My grandmother

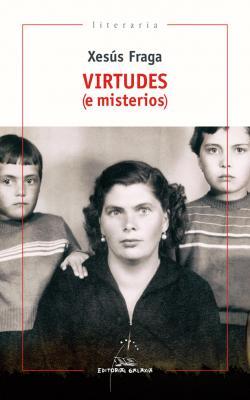

by Xesús FragaWith some frequency, we hear readers ask authors how much of their novels they’ve pulled from their own lives, assuming that some if not most of the content must be autobiographical. One of the fascinating things about this memoir by Xesús Fraga is that readers ask the same thing, because it seems simply impossible that this magnificent work of literature could possibly be anything but a novel. In part, I’m sure this has to do with his portrayal of his grandmother, a larger-than-life force of nature, who he gives such depth, pathos, hilarity and personality that readers must assume he’s made her up. But what makes Virtues (and Mysteries) – the title is a play on his grandmother’s name, Virtudes, (‘virtues’) – so uniquely brilliant is how it takes the raw material of an utterly commonplace story – Galician poverty, emigration, and in many cases, disappearance – and moulds it into a universal tale of struggle and sacrifice. Very few Galician-language books have won Spain’s National Narrative Prize; it comes as no surprise that this did just that in 2021.

Jacob Rogers

—

ANYTIME MY GRANDMOTHER got angry, her eyes would flash with a feral gleam, and she would clench her teeth in a grim rictus, lips pursed, jaw quaking. She reminded me, in these moments, of a bulldog sniffing out your slightest weakness, your slightest misstep. She would crouch into a squat and eye you from this low vantage point, which, rather than undermine her authority, was a clear sign she was primed to attack. When my grandmother got angry with me specifically, it was almost always because I’d either questioned her infallible opinions, or because some problem had arisen which (according to her) was my fault, but which (from my perspective) was purely a misunderstanding. She didn’t care what I had to say, batting away my defences with an unmatchable argument:

“Estás wrong!”

The angriest she’s ever been with me, the nearest I’ve ever felt the bulldog’s fangs to my face, was one morning outside her flat in London. We were on our way to the airport to catch a flight to Galicia and had lugged our suitcases down to the vestibule. “I’m going to see if I can find a taxi at High Street Kensington. You stay here with our things,” she had ordained, before opening the door and descending the steps down to the pavement, still deserted and lit by the feeble yellow of the street-lamps at these early hours of the morning. Watching her walk in the direction of the faint murmur of traffic from the main road, I felt a sudden, irrepressible urge to follow her. To this day, I still don’t know why I acted on it; maybe it was an impulsive, childish fear of being left alone. Whatever the case, I rushed down the five steps separating the pavement from her front door, which I’d made sure to shut, I guess out of some instinct not to leave our belongings unattended.

‘Wait, I’m coming with you!’

My grandmother had already set off walking and didn’t hear me. I nearly had to run to catch up. She couldn’t have been more incredulous when she saw me.

‘What are you doing here? What if someone shuts the door? Didn’t you see I left my keys back with my purse?’

I confessed that the door had already been shut, though I neglected to mention that I was the culprit. Predictably, her incredulity turned to rage, followed by a litany of vehement curses, which I immediately set to work repressing. Any attempt to reproduce them here would be an exercise in memory, and exercises in memory are always more of a reinvention than a retelling, and anyway, I’d never be able to do the experience justice. Things weren’t looking good for us, stuck outside my grandmother’s building at four in the morning with no key and all our bags inside. The only bright spot was that, thanks to my grandmother’s perennial insistence on arriving three or four hours before take-off, we still had loads of time.

As was her custom, as soon as my grandmother had finished discharging her anger, she solved the problem. She rang the bell for the housekeepo, as she called the housekeeper who lived in the street-level flat. After a few minutes, he finally peeked his black face grumpily out from behind the curtains. He was even grumpier when he came out and opened the front door, returning us to the security of the vestibule and the relieving sight of our luggage; I let out a silent sigh of relief while my grandmother placated him with a self-interested (albeit accurate) version of events:

“My grandson! He go outside with no keys! And closed the door! He is stupid! Crazy! Stupid!”

Have I mentioned yet that this is an exercise in memory?

How odd her expressions sounded to our young ears; having grown up in a predominantly Spanish-speaking milieu, we couldn’t help but be simultaneously fascinated and amused by her old-fashioned-sounding Galician.”

These castigations were but one of the many and varied manifestations of my grandmother’s famous temper. If you showed any signs of lollygagging, or simply couldn’t keep up with her, she would unleash the full force of her wrath upon you, no exceptions.

