Look to the skies

by Dawn Raffel

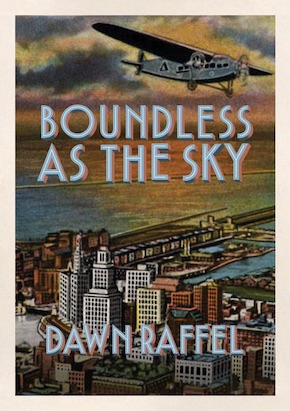

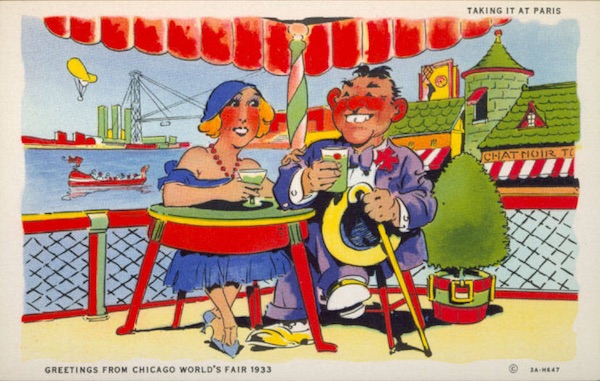

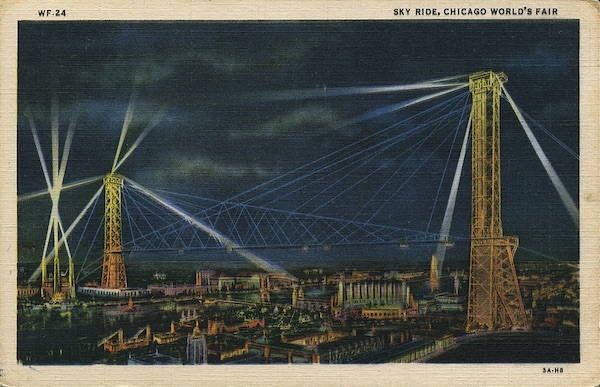

The novella Boundless as the Sky takes place in Chicago on a single day – 15 July, 1933. It is based closely on a true event, the arrival of a “roaring armada of goodwill” in the form of twenty-four seaplanes flown in a display of fascist power by Mussolini’s wingman Italo Balbo to Chicago’s Century of Progress World’s Fair. The 7,000-mile, seven-stop flight from Rome to Chicago was lauded by both Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Hitler, at a time when aviation made banner headlines across the US, and news of the Nazis was often in a side column. The novella follows a few of the many thousands of Chicagoans there to witness the planes’ arrival…

—

The world is full of pockets

[Name redacted], private, specialist

Today is a record, an unsurpassed feat, and it’s not even noon. The time in Chicago is 11:58 and twenty-six seconds. Twenty-seven. Twenty-eight, according to a fine gold timepiece known for its precision, a classic in design, which will never grow old, which he acquired in the course of a previous endeavor. It is even engraved. Rufus C. Dawes. The fair’s president. There are no coincidences, not in this life. Only tricky situations, in this case, involving the maid and a type of complication he would rather avoid, whereas this, this fair – this is cotton candy. This Century of Progress, this summer of abundance is a godsend if ever there was one. And mother of God, he is good at what he does. The barely perceptible jostle, the gentlemanly touch of the elbow, gallant, as if steadying a lady as she enters the Café de Alex, with its tablecloths and orchestra, the white-gloved sanctum for those who wish to dine among their kind whilst gracing the fair with their pedigreed presence, apart from the gristle and grease. The liberation is a miracle of elegance and grace. By the time she registers what is missing from her European purse, he is gone, a soul she never saw.

Out among the masses, awe is swell for business. The marching bands. The pageants. The Romance of a People, the story of the Jews, brought a fortune for him. And every day, the Great Hall of Science, revealing the very essence of life, the art exhibition with portraits by Whistler – transcendent! The Hall of Religion, with every conceivable path to salvation. The struggle of humanity to understand unanswerable questions, the reasons things happen, the meaning of events… Jesus. Zeus. And on the wall, the Promised Land, Moses included. A whole Mayan Temple erected for show. This is reverence for profit, so why not his? Did he not earn it? Did he not darken the earth with his blood and his spit in the trenches? Did he not witness his only little brother blown open to the bowels? It was the war to end wars, and how long will that last? Give it a minute till the whole bloody world is at it again, as best he can tell from that two-cent Trib. His mother mad with grief. His father dead of the Depression. Money. He will take what he can get.

Few of his marks, it is safe to conjecture, report their misfortune. This is a silent, private rebuke. Nobody likes to admit to being stupid, and anyway, what’s to be done?”

