Sophisticated murder

by Peter Swanson

“An effective and compulsive thriller.” Washington Post

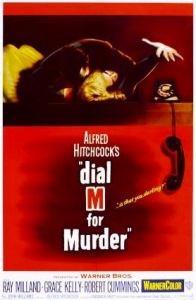

I was ten years old, living in England due to my father’s job transfer, when I first saw an Alfred Hitchcock film. That film was Dial M for Murder, Hitchcock’s 1954 adaptation of Frederick Knott’s stage play. If I were introducing the films of Alfred Hitchcock to a ten-year-old boy, Dial M for Murder would be close to the bottom of the list. The Thirty-Nine Steps comes to mind as ideal, or maybe its direct descendent North by Northwest. Both are chase films, filled with action set-pieces and literal cliffhangers. Dial M for Murder takes place entirely in a London flat, and except for one botched murder attempt, is all talk, all the time. Despite this, I was one smitten ten-year-old when I saw the film. It began a lifelong love affair not just with Alfred Hitchcock films, but with films in which darkness lurks just beneath the veneer of civilised society.

I’d heard of Alfred Hitchcock before seeing Dial M for Murder. This was due to a record album called Alfred Hitchcock Presents Ghost Stories for Young People. My sister and I had played and re-played that album, challenging one another to listen to it in the dark enclosure of a mini-attic we’d turned into a playroom. The stories were for kids, but they were creepy, some of them getting under my skin. People sometimes think that because I write scary, gruesome, stories that I’m immune to that stuff. But I think the opposite is true; horror writers and thriller writers can’t get the bad stuff out of their heads, so they try and write it away.

Too many movies and novels in the thriller genre bludgeon their audience with an accumulation of shocking scenes. But it works much better when there is less.”

The tame ghost stories on the Alfred Hitchcock children’s album only prepared me for Dial M for Murder in the sense that I knew the movie was supposed to be frightening. The “Murder” in the title gave that away as well. The film begins slowly; retired tennis player Tony Wendice (the sublime Ray Milland) offering drinks to his socialite wife Margo (Grace Kelly), and a visiting American writer named Mark Halliday (Robert Cummings). Later we learn that Margot has had an affair with Mark, and that Tony knows about it. He has a plan to murder his wife, both for purposes of revenge, and to get his hands on her money.

amazon.co.uk: audio download” width=”170″ height=”170″>The first thing that fascinated the ten-year-old me when watching this movie was how the bad guy in the film, dapper, upper-crust Tony Wendice, was indistinguishable from the good guys, e.g. the dapper, upper-crust police inspector played by Hitchcock favorite John Williams. I was used to villains who telegraphed their villainy. Darth Vader. The Joker. Basil Rathbone in The Adventures of Robin Hood. Ray Milland plays Tony as a slightly aggrieved husband arranging his wife’s death the way he might arrange a trip to the south of France. He’s calm, charming, unfailingly polite. At the end of the film, when he’s been caught out by the police, he doesn’t lunge for a knife, and try to fight his way out of it. He sidles to the drinks table and pours himself a whiskey, offering drinks to others in the room.

amazon.co.uk: audio download” width=”170″ height=”170″>The first thing that fascinated the ten-year-old me when watching this movie was how the bad guy in the film, dapper, upper-crust Tony Wendice, was indistinguishable from the good guys, e.g. the dapper, upper-crust police inspector played by Hitchcock favorite John Williams. I was used to villains who telegraphed their villainy. Darth Vader. The Joker. Basil Rathbone in The Adventures of Robin Hood. Ray Milland plays Tony as a slightly aggrieved husband arranging his wife’s death the way he might arrange a trip to the south of France. He’s calm, charming, unfailingly polite. At the end of the film, when he’s been caught out by the police, he doesn’t lunge for a knife, and try to fight his way out of it. He sidles to the drinks table and pours himself a whiskey, offering drinks to others in the room.

