.

Laura McHugh writes with great fluency and a wonderful sense of place. Set in a town situated at the confluence of two rivers, the Des Moines and the Mississippi, water is a symbol that plays an important role in the narrative. McHugh’s reveals are never rushed. There is a languid, yet never dull, pace to this book that perfectly reflects the long history of the town and house where it’s set. Nothing in Keokuk and Arden’s family home happened overnight. This was a tragedy that developed over a long time. McHugh conjures up rich imagery at every turn of the page. I found myself reading passages again and again, earmarking them with coloured post-its for later consumption. Arrowood is a beautifully written novel, which I highly recommend. I look forward to seeing what Laura McHugh writes next. It was a pleasure to sit down to talk to her about her work.

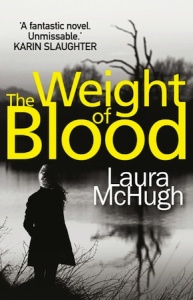

KS: Arrowood is set on the western banks of the Mississippi. Keokuk is a town emblematic of the decline of America’s heartland. The factories have shut down, jobs lost, shops boarded up, and into that vacuum God has entered in the form of mega churches. Arden Arrowood’s return is poignantly portrayed. It is through her eyes that we see and feel the full extent of Keokuk’s fall from grace. The scene where she visits ‘Sister House’, the repossessed home her relatives once owned, is both haunting and enlightening. People are still living amongst these small-town ruins. They may have survived the economy’s 2007 crash but the recovery that followed has left them far behind. In many ways, I felt your novel was a love letter to a lost America. In writing and researching Arrowood did you find some magic formula for saving these once-thriving communities? Could you also comment on what draws you to write about such settings? Your debut novel The Weight of Blood was also set in the small-town America.

I have no brilliant ideas for saving these forgotten places, but I will always seek ways to tell their stories.”

LM: I’ve lived in the Midwest nearly all my life, and over the years I’ve become both fascinated and deeply saddened by the decline of small towns across the region. When the jobs disappear, the population shrinks, but many people stay – some families have lived in the same place for generations and can’t fathom leaving – and the town decays around them. The rising desperation and the abandoned buildings provide a sense of unease and a rich setting for dark crime stories, though it goes deeper than that. There is something distinct and compelling about small-town life that draws me to set my novels there – the web of shared histories and secrets and loyalties, an interconnectedness that forces people to rely on each other and coexist with those who have hurt them. These towns might be dying, but people find a way to keep on living. I have no brilliant ideas for saving these forgotten places, but I will always seek ways to tell their stories.

LM: I’ve lived in the Midwest nearly all my life, and over the years I’ve become both fascinated and deeply saddened by the decline of small towns across the region. When the jobs disappear, the population shrinks, but many people stay – some families have lived in the same place for generations and can’t fathom leaving – and the town decays around them. The rising desperation and the abandoned buildings provide a sense of unease and a rich setting for dark crime stories, though it goes deeper than that. There is something distinct and compelling about small-town life that draws me to set my novels there – the web of shared histories and secrets and loyalties, an interconnectedness that forces people to rely on each other and coexist with those who have hurt them. These towns might be dying, but people find a way to keep on living. I have no brilliant ideas for saving these forgotten places, but I will always seek ways to tell their stories.

I’ve explored the theme of homecoming in many of my novels. It is a rich seam that is especially interesting in crime fiction as our memories aren’t necessarily reliable after so many years of absence. It has been 20 years since Arden’s twin sisters vanished, and the memories of that day are permanently etched in her mind. She soon learns that memory is ‘slippery’ and that the stories she’s been telling herself aren’t as reliable as she once thought. What research did you do with regards to false memory and development of memory in children in particular?

Memory and nostalgia have long fascinated me. As the youngest of eight children, I have many childhood memories that are probably not true memories, but imagined memories formed from the repetition of family stories. I remember watching our house burn down when I was barely two, smoke streaming out through the curtains, and it was only recently that it occurred to me that the memory was not my own. My grandparents had been with me, watching the house burn, and my grandmother had given me the image of the smoke and the curtains, recounting the story often enough that I held that vivid scene in my mind. I found it interesting that children can remember things from a very early age up until the age of eight, when those early memories inexplicably begin to disappear. Exceptions include events that have a major impact on the child, which can endure into adulthood. Arden was close to the age of memory loss when her sisters vanished, and their abduction left a lasting impression, though of course that memory, like all memories, was curated, coloured by the lens of childhood, and not necessarily perfect. I also read quite a bit about the notorious unreliability of eyewitness accounts – how several people can all witness the same scene and recall it differently moments later. I was interested in the ways that Arden’s eyewitness testimony affected the investigation into her sisters’ disappearance, and the process of unravelling memories in attempt to uncover the truth.

I remember watching our house burn down when I was barely two, smoke streaming out through the curtains, and it was only recently that it occurred to me that the memory was not my own.”

Your novel has some of the characteristics of a classic Gothic horror novel but never strays beyond the scope of the believable. Arden’s family home didn’t shrink with time. In Gothic horror the house where the novel is set often harbours its own secrets and, in the words of David De Vore, “not only evokes the atmosphere of horror and dread, but also portrays the deterioration of its world.” What Gothic novels have inspired your writing? I’m sensing that you might be a fellow Shirley Jackson fan...

We’ve Always Lived in the Castle is one of my all-time favourites! I love Shirley Jackson, and have always been a fan of books with creepy old houses. The real Keokuk is full of such places. I love the sense of history in these old homes, and can’t help imagining the stories of the people who used to live there. So often there are tragedies in a home’s past, hidden spaces, hints of ghost stories. My sister lives in a 19th-century mansion near the river, and she once encountered a rocking chair rocking on its own in her infant son’s room. That’s the sort of thing I enjoy in the Gothic vein – strange occurrences that might be easily explained away, but make you wonder, or shiver, nonetheless.