Hundreds of fools struck dumber than dumb each night in the dizzy “Streets of Paris” and the view is not bad. His act is unseen. He has the nimblest of fingers, the sharpest of eyes, a God-given talent. Imagine if she, oh faithless one, could see him now. Few of his marks, it is safe to conjecture, report their misfortune. This is a silent, private rebuke. Nobody likes to admit to being stupid, and anyway, what’s to be done? Tell a cop you were robbed but didn’t notice who did it?

Look at these dupes. The traveling salesmen, the housewives dragging their children through the cultural exhibits. The out-of-town lovers serenely believing they will never get caught. A couple of dollars, perhaps a missing necklace, is the least of their worries. It’s just an inconvenience, a valuable lesson. A service he performs, if you will.

All day long, the crowds are kept informed with loudspeaker announcements, this and that way to dispense with their money, a “free” demonstration, the lost-and-found youngster to please retrieve from Traveler’s Aid. And now, ladies and gentlemen, General Balbo’s arrival is – yes! – delayed, possibly later than late afternoon, the time is uncertain.

Not for him. The time is 12:04 and forty-six seconds. A donut is in order. Powdered sugar. And coffee. The crowds are growing thicker. And here is a boy who has just this very minute given the slip to his pretty older sister, who doesn’t seem bothered. Binoculars. Expensive. Money in the pocket, you can bet. But no, there are standards, morals he upholds. Children are off-limits.

—

The song is you

Tobias ‘Toby’ Weber, Jr., pianist, salesman (temperamentally unsuited)

The time he had given her, the time they had agreed upon, was one p.m. Did she misunderstand? Did he? He was early by almost a full half hour. Dozens, hundreds of people pass by, and none of them her. Strut, walk, saunter. Shuffle, limp, slouch. A torturous game he plays with himself: how many synonyms for walking? This one is practically skipping over here. Amble and stroll. Step, step, step. His heart is swiftly beating to a metronome of misery. A world of wrong answers: Young, old, decrepit. The drab and flabby middle. Hats. Shoes. Skin of every color from blue-black to pallor. A smattering of words, not all of them English. German he can understand, Italian he can’t, or maybe he can, a little. Ammazza! Syllables whose origins he can only guess. Polish? Hungarian? General Balbo is late in every language. And more to the point, so is she.

Constellations of girls, fat dandies swaggering past their prime, a trio of sausage-eating ladies who could have been his aunts and thank God they aren’t, he’d have to add lying to his list of sins. But where oh where is she? One-sixteen, according to the gentleman he has just asked. Why did he tell her the Homes of Tomorrow? There are twelve different homes. Is she lost? She frequently squints, he suspects she needs glasses; perhaps she can’t see him? Maybe he ought to move from this spot. But then what if she’s here and he’s there?

He pictures them flirting at the Black Forest Village, or watching that gal making ice cream from junket… Automated magic. There is even a robot that can smoke a cigarette.”

Last night it made sense, it sounded romantic: The Homes of Tomorrow. No one he knows will run into him here, at least he doesn’t think so. Does he? His sisters have already viewed this exhibit and chattered about it, prefabricated walls you can just stick together, one, two, three, a snap of a finger, and full of machines like the one that washes dishes, a miracle if ever there was one, if only they were rich, which they aren’t, but a person can dream. His father will wait in his store all day, praying for the chime that means a customer has entered, has stepped past the threshold. Every day the radio is playing – The White Sox when possible, customer favorites (if only there were customers): Vallee and Armstrong, Crosby, Astaire, and all this summer – live from the Century of Progress! – every kind of pageant and wonder, explained to the folks who cannot go. His father avoids the news that is disturbing. Better not to speak of it. And anyway, it wouldn’t please his customers (if only he had some). Already, it doesn’t help that he is German. People don’t like them, not since the war. But everybody likes to hear a radio, and anything is better than the silence of that smothering emporium of furnishings that nobody wants. Dark and unbudgeable dining room tables, sedate upholstered chairs. A sofa to lie down and die on. The future is sleek, its components interchangeable, but no, he won’t listen to his daughters or his wife, his piano-playing son. (My son is my son, but disappointing, Toby hears his father think.) And furthermore who will go shopping today? Today of all days? Half of the city – the half with any money – will be out at the lakefront. But even one sale is better than none, his father had said, while releasing his daughters from their weekly obligations (rearrange the toss pillows, slap out the dust, empty the ash trays, run a damp cloth, greet every person who walks through the door – assuming anyone does – as if they were family). So then it was clearly a matter of justice – Geh, wenn du must, go if you must – and anyway, it wasn’t as if, in his months of apprenticeship, he, Tobias Jr., putative heir, had sold much of anything. A couple of lamps choked in hideous fringe, a telephone stand for your granny. Dreary. Lugubrious. The home of the past. Speaking of which, his mother will spend all day in her kitchen, with her head in a cloud of aroma and heat. Strudel, sticky with molten apple sugar. Buttery nutmeats. A kingdom complete with its own weather system, impermeable; so that he, Toby, is safe from his mother’s appraisal.

