Memory’s martyr and keeper

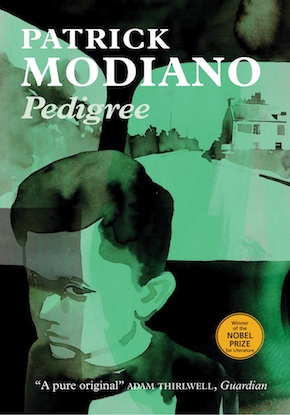

by Mika Provata-CarlonePatrick Modiano has often said that he is writing constantly, persistently, invariably but with almost infinite variations, the same book. And at the centre of each of his novels, almost like a reverberating echo or clinging shadow, is the story of himself in search “for mystery where there was none”, for the “transparency” (of memory, identity, history, reality) that he perceives as having stood like a parapet between him and life. In Pedigree Modiano decides to transcend the construct of hetero-autobiography and give an account of his existence before writing happened. An account that is as tensely explosive for the potency of its emotions, as it seeks to be glacially objective in timbre and impartiality of judgement.

We are meant to read Pedigree as an account of cultural heritage, historical legacy, family inheritance and personal lineage; with his weighty and highly ambiguous title, Modiano wants us to feel that a chronicle is about to unfold, a sequential narrative nurturing at its centre a solid tree of manifold branches and deep roots. Instead, he gives us a whirlwind of torn leaves, and within the eye of this ever-elusive maelstrom an almost unendurable loneliness, a trauma that will not heal.

The fabric starts to unravel from the very first pages, as Modiano recounts the periplous of his paternal grandfather from Salonica to Alexandria, then to Venezuela and Paris, where he will retain his Spanish citizenship and the passports of several nations. There are too many journeys and tangled roots severed haphazardly, too many occupations defining and alienating a name, a role in Modiano’s life that for all the surplus of determinants remains a spectral image. It is one of Modiano’s particular and oftentimes peculiar gifts to create a sense of momentum through ellipsis, through the casual referencing of both ordinary and extraordinary people, of circumstances and events. The reader is required to be in a constant state of vigilance – who has just walked on the page? What just happened? Unless these questions are the ever-present watchmen to the act of understanding and interpretation, we lose infinite layers of meaning, of history, of causality, which would in turn reduce Modiano’s novels to mere sophisticated fictional memoirs.

Modiano’s wealth is expressly this torrent of tantalising names, places and moments with their hinted legendary connections and lives, always remaining mute, obtuse, as though disappearing through quicksand. “Names end up becoming detached from the poor mortals who bore them and they glimmer in our imagination”, they are “scraps of life”, like the broken shards in an archaeological site or the shreds of a palimpsest from an ancient historiographer’s notebook. Reading Modiano’s novels requires digging deeper and piecing together, necessitates the consciousness of a duty: the duty of being, as he says in Dora Bruder, sentinels to memory, resisting the “sentinels of oblivion and forgetting” who are morally, historically and personally responsible for the disappearance of the past in our time.

The personal and the impersonal lose all boundaries in Modiano’s novels, underscoring the inextricable closeness and intimacy of memory.”

Memory and forgetting, memory and fear, absence and presence, the reeling sense of a void due to the denial of any access to a past, this centripetal need to be part of a historical and personal procession, and especially darkness, and the enigma of human personality and self-identity, are perhaps the motive principles behind all of Modiano’s writing. It was this “art of memory” that was recognised by the Swedish Academy, the literary gesture of remembrance that gave back life to unattainable destinies and to existence under the Nazi occupation. Also the gesture of ‘J’accuse’, whereby the fusion and melting together of identities transforms into a declaration of singularity, where the authorial I becomes every other life, as prefigured in his first novel La place de l’étoile, and exists as both unique and plural, past and present; where each hero’s conscience and sense of identity are almost liquid, atemporal, but very specifically historical, individual and distinct. We who live now, who were born after, are the “true recipients of the burden of the past”, he writes in Dora Bruder, and the occupation documents that come to light too late inevitably define our lives as “an expression of a sad gentleness and defiance”. If we are not there – if the writer is absent or inert – “there would be no trace of the presence of this stranger or of my father’s in a Black Maria in 1942.”

The personal and the impersonal lose all boundaries in Modiano’s novels, underscoring the inextricable closeness and intimacy of memory. We learn that his father’s Ford was impounded by the Vichy government and that it was in this car that Georges Mandel was assassinated. A name shot in the dark, quickly swept away into new oblivion, yet granted burning presence on the page for a few precious lines. A whole history behind that name, not readily recognisable by English readers, yet a history encapsulating the destiny and the alternatives for France at that moment in time. Similarly, the horrors of the Holocaust, of the normalisation of evil under the Nazis, is subtly yet sardonically conveyed by a single piece of information: von Ribbentrop had been a champagne salesman before the war…

His name Modiano, the family name of his father Alberto (Aldo), its echoes silenced and its connecting tendrils snipped, is one more link lost for him, a paradise perhaps that cannot be regained: Modianos were Modillanos as was Modigliani. They were Jews with long lines of rabbis, scholars, thriving communities and many ordinary lives.