There was one scene in Arrowood that made me sit up and take notice, as it was so similar to something I wrote. My latest novel Silent Rain is set in a fictitious town in Montana. In the opening chapter Grace Adams dons a second-hand prom dress and runs drunk through the streets on Halloween night dressed as Carrie, and in Arrowood, Arden does almost the exact same thing. Given the number of novels being published, it isn’t surprising that there are parallels in storylines and even wording. But have you ever noticed such a strong similarity with another writer’s work before? What do you think it is about the character of Carrie that made us both want to dress our characters up as her for Halloween?

Wow! That is crazy. I have encountered instances like that as well, and while it can be jarring, it’s a good reminder that no matter how original our thoughts might be, someone else has probably come up with the same thing. Luckily, with publishing timelines and the staggering number of books out there, it’s usually clear that someone wrote their piece without ever having read the other. I could be wrong, but I feel like fiction writers aren’t eager to copy others – we tend to be proud of our creativity. I thought Carrie was a tragic figure that Arden could relate to – an outsider stepping out of her comfort zone to attend a party with a boy, hoping that it will go well and worrying that it might not. I also drew from personal experience; I dressed as Carrie for Halloween myself many years ago, buying the dress at Goodwill and standing in my tub to drench myself with fake blood. I quickly realised not everyone loved Carrie as much as I did – only a select few guessed who I was supposed to be, thus Arden’s pleasure when Josh immediately recognises her costume.

Is there something going on in the house, or is she driving herself mad obsessing over dripping faucets and humidity? I found water working its way into the narrative, and it was fun to incorporate.”

Water is a particularly important symbol in Arrowood. Arden is a Pisces who was born in a town on the banks of the Mississippi. She is “slippery, mutable, elusive; like a river… always moving and never getting anywhere.” The air in Keokuk is thick with humidity, faucets drip and bathrooms flood: “Water labouring through the ancient pipes… could trick you into hearing voices in the walls.” There are musty odours, mildew, and the windows appear to weep. You weave the symbol of water through the narrative, which is satisfying on many levels but I won’t go into in detail here as I don’t want to give too much of the plot away. Was the use of symbolism to bind the narrative something you’d thought of ahead of time or did it happen organically?

I began with the notion of her coming from this place at the convergence of two rivers, and always yearning to get back there. Is it possible that such a thing can mark you for life and have actual significance, or does she only imagine it? Similarly, is there something going on in the house, or is she driving herself mad obsessing over dripping faucets and humidity? I found water working its way into the narrative, and it was fun to incorporate, trying not to push it too far.

Hilary Mantel recently wrote a piece for the Guardian called ‘The Princess Myth: Hilary Mantel on Diana’. It wasn’t particularly complimentary but that’s beside the point. As the third daughter born to Viscount Althorp, Diana was possibly a ‘disappointment’ as their previous child, a son, had died within hours of his birth, and Diana’s parents were hoping for an heir but got stuck with Diana instead. She was six when her mother abandoned the young family and later her father remarried without first telling his children. Diana’s feelings of abandonment must have been intense. In the article Hilary Mantel introduces a theory posited by Jungian analyst Marion Woodman that “unwanted or superfluous children have difficulty in becoming embodied; they remain airy, available to fate, as if no one has signed them out of the soul store.” This could be a description of Arden Arrowood. The Jungian theory of the Death Mother is written about in detail online. Children rejected by their mothers (and fathers) can end up adrift. Arden’s relationship with her mother, who has remarried, is fraught with difficulty. She failed Arden and her sisters as children and continues to fail Arden as an adult. As a writer, what attracts you to these lost souls?

I follow true crime stories, especially missing persons cases, and I remember reading about a girl who saw her sister go off with someone, but she stayed behind, and her sister was later found murdered. I thought of this girl as I was writing Arden’s character. What must it feel like to be the one who stayed back? In Arden’s case, she was supposed to be watching her sisters, which compounded her guilt and cemented a lifelong obsession with her sisters’ disappearance that keeps her from moving forward in her own life. Your assessment of Arden is spot-on. Her parents’ neglect and disinterest, both before and after the girls’ disappearance, damaged her and left her adrift. I wondered how such a person would grow up and come to terms (or not) with her tragic past. What would it take for her to heal and move forward? Would it even be possible?

Finally, what are you working on next?

I’m working on edits for my third book, a mystery set in a rural farming community in the Midwest. It explores some of my favourite themes – blood ties, family secrets, and the dark side of small towns – and was partly inspired by the unexplained death of my brother.

Laura McHugh is the author of The Weight of Blood, which won both the 2015 International Thriller Writers award and a Silver Falchion award for best first novel, and was nominated for a Barry award and an Alex award. She spent part of her childhood in the town of Keokuk, Iowa, where Arrowood is set, and now lives in Columbia, Missouri, with her husband and two young children. Arrowood is published in paperback and eBook by Arrow.

Laura McHugh is the author of The Weight of Blood, which won both the 2015 International Thriller Writers award and a Silver Falchion award for best first novel, and was nominated for a Barry award and an Alex award. She spent part of her childhood in the town of Keokuk, Iowa, where Arrowood is set, and now lives in Columbia, Missouri, with her husband and two young children. Arrowood is published in paperback and eBook by Arrow.

Read more

weightofblood.com

@LauraSMcHugh

Karin Salvalaggio is the author of the Macy Greeley mystery novels Bone Dust White, Burnt River, Walleye Junction and Silent Rain and a contributing editor at Bookanista. She recently completed a new standalone thriller set in West London.

karinsalvalaggio.com

@KarinSalvala