“Chop, chop, María Isabel!” she once shouted at my mother, who had fallen behind with the heavy shopping bags, and this teasing command even made its way into our family lexicon. We found it funny to see these rare displays of maternalism in my grandmother – hidden by her living abroad and by the inflexible, impatient shell the self-sacrificial tend to armour themselves with – and it was undeniably tickling to see my mother briefly turned into the docile child she hadn’t been for a long time, ever since circumstances had forced her to become a mother not just to herself, but also to her two young sisters. Of course, that was long before I was born.

Another part of the humour, for us, was in how odd her expressions sounded to our young ears; having grown up in a predominantly Spanish-speaking milieu, we couldn’t help but be simultaneously fascinated and amused by her old-fashioned-sounding Galician.

‘These nuts are balorecidas,’ she once said, for example. My cousins and I, who had never in our lives heard the word balorecidas used to indicate mouldiness, burst into peals of laughter.

And then there was her repertoire of composite words. Between her vehemence and our never having heard these words before, we always assumed she’d simply made them up.

‘You’ve got to esmachucalo,’ she would say, doubling the impact that the Galician ‘esmagar’ or the Spanish ‘machucar’ (to crush, in both cases) would have had on their own.

Not to mention the ferocious refrains that left us equally tittering and terrified:

‘God knows what came over that woman, walking around like a whore at Lent!’

Twenty-five years in London – which she was already well into by the time we were kids – hadn’t stopped a certain understratum of her formerly rural life from cropping up occasionally in her speech, and she still used old phrases from back then (“It’s like Korea out here!” she would say as a catchall for a negative sort of surprise), which reinforced her natural expressiveness. Her phonetic adaptations of place names in the British capital – Édua (Edgware) Road, or Jaimesmí (Hammersmith) – also coloured her British Galician, but nothing was as liable to send us into an uncontrollable fit of laughter as her awe-inspiring, high-powered collision of curse words:

‘Fockin’ merda!’

But this didn’t mean my grandmother couldn’t be infected by our laughter, which she would cut short with another famous phrase:

“Quiet, quiet, I’m going to pee myself!”

Virtudes transformed in London and became Betty, two separate women inhabiting the same body. She didn’t look different either way, but depending on the context, one of the two was always at the helm.”

This linguistic cohabitation was the outward embodiment of her twin nature: the merger of the girl who’d turned fifteen in nineteen thirty-nine (the year the Civil War ended) and who’d never known anything but rural life with work in the fields or as a servant, with the woman who had emigrated to a sprawling, unfamiliar metropolis. Virtudes transformed in London and became Betty, two separate women inhabiting the same body. She didn’t look different either way, but depending on the context, one of the two was always at the helm. When she tied a scarf around her head and bent over to gather potatoes or cut bunches of grapes off the vine, she looked like any other grandmother playing the role that her rural upbringing had trained her to, a way of life that was losing its hold but still maintained its grasp within family settings. Yet no one who saw her slit a rabbit’s throat would have guessed that, only hours before, she had used those same hands to iron wrinkles out of the silk garments entrusted to her by the residents of London’s wealthiest postal codes. Nor would anyone have taken particular notice of the pensioner in the anonymous raincoat and comfy sandals, hunting for bargains among the stalls at the Friday market on Edgware Road, or the Sunday market at Earl’s Court. She would haggle over prices with all the vendors, be they English or Syrian, Greek or Italian, exactly as she might have in Betanzos. Their eyes would go wide and they’d chuckle to themselves when, as soon as they had settled on a price with this cunning old woman, she would reach coolly through the neck of her blouse and remove a neat wad of bills from a sack that she had safety-pinned to her salmon-coloured bra.

The markets – these were the true purpose to her decades of working and living alone in London. It was at the markets that she fully realized her role as the breadwinning emigrant, a role she was loath to give up even after times had changed and we were no longer in such dire financial straits. The pounds she folded into that money-sack provided for her three daughters and her mother, who took care of the girls in my grandmother’s absence. Not only had she been able to provide them a roof of their own (quite the achievement for someone from a social class that had known nothing but poverty during the endless years of post-war austerity), she also earned enough for them to live a comfortable, and more importantly, dignified life. From London she sent them beds, sheets, and their first comforters, along with fabric for dresses, linen for suits, footwear, affordable jewellery and accessories, dining-ware, tea sets, pots and pans, and books and magazines which contained images of a freer, more modern world, like the early full-page spreads of The Beatles, which longer exist except in the memory of my mother, her sisters and their cousins.