Modiano’s working method, as he has said, is not to “immerse myself narcissistically into my childhood”. He does not “write in order to speak of myself or to try and understand myself. Nor do I write in order to reconstitute the facts. There is no desire for introspection.” He tells us that he was “simply marked during my childhood by an atmosphere, a climate, sometimes by situations, which I have used in order to write books. But always leaving behind the biographical level, in order to position myself on the level of the imagination, of poetry, with some events from my childhood as a matrix.”

In Pedigree it is difficult to always see this distinction, and the trauma from what is presented as parental neglect, indifference, dubious existence, leaves often an astringent aftertaste. “I am a dog who pretends to have a pedigree… there is nothing I can do about it. That’s the soil – or the dung – from which I emerged.” Modiano drifts and melts into a shadowland of loosely threaded recollections, some events looming more menacing than their particulars, the whole creating a feeling of wasting – but with a difference: there are books and encounters with artists, writers, exceptional or simply flamboyant individuals. There is the sense of what he calls the “penumbra” of his childhood in each of Modiano’s novels, especially in Dora Bruder, in So You Don’t Get Lost in the Neighbourhood or in The Black Notebook, but never as intransigent as here, in the Pedigree’s invective against a quagmire of youth and memory.

There is a strong Jane Eyre flavour and hue, culminating at the end of the novel in a Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man tone of defiance and sense of empowerment through the act of artistic (self-) creation. This is writing based on residual memory, diaries, the sense of a time and place, a writer’s gut instinct of what still needs to be said. On the basis of unrequited nostalgia and failed hope. Pedigree feels like a Pandora’s box full of plights stubbornly clinging inside, with hope long gone in a flash before it was even tasted. Modiano evokes here “our Joseph Roth”, whom J.M. Coetzee has called “the emperor of nostalgia” and elsewhere he has declared himself an admirer of the style of Paul Morand and Louis-Ferdinand Céline. Yet with Modiano it is the algos, the yearning pain, not the nostos (return) that dominates, or rather it is the nostos for a pain, a suffering and a shared memory of loss and endurance he was denied.

It is perhaps this denied pain that lies behind his incredible force of evoking shadows and dismembered memories. It is perhaps this denial of his place in a history and heritage of suffering and loss – but also of endurance, dignity, perseverance and even storytelling – that he feels is the greater act of cruelty, abandonment and neglect on his parents’, his father’s part. Modiano was born after the war, in 1945. His story is in many ways ‘wrong’, and it is this wrong narrative that he is trying to straighten with each novel. His father was a collaborator, a black marketeer, an intangible figure with a domineering power of influence on his early life. The repeated plea is for this man to speak – to explain both past and present, belonging and separation. It is perhaps Modiano’s greatest unpronounced accusation that his father denied him a place in a historical process, in a people’s history and tradition.

From this accusation arises a monumental writing project, a history of loss, since the archives of memory, his personal historical records, have been supressed, compromised, denied him. And from this sense of dislocation, the need for stronger ties, for a tribute to all that was real – and all that was past. Modiano uses writing as “the green pair of scales against the wall on the Terrasse du Bord de l’Eau” in order to weigh each individual life, its past and its future, its heaviness and lightness, its vacuum and purpose. From the infinite fragility and gaping wounds of a hazy past that he finds unbearable, he forges a framework of enquiry, a discernible background for language, for stories and existence. In Pedigree Modiano gives us the perspective of a child abandoned, his perception raw and undeveloped, absorbing the world without the means to assess it, process it, engage in it. This is his authorial subterfuge, his foil to tell not one but many stories. And especially the story of untold, untellable tales.

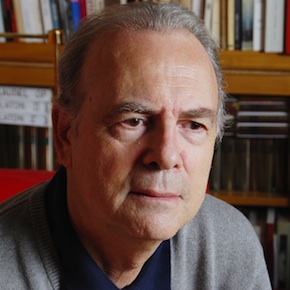

Patrick Modiano was born in Paris in 1945. The recipient of the 2014 Nobel Prize in Literature, he previously won the 2012 Austrian State Prize for European Literature, the 2010 Prix mondial Cino Del Duca from the Institut de France for lifetime achievement, the 1978 Prix Goncourt for Rue des boutiques obscures, and the 1972 Grand Prix du roman de l’Académie française for Les Boulevards de ceinture. Pedigree, translated by Mark Polizzotti, is published by MacLehose Press. Read more.

Patrick Modiano was born in Paris in 1945. The recipient of the 2014 Nobel Prize in Literature, he previously won the 2012 Austrian State Prize for European Literature, the 2010 Prix mondial Cino Del Duca from the Institut de France for lifetime achievement, the 1978 Prix Goncourt for Rue des boutiques obscures, and the 1972 Grand Prix du roman de l’Académie française for Les Boulevards de ceinture. Pedigree, translated by Mark Polizzotti, is published by MacLehose Press. Read more.

Author portrait © Catherine Hélie/Editions Gallimard

Mark Polizzotti is publisher and editor-in-chief at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the translator of over 30 books from the French, including works by Gustave Flaubert and Marguerite Duras.

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.