Tania James: ‘Lion and Panther in London’

by Nikesh Shukla

“Surprising and affecting.” Romesh Gunesekera

Some short stories exist as fragments of time, giving you the middle of a moment, letting you figure out what brought people to that moment and what will become of them long after that fragment. Some short stories are static, in a head, in a simple interaction. If written badly, uncontrolled or imprecisely, these short stories can suck ass.

Tania James’ ‘Lion and Panther in London’ is the opposite of all of that. Laden with history, personal and of the time, it exists as record of the impact the British Empire has on the lives of its ‘subjects’, it explores the impact of fame and infamy on sibling relationships and it features descriptions of some badass wrestling.

We’re in London in 1910. The British Empire is at its peak. One of the Edwards is ruling so well, so memorably, the period gets named after him. Gama and Imam, two wrestling brothers, four years apart, are brought to London as a curiosity. They are pehliwans, experts in the malla-yuddha style, a type of wrestling (involving grappling, joint-breaking, pressure point-exploiting) that harks back to Mughal times. Brought over by a promoter to take on all wrestlers, boasting the ability to take on the entire country, Gama and Imam find themselves in stasis, in London, training in a suburban house, waiting for someone to take up the challenge. So far, no one has, and the promoter paying for their accommodation is frustrated, mostly with Gama whose integrity and lack of understanding of the pageantry of wrestling means he is unwilling to take a dive in “a city where athletes are actors, where the ring is a stage.”

Imam, regarded as the better wrestler technically, is his younger brother, sparring partner and translator, who watches from the sidelines as Gama goes from frustrated to talk of the town to star to a laughing stock in the newspapers. A slow realisation befalls the brothers – they could be at the top of their game but they will always be captive to the British Empire. As a commentator in the papers writes, “If the Indian wrestlers continue to win… their victories will spur on those dusky subjects who continue to menace the integrity of the British Empire.”

Tania James’ prose is controlled and unflowery enough to balance the small observations that place our brothers at the centre of history, ciphers for the circus-freak curiosity that greeted so many people under colonial rule. No matter what they did or however much their abilities were celebrated, they were still under the colonial yoke.

You can see the crowd, sweating, cheering, gasping, reviling, celebrating, chewing, spitting, drinking. You can hear the smack of double body weight on the mats. You can smell the blood, sweat and adrenaline in the air.”

The brilliance of the story is in its subversion of our expectations of stories concerning the British Empire. I think that’s why it speaks to me so much. I’m often frustrated by Britain’s obsession with period dramas, period comedies, revisionist obsessions with Austen and the Brontës and such, not because I don’t like the books, but because the amount of times those stories have been told and retold, made and remade for the screen, studied and pored over, means we rarely get to hear non-white stories, see non-white people and only regard the British Empire from a position of privilege. I worried, before reading this, that because period/historical fiction really sells, it meant that we would never see other stories. Reading ‘Lion and Panther in London’ changed that feeling. Not only did it give me hope for the wealth of material about the other, that challenged our vision of the British Empire by telling the stories of those beneath, but they could also be set in London. And without doing the ‘poor-me-poor-under-colonial-rule-me’ thing too.

Because there is all this badass wrestling in the story.

You can feel the clap of palm on bicep, the slap of flesh on flesh, the pull and push of joints and limbs as they contort, stretch and flex over each opponent. You can see the crowd, sweating, cheering, gasping, reviling, celebrating, chewing, spitting, drinking. You can hear the smack of double body weight on the mats. You can smell the blood, sweat and adrenaline in the air. “The second fall happens in but a blur – Doc laid out on his belly, sweat-slick and wincing at the spectators in the front row, who lean forward with their elbows on their knees.”

James covers a lot of ground. She covers Gama and Imam’s training (“Gama got to train at the akhara with Madho Singh, while Imam had to recite English poems about English flowers”). This balance of brothers, the yin and yang – while they are the same, they are ultimately different – Gama is stoic and focused, proud and prone to arrogance, while Imam is technically better than his brother in terms of holds, movements and strategy, but is sensitive and hero-worships Gama. The trip exposes the cracks in that hero-worship, because outside their comfort zone, and with Imam more in control of their environment through his understanding of English and his slow recognition of the nuances of English society, he becomes a stronger person. The tournament threatens to tear them apart. However, it is only when both seemingly get what they want that they reconnect. James’ ability to segue between the external and the internal while eschewing any sentimentality for these brothers, their abilities or the setting allows her to tell a story about a quiet unspoken sibling rivalry, about the realities of the British Empire, and about being in a strange world with only half an understanding of the rules that govern you.

It’s a brilliant story, told simply and without earnestness. It gives you everything you need – an understanding of brotherhood, a glimpse into a lasting period in history, and an insight into of turn-of-the-century pageant wrestling. And it’s called ‘Lion and Panther in London’. I mean that’s a badass name for a story.

Three badasses in one essay about short stories, not bad.

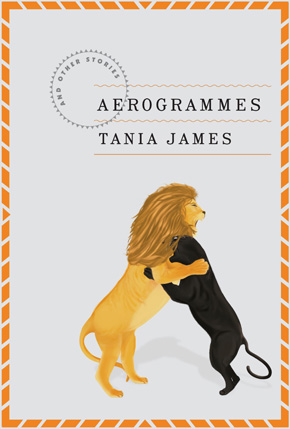

I picked the book this story appears in at Bombay airport, on the strength of the cover, a lion and a panther wrestling. When I saw the title of the story, I imagined something more literal – about a zoo escape. Instead I found something much richer, more real and more beautiful.

Tania James was raised in Louisville, Kentucky and lives with her husband and son in Washington, DC. She is the author of the novels Atlas of Unknowns (2009) and The Tusk That Did the Damage (2015) and the story collection Aerogrammes (Knopf, 2012; Vintage, 2013). ‘Lion and Panther in London’ is published in Aerogrammes, and also appeared in Granta 119: Britain (2012).

Tania James was raised in Louisville, Kentucky and lives with her husband and son in Washington, DC. She is the author of the novels Atlas of Unknowns (2009) and The Tusk That Did the Damage (2015) and the story collection Aerogrammes (Knopf, 2012; Vintage, 2013). ‘Lion and Panther in London’ is published in Aerogrammes, and also appeared in Granta 119: Britain (2012).

taniajames.com

@taniajam

Author portrait © Melissa Stewart Photography

Nikesh Shukla writes fiction and TV comedy. He is the author of the novels Coconut Unlimited (Quartet, 2010) and Meatspace (The Friday Project, 2014). His short stories have appeared in Best British Short Stories 2013, Five Dials, The Moth, Pen Pusher, The Sunday Times, on BBC Radio 4 and elsewhere.

Nikesh Shukla writes fiction and TV comedy. He is the author of the novels Coconut Unlimited (Quartet, 2010) and Meatspace (The Friday Project, 2014). His short stories have appeared in Best British Short Stories 2013, Five Dials, The Moth, Pen Pusher, The Sunday Times, on BBC Radio 4 and elsewhere.

nikesh-shukla.com

@nikeshshukla