Larger packages were shipped to Betanzos through transport companies specializing in emigrant remittances. Once they’d arrived at the listed address, the packages had to be redistributed according to my grandmother’s handwritten instructions and conveyed from their destination to whichever relative’s name had popped into her head while her trained eyes scanned the market stalls: a Scottish wool skirt for Isabel, who was always cold, a short coat for Leonor, a pair of shoes for Elena, and towels or sheets for her mother. The smaller packages had to wait until she returned for Christmas or for summer vacation. Some summers, I would travel back to Galicia with her. The most important thing about this was that it meant she could pack twice as much.

One, or even two or three days before our departure, she would spend an entire afternoon contemplating our open suitcases on the bed like a blank puzzle and would proceed to stuff in as many of the items she had been accumulating since January (or earlier, if there was anything she hadn’t been able to bring at Christmas) as she could. On my way to London, I always had strict instructions to pack as light as possible. As far as my grandmother was concerned, that meant a single change of clothes, or not even that. But she knew I could never come with so little. Our acquaintances in Betanzos would take advantage of my trips to send along presents for their emigrated relatives: usually a Galician cheese, or a string of chourizo, or, less frequently, a bottle of homemade moonshine, which put me in some tricky situations at customs. As soon as I’d arrived, we would begin the ritual that involved going from house to house to deliver the presents and pay a visit to fellow Galicians, but what we were really doing was moving closer to my grandmother’s true goal: the total emptiness of my suitcase.

After many hard decisions about what we would bring and what would have to wait until the next trip, after many struggles with the limited dimensions of our suitcases and hand luggage, we faced the long, gruelling task of closing the zippers. But that wasn’t the final test. There was still the scale, into whose judgement we would place the fruits of our painstaking labour. We would heave our suitcases onto my grandmother’s bathroom scale (the kind with a needle), orienting them this way, then that – equal volume, various measurements, and one common denominator: they were eye-poppingly overweight. Back then, you were allowed to check forty pounds, because most people’s luggage weighed forty-five. Ours usually fell somewhere in the fifty-pound range, sometimes reaching as high as sixty or more. Between the two of us, we were liable to show up at the check-in counter with a combined total of one hundred and fifty or sixty pounds of luggage, which we would have to divide between as many cabin bags as we possibly could. Under my arm, I might have carried between forty to fifty pounds of vinyl records, tightly wrapped in bags from shops where I’d bought them; my grandmother may have been a master of the markets, but I was an expert at finding bootlegs of The Clash, rare reggae gems and treasures in fifty-pence bargain bins. She couldn’t stand this hobby of mine.

“Look how much space those records take up! If you hadn’t brought those, we could have packed those kitchen rags I got for your mother.”

“In your dreams.”

She shot me dead with her eyes.

“What do you keep buying more for, anyway? Your mother does exact the same thing with those silly little Marujita Collection books. I’ll never understand you two.”

“Just be thankful I didn’t put them in my suitcase.”

from Virtudes (e misterios)/Virtues (and Mysteries), Editorial Galaxia, 2020. Translated and introduced by Jacob Rogers

This is an extended version of a sample translation that appears in The Spanish Riveter

—

Xesús Fraga is a Galician journalist and writer who was born in London and raised between the UK and Galicia. He studied journalism at the University of Salamanca, is a journalist for La Voz de Galicia, and has translated works by Vladimir Nabokov and Julian Barnes among others. He has published a number of books across various genres, and received the 2021 Premio Nacional de Narrativa for Virtudes (e misterios).

Read more (in Galician)

@FragaXesus

Author photo by Sabela Eiriz

Jacob Rogers is a translator from Galician and Spanish. His translation of Manuel Rivas’ The Last Days of Terranova was published by Archipelago Books in autumn 2022, and his translation of Berta Dávila’s The Dear Ones is forthcoming from 3TimesRebel Press.

@bilbyography

The Riveter is a free magazine devoted to riveting European literature in English. The idea is to make international writing popular and accessible to readers everywhere and to celebrate excellent translation and great books from the rest of Europe. The Riveter was launched in 2017 by the European Literature Network. Professionally edited and published by a small dedicated team, it attracts support from a wide range of publishers, authors, translators, critics, academics – and readers. It has achieved acclaim with its special issues on Polish, Russian, Nordic, Baltic, Swiss, Queer, German, Romanian, Dutch, Italian, Austrian and Spanish literature in English. The magazine is distributed free to bookshops, libraries, colleges and other organisations, and at events across the UK and Europe. It is also available to order from newsstand.co.uk (Romanian, Dutch, Italian, Austrian and Spanish) and all editions are free to download digitally from the European Literature Network website. The Spanish Riveter, published in April 2023, is produced by