Month-to-month loyalties

by TaraShea NesbitI cannot recall a specific moment in which I told myself that I would become a writer. But I know I was twenty, taking a bath in a crappy apartment in Columbus, Ohio, the first time I read something that made me feel the author was writing for me alone. I was reading Joan Didion’s ‘Goodbye to All That’, and I was covetous.

The essay appears to be the story of one woman falling out of love with a city she has idealised. I considered her techniques while also struggling to figure out exactly what premonition she was making about my own dreams. Would I move to New York and fail? Was she saying she missed her youth or that her perspective was more nuanced now? Oh, to be twenty and want so much for wisdom. The bath water grew cold and the bubbles formed a disappointing froth. I read ‘Goodbye to All That’ and thought: I want this. I wanted the silk yellow curtains blowing out the window:

All I ever did to that apartment was hang fifty yards of yellow theatrical silk across the bedroom windows, because I had some idea that the gold light would make me feel better, but I did not bother to weight the curtains correctly and all that summer the long panels of transparent golden silk would blow out the windows and get tangled and drenched in afternoon thunderstorms.

I wanted the curtains even if they did not make her feel better; they might make me feel better. I wanted the curtains and the skill to describe them. I wanted, even, the retrospective disillusionment, if it meant I could write.

I moved to New York a few years later, so that I could – I thought – be a real writer living in a real town. I would be moved by the city. But my New York was not Didion’s. My arrival in the city was greeted by my long-distance boyfriend and as the sun was setting, I climbed with him to the highest hill in Fort Greene Park and told him, simply but sheepishly, I think I might be gay. The fact that I had not acted on such desire, a distinction he repeated for the four hours it took before we finally turned in opposite directions, was the carnal energy that carried me through a hot, mostly lonely, broke, almost totally unconsummated summer. I wrote lyric poems about walking home from the subway and unrequited desire – none of these would, thankfully, make it to print. On Myrtle we parted in separate directions, I to a brownstone I was about to share with three recent Barnard graduates – a florist/model, an artist’s assistant/artist, and a gallery assistant/future gallery-owner – everyone had two titles: one that reflected how we paid our bills and one that indicated our aspiration. We had not yet failed.

I suspected Didion’s idea that one could rarely pinpoint the moment when “the heroine is no longer as optimistic as she once was” might be a prediction for my future. How sad, this infinity would end, I would go to New York and want to leave it, I would find writing to be a task, I would grow tired of being in a young person’s city, or worse, I would no longer be young.

But when I first read Didion’s essay, what I thought of most was how she made assertions only to refute them later, and so might I. The construction of her essays reflected the complexity and enigma of her content. She set it all up: In the first sentence of a paragraph I will make a direct statement. In the following sentences I will support that statement with my evidence. At the end I will suggest something else, or backtrack, or suggest an extension of that first sentence. And so, in the next paragraph, I will do it all over again, inch-worming my way to understanding. Somewhere a few paragraphs in I will question why I’m doing this, why I am asserting, asserting, and so I will speak to you, dear reader, and tell you I understand nothing. That it all meant nothing. But of course it did, she talked about it for many words, didn’t she?

If one wants to learn courage, they could first try being anonymous. I chased Didion’s early New York, and the anonymity of the city empowered me to cut my hair short, smile at women the way I thought I should only allow men to do to me, and later, be openly infatuated. But what does this all have to do with what influenced me to be a writer?

I fell in love not with people, but with sensation – admiring the sound and feel of warm rain and the tight comfort of closets as bedrooms and the stomach’s paucity of instant coffee on ice and peanut-butter sandwiches.”

That summer in New York I took a job selling test preparation for standardised tests. For nine hours a day I sat in a rotating set of grey cubicles one floor below the ever-envied Google Headquarters. In the break room, the flavoured coffee was vanilla, the television was turned to an argument of Telemundo (my favourite), CNN (the sales department’s favourite), and whatever sports game was on. Most people packed their lunch, and one woman ate no lunch at all, but sprawled the length of a lime couch and read Chuck Klosterman’s Sex, Drugs & Cocoa Puffs, holding the book to the sky, her head loose over the armrest, noticing no one. I told myself I would talk to this woman. And one day, I do not remember how, this woman and I began to talk. Soon we were eating Thai food in her apartment near Columbia, passing notes between cubicles, eating dinner at a sales manager/pastry chef’s apartment.

Joan Didion speaks of herself in third person, asking “Who is this heroine?” and, “Could anyone ever have been this young?” Partly because of what Didion records visually in her essay, I fell in love not with people, but with sensation – admiring the sound and feel of warm rain and the tight comfort of closets as bedrooms and the stomach’s paucity of instant coffee on ice and peanut-butter sandwiches.

I did not marry New York, or the woman. The problem was, I forgot in my haste, I had taken that job by lying. I had one year left of school in Saint Louis, but I had said I was finished with my Master’s. And the woman was a friend of my boss, so I could not tell her the truth. One evening, ever soon, I would confess that I was returning to Saint Louis, and I would leave. I was having a fling in which I was the only person that knew I was having a fling. Has anyone ever been this young?

I left New York and returned to Saint Louis and danced with young women that first night home and had a girlfriend by the week’s end. I left New York feeling that I was an asshole, leading this woman on, adoring her body at midnight and catching a plane at 5 am, a plane I had known all along I would be taking. But I was young, and there was all the time in the world to make a promise, break it, and be forgiven. My place in New York was temporary. My loyalties were month to month. Back then, when I was first becoming a writer, the only story I seemed to care about was my own.

Later, after moving to the West, after teaching Didion’s essay to undergraduate students, after marrying, after struggling to have a child, I would eventually come to love the latter half of ‘Goodbye to All That’, but that was much later. Readers get to the end of a Didion essay, exhausted, and conclude: “We knew it was time to go home” or “A coronet of seed pearls held her illusion veil” or, as in ‘Goodbye to All That’: “There were years I called Los Angeles ‘the coast’ but they seem a long time ago.”

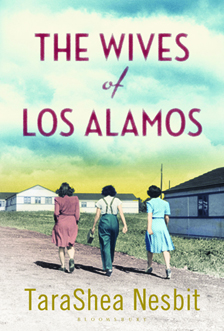

TaraShea Nesbit grew up in Dayton, Ohio, and lives in Boulder, Colorado. A graduate of the MFA program at Washington University in Saint Louis, she is currently pursuing a PhD in and teaching creative writing and literature at the University of Denver. She is the non-fiction editor of Better: Culture & Lit and her writing has been featured in the Iowa Review, Quarterly West and is forthcoming on NPR, in Necessary Fiction and elsewhere. Her debut novel The Wives of Los Alamos, about lives burdened by the creation of the atomic bomb, is published by Bloomsbury in hardback and eBook. Read more.

TaraShea Nesbit grew up in Dayton, Ohio, and lives in Boulder, Colorado. A graduate of the MFA program at Washington University in Saint Louis, she is currently pursuing a PhD in and teaching creative writing and literature at the University of Denver. She is the non-fiction editor of Better: Culture & Lit and her writing has been featured in the Iowa Review, Quarterly West and is forthcoming on NPR, in Necessary Fiction and elsewhere. Her debut novel The Wives of Los Alamos, about lives burdened by the creation of the atomic bomb, is published by Bloomsbury in hardback and eBook. Read more.

tarasheanesbit.com

Joan Didion‘s ‘Goodbye to All That’ was first published in the collection Slouching Towards Bethlehem, now available in an FSG Classics edition and in the Harper Perennial anthology Live and Learn.