This kind of new villain both unnerved me and thrilled me. Tony Wendice was evil (it was Grace Kelly whose pretty neck he’d hired someone to strangle, after all) and remorseless, but he satisfied all the adult requirements of civilised society. Handsome, in a well-cut suit; someone who could almost pass as James Bond. This made his villainy that much creepier to me; it was hidden. Since then I’ve always been drawn to villains that could hide in plain sight. I like them in the books I read, and the movies I watch, and I like to create them in the novels I write.

I’ve since seen every film Alfred Hitchcock directed (yes, even Topaz), and now know that Dial M for Murder was one of four Hitchcock pictures in which he experimented with confined space. He’d already made Lifeboat, a drama that unfolds among the survivors of two sunken vessels sharing one small lifeboat, and Rope, that takes place in real time in one New York apartment during a cocktail party. After Dial M for Murder, Hitchcock would make his most famous single-location movie, Rear Window. What I like, and take, from all of these films, is the idea that mystery narratives do not need to be complex to generate suspense. There is an economy to Dial M for Murder; what makes it work is the dialogue, and a great mid-film twist that turns the narrative around. That, and the brilliant camerawork employed by Hitchcock to make the single location setting work.

Although the film plays out mostly through dialogue and the limited movement of its cast, there is one justifiably famous bit of mayhem in the middle of the film. The man who has been blackmailed by Tony Wendice to kill his wife is stabbed with a pair of scissors instead. It’s a grisly murder; he struggles to reach the knife but it’s like an infuriating itch you can’t quite get to, then he collapses, landing on the scissors. There is a close-up of the scissors sinking further into his back. As a ten-year-old I was, of course, semi-traumatised (not that I stopped watching). The impact of the scene was Hitchcock’s perverse attention to detail, but it was also impactful because it’s the only scene like it in the film.

Although the film plays out mostly through dialogue and the limited movement of its cast, there is one justifiably famous bit of mayhem in the middle of the film. The man who has been blackmailed by Tony Wendice to kill his wife is stabbed with a pair of scissors instead. It’s a grisly murder; he struggles to reach the knife but it’s like an infuriating itch you can’t quite get to, then he collapses, landing on the scissors. There is a close-up of the scissors sinking further into his back. As a ten-year-old I was, of course, semi-traumatised (not that I stopped watching). The impact of the scene was Hitchcock’s perverse attention to detail, but it was also impactful because it’s the only scene like it in the film.

Too many movies and novels in the thriller genre bludgeon their audience with an accumulation of shocking scenes. But it works much better when there is less. That’s what I took away from Dial M for Murder. Thrillers don’t need to be constantly thrilling. Villains don’t need to twirl their moustache, or stroke white cats. Thrillers work because we are brought into a familiar world, large or small, and told that the rules will no longer apply.

That one film at a young age led me to my favourite genre. It also led me to believe, incorrectly, that adult life was an unending stream of cocktail parties and drink trays and men in suits, and women who looked like Grace Kelly. And that underneath all that civility, all hell might break loose. It didn’t turn out that way, but it did give me a blueprint for what I’m trying to achieve with my own books. An ordinary setting and an extraordinary story.

Peter Swanson‘s debut novel, The Girl with a Clock for a Heart (2014), was described by Dennis Lehane as “a twisty, sexy, electric thrill ride” and was nominated for the LA Times book award. His follow up The Kind Worth Killing (2015), a Richard and Judy pick, was shortlisted for the Ian Fleming Silver Dagger, named the iBook stores Thriller of the Year and a top ten paperback bestseller. A graduate of Trinity College, the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, and Emerson College, he lives with his wife and cat in Somerville, Massachusetts. His third novel Her Every Fear is out now from Faber & Faber.

Peter Swanson‘s debut novel, The Girl with a Clock for a Heart (2014), was described by Dennis Lehane as “a twisty, sexy, electric thrill ride” and was nominated for the LA Times book award. His follow up The Kind Worth Killing (2015), a Richard and Judy pick, was shortlisted for the Ian Fleming Silver Dagger, named the iBook stores Thriller of the Year and a top ten paperback bestseller. A graduate of Trinity College, the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, and Emerson College, he lives with his wife and cat in Somerville, Massachusetts. His third novel Her Every Fear is out now from Faber & Faber.

Read more.

peter-swanson.com

@PeterSwanson3