Elsie, Anna, Greta – all three of his sisters are here at the fair, without any notion (he hopes!) of what he is up to. He pictures them flirting at the Black Forest Village, or watching that gal making ice cream from junket, or clapping for grain shot straight out of guns to make cereal for breakfast, not the sludgy porridge they were raised on. Automated magic. There is even a robot that can smoke a cigarette. Even better, in his sisters’ opinion, are the miniature babies in ovens, if they have enough quarters to see them again (and here he feels shame about what he has done). Greta, the youngest, lives for the paintings in the art exhibition, and she will point out that seeing them is free with the general admission, and maybe the others will indulge her, or not. Elsie will long for the Venetian glass that catches the light in every color, next door to the Italian Pavilion, which is going to be packed, impassable. Not one of his sisters cares about the airborne armada, as best he can tell, but history is happening, and later they can say they had seen it. Twenty-four seaplanes arriving in formation. Really, unless you are a pilot or Italian, how much does this matter? It doesn’t, to him.

His passion is music, flights of angels. A language any ear can understand, can receive at any time. Rachmaninoff. Tchaikovsky, Liszt, Brahms, Chopin. Beethoven. Wagner. A universe floating on a note, a world conjured with your fingers, even on the shabby old piano his mother had inherited, that poor wretched instrument of wood and warped fibers, the tusks of hunted elephants, the keys with which to enter the divine.

His passion is Dessie. Where is she?

—

A pleasant exchange

“Why, of course. I have one-thirty-one. And twenty-seven seconds. Twenty-eight, to be exact. Are you waiting for someone?”

—

Tempus fugit

Rufus Cutler Dawes, President, The Century of Progress, civic leader, visionary

Each and every time he looks at his wrist, he is displeased to see it’s bare. He has questioned the maid, who has been of no use. As for his wife, he would rather she be none the wiser; the watch was a gift, she is bound to be upset. There will be tears, recrimination. It is apt to turn up. It can’t have simply disappeared. It isn’t magic.

Meanwhile, the time is 2:38, according to the waiter at the Café de Alex, where, for the first time today he has a minute to himself (until someone interrupts him). Better to avoid the Officer’s Club, which is private, but not for him; he’ll be accosted nonstop (was this one or that one perhaps inadvertently left off the list for this evening’s events? As if it were he who has seen to these details.) At least he has a chance here, if only a small one, of not being bothered. The orchestra is playing Oscar Hammerstein, ‘The Song is You’. The lunch crowd has thinned.

Time is truly flying. And so, thank heaven, is General Balbo. The takeoff from Montreal was clean, if hours late, just before noon. Here on the ground, every last preparation is in order, every detail meticulously planned and observed from every angle in advance. The viewing stand for dignitaries, honorary speeches, the provisions for the press, the dinner at the Drake (and why don’t they pester Reed Landis; it’s he who’s in charge), and three more days packed full of receptions, including the photo with the Indian Chief, before the fleet takes off for New York, and he, Rufus Dawes, can breathe easy at last. The weather is perfect, hardly a cloud. He conferred with both Landis and Kelly an hour ago. There are men in black shirts and black ties who have gathered at the lakefront, but so far no sign of disturbance.

Still, there is uncertainty. According to intelligence, the fleet won’t arrive until close on to six, but no need to share that with everyone yet. The vendors are happy. The longer it takes, the better for business and this is important, if the Century of Progress is to realize a profit. Money and genius are coiled together, intertwined. The great Hall of Science! The whole of Fort Dearborn! The city’s reputation. So – to the people who said the Committee was crazy, staging this fair in the depths of the Depression – just look around. Millions of visitors, a blessing for Chicago, for the whole of the country. But nothing has been on a scale like today.

He should order something light. Not steak, which will cause indigestion again. He ought to save his appetite for tonight’s gala, Helen would tell him. She is getting ready, her hair is being done, whatever women do. He ought to reduce. But who can predict, for certain, what tonight will bring about? In fact, he deserves this. He earned it. Steak au poivre. Chicago beef, the French preparation. And potatoes au gratin. And a glass of red wine. Because you never know what the future will bring.

From Boundless as the Sky (Sagging Meniscus Press)

—

Dawn Raffel is a writer, developmental editor and creative writing teacher. Her previous book, The Strange Case of Dr. Couney, was chosen as one of NPR’s best books of 2018 and awarded a 2019 Christopher Award. Her other books include a memoir, The Secret Life of Objects; a novel, Carrying the Body; and two story collections, Further Adventures in the Restless Universe and In the Year of Long Division. Her stories have appeared in many magazines and anthologies, including NOON, BOMB, Conjunctions, Exquisite Pandemic, New American Writing, The Anchor Book of New American Short Stories, Best Small Fictions and more. Boundless as the Sky is published in paperback by Sagging Meniscus Press.

Read more

dawnraffel.com

@DawnRaffel

@saggingmeniscus

Author portrait © Claire Holt