Memoir, social history and more

by Georgia de ChamberetMEMOIRS AND AUTOBIOGRAPHIES involving famous relatives are an intriguing read as they offer a backstage pass to history, combining private lives with public myth. After Oscar: The Legacy of a Scandal by Merlin Holland, Oscar Wilde’s only grandson, comes to mind. As does Two Flamboyant Fathers by Nicolette Devas. The daughter of Irish poet Francis Macnamara, Devas grew up, in part, in the bohemian household of the artist Augustus John. Her sister married Dylan Thomas.

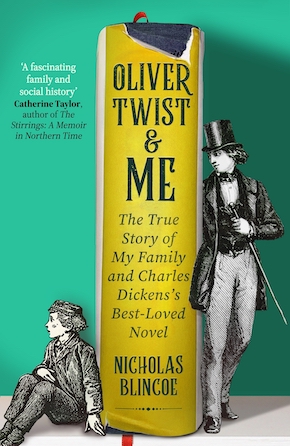

Nicholas Blincoe’s Oliver Twist & Me: The True Story of My Family and Charles Dickens’s Best-Loved Novel is a slightly different proposition. There are many biographies of Charles Dickens – by Forster, Johnson, Ackroyd, Tomalin, Slater, Douglas-Fairhurst – but this book stands apart, intertwining literary history with a personal journey. It is as much a memoir of family discovery as a work of social history and literary sleuthing.

“The television was tuned to the musical Oliver! [. . .] My father opened an eye and looked at the television. ‘Oliver Twist is a Blincoe,’ he said. ‘He’s my great-great-grandfather.”

Robert Blincoe (c. 1792-1860) was an orphan sent to the St Pancras workhouse aged four. Aged seven, he was indentured as a child apprentice in a cotton mill outside Nottingham, and went on to work in another mill in the Derbyshire peaks. The physical abuse done to Robert by various overseers was so horrific that his ears were mutilated, his hands were crooked, his stunted legs were knock-kneed and his “body was so bruised he looked like a leopard.”

His life of apprenticeship ended at twenty-one. Insecure, lonely and impoverished, in his late twenties Robert married a woman older than him, as “she will have him.” Settling down and working as a small businessman, “he remained an activist for working-class rights and industrial reform.” His story, dictated to John Brown, was published in 1828 under the title A Memoir of Robert Blincoe, an Orphan Boy. It is one of the earliest autobiographical accounts of the workhouse system and its impact on one of the many children whose labour powered industrial Britain.

The melding of fiction, memoir and history raises questions about the extent to which a novelist fuses the raw material of life with their fertile imagination.”

Nicholas Blincoe positions Robert’s life – as one of “the excess population reviled for their sins and exploited for their labour” – alongside Charles Dickens’ life, and his novel Oliver Twist, “the most loved, and the most enduring, of all of Dickens’ works.” By exploring whether the novelist drew on his great-great-great-grandfather’s memoir (and by extension the lived experience of countless workhouse children), Nicholas revisits canonical literature through a fresh angle. He also raises the question of how members of the working class become characters in literature written largely by middle-class writers.

Dickens may have been scarred by a rough childhood after he was sent to work in a bottling plant pasting labels on pots of blacking (polish used on shoes and fire grates), when his father was arrested for debt and sent to prison, but he was surrounded by aunts and uncles and did not suffer the isolation and physical torture meted out on Robert.

The relentless upheaval and transformation of the time, from the Peterloo Massacre and the rise of the Chartist movement, to the Reform Acts that expanded voting rights and redefined civic life, provide an illuminating backdrop. Poverty, institutional care and child exploitation persist today, though in far less brutal forms.

Nicholas Blincoe visits places central to his narrative, leading the reader on an actual walking tour of discovery, revealing glimpses of his own life along the way. He visits the mills outside Nottingham and in Buxton where his forebear had slaved; Charles Dickens’ Birthplace Museum in Portsmouth; Fleet Street, a hive of political dissent and literary experiment in the 1820s; and takes a weekend break on the Kent coast with his partner where Dickens went on holiday.

Alongside Balzac, Hugo, Zola and Dostoyevsky, Dickens was arguably part of a pan-European movement of social realism and outrage, each country producing its own mix of reformist indignation and artistic experiment. For literary commentators, the melding of fiction (Oliver Twist), memoir (Robert Blincoe) and history raises questions about the extent to which a novelist fuses the raw material of life with their fertile imagination, and what ultimately motivates them to write.

An award-winning novelist, Nicholas Blincoe brings narrative tension and a personal perspective to the historical material, making it engaging and compelling. His book considers how we inherit and perceive stories that are literary but also real, and what emerges when we dig into our own past. Although critics might quibble over the blend of memoir, fact and interpretation, I was absorbed by Oliver Twist & Me to the end.

—

Nicholas Blincoe is a bestselling, award-winning novelist, playwright and screenwriter and a critic and leader writer for the Daily Telegraph. Oliver Twist & Me is published by The Bridge Street Press in hardback and eBook.

Read more

instagram.com/olivertwistandme

@NicholasBlincoe

@LittleBrownUK

Georgia de Chamberet is an editor, translator and writer and the founder of BookBlast CIC. She hosts the BookBlast Translation Book Club on the second Monday of each month at Hatchards Piccadilly.

bookblast.org

instagram.com/bookblastofficial

bluesky @bookblast.org

X @bookblast

linktr.ee/bookblast

hatchards.co.uk/events