Making sense of the past and present

by Anjum Hasan

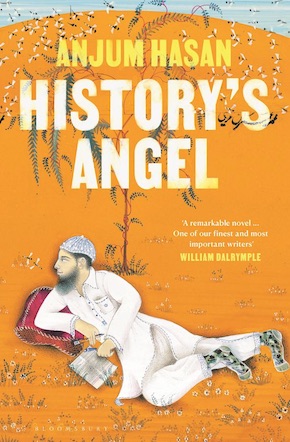

Anjum Hasan’s latest novel History’s Angel is an intimate portrait of contemporary Delhi seen through the eyes of a timid schoolteacher who is struggling to square his love of history with the questionable values, indifference and rising hostility that surround him as a Muslim in Narendra Modi’s India. She tells us about her motivations and inspirations.

Where are you now?

As I write this, in my mother’s apartment in Shillong. Got here yesterday for my annual visit, feeling monsoon melancholy listening to the rain clattering on tin roofs nearby. It’s 5,000 feet up and rain central.

Where and when do you do most of your writing?

I mostly write mornings in another hill town, also rain-drenched, called Madikeri. It’s where I live part of the time – a place where few novels are written or read and so ideal for going incognito. As well as facing up to the utter minuteness of what one does.

If you have one, what is your pre-writing ritual?

Writing down stray thoughts from the previous day. Sometimes just a few words. The other day the note said: Albert Camus’ ‘The Artist at Work’. Just something about my life at the moment, with a new book out, that made me recall this devastating cautionary tale about art and inspiration in the face of the ghastly societal demands on the artist.

How do you relax when you’re writing?

Alexander Technique. It’s a godsend.

How would you pitch your latest book in up to 25 words?

The pains and pleasures of ploughing lonely furrows in an era of great public pressures, the minor adventures of a Delhi schoolteacher obsessed with Indian history.

Naipaul said somewhere that those who cannot observe become obsessed with ideas. Alif is obsessed with ideas yet he doesn’t neglect to observe closely what’s going on around him.”

You’ve described the Delhi you depict in History’s Angel as a place “where joy in a new pair of shoes can override bad news politically, and where ambivalence is as strong a force as despair” and “none of us are either victims or oppressors in the comic book sense.” Could you elaborate?

Those things apply to the outlook in particular of Alif Mohammad, the novel’s hero. He tries to sidestep, literally, the maudlin attitudes to Indian history and how they’re used for political ends. Alif is someone who both takes the long view, as a historian, and the immediate one – by trying to immerse himself in everyday life. Naipaul said somewhere that those who cannot observe become obsessed with ideas. Alif is obsessed with ideas yet he doesn’t neglect to observe closely what’s going on around him.

The title is derived from an essay by Walter Benjamin about the perils of yearning for the past. What is Alif’s take on this?

The essay asks – how should we remember the past and how do we resist the stranglehold of the future? One could simply think linear, even as a historian, consider the past as an innocuous sequence of events. Benjamin asks if we need to do more – at moments of danger snatch up an image from the past, use it to fuel action against the oppressor.

What is the significance of setting the book in 2019, leading up to the Citizenship Amendment Act and subsequent protests?

So much was in the air that year – those protests against an act that was seen as weighed against Muslims, and their eventual suppression. But like much that is overtly political, this is in the background of the novel. Something seen on a TV screen, part of ongoing conversations. My central concern was with Alif – how would a bookish man respond to this moment of danger?

How would you summarise Narendra Modi’s take on Indian history, and his stand on ‘decolonisation’?

I’ll duck behind Alif’s take – he laments “that hunger for heroes that defines our vision of history – the past is nothing if not held up by proudly moustached men on horses, god-like men, even as the gods themselves are, given their grace and fallibility and moustaches, men-like.”

Which book/s do you treasure the most?

Those that I feel formed me, from The Bobbsey Twins to the novels of Saul Bellow.

Share with us your favourite line/s of dialogue, poetry or prose.

Those lines by Czeslaw Milosz, so much quoted but still capable of moving to tears:

What is poetry which does not save

Nations or people?

A connivance with official lies,

A song of drunkards whose throats will be cut in a moment,

Readings for sophomore girls.

That I wanted good poetry without knowing it,

That I discovered, late, its salutary aim,

In this and only this I find salvation.

‘Dedication’ (1945)

Which book/s have you most recently read and enjoyed?

Mitra Phukan’s The Collector’s Wife and Alaa Al Aswany’s Chicago.

What’s on your bedside table or e-reader?

I’m not the best at keeping up with new books though I do get to many of them in good time. But there is nothing like the pleasure of rereading the old – at the moment it’s A Passage to India and the very different Passage Through India.

Which books do you feel you ought to have read but haven’t yet?

Virginia Woolf’s novels.

What is the last work you read in translation?

The playwright and actor Girish Karnad’s wonderful autobiography This Life at Play in translation from Kannada.

Which story collections would you particularly recommend?

Yiyun Li’s Gold Boy, Emerald Girl; Budi Darma’s People from Bloomington, and Adam by S. Hareesh.

What are you working on next?

A history of the past and the present of the town I grew up in, Shillong. Trying to think here of history in the old sense when it was not very different from poetry.

Imagine you’re the host of a literary supper, who would your dinner guests be (living or dead, real or fictional)?

I prefer small gatherings to banquets. Turgenev has a lovely essay on what seems to him like a classic contrast between two contemporary characters – Don Quixote the idealist and Hamlet the individualist. So those two and to them I would add Woolf, the wise sisterly one, the one in whom thinking and doing seem combined.

If you weren’t writing you’d be…?

Teaching maybe. Both my parents were teachers and I seemed to be drifting that side but swerved away in my mid-20s.

On one of the walls in Alif’s classroom, in a child’s handwriting, is a faded quote from Rabindranath Tagore: “The highest education is that which does not merely give us information but makes our life in harmony with all existence.” What are your hopes for our being capable of making peace with our planet?

Bleak. We know it as theory and as, yes, information, but do we know and feel it as vision? The visions that compel most of us seem to be of a different order, not drawing on what the planet needs but what it doesn’t. I feel like E.M. Forster’s Adela. We ought to go back to the desert and start all over again.

If you were the last person on Earth, what would you write?

Reprise The Little Prince.

—

Anjum Hasan is the author of three novels and two short story collections, which have been shortlisted for the Indian Academy of Letters Prize, the Sahiya Akademi Award, the Hindu Best Fiction Award and the Crossword Fiction Award, as well as being longlisted for the Man Asia Literary Prize and the DSC Prize for South Asian Literature. Her short fiction and essays have appeared in Granta, The Paris Review, Los Angeles Review of Books, Literary Review, The Caravan and World Literature Today, among many others. History’s Angel is published by Bloomsbury in hardback and eBook.

Read more

anjumhasan.com

@BloomsburyBooks

Author photo by Lekha Naidu

Cover art: ‘Moderate Enlightenment’ by Imran Qureshi, 2007. Design by Mike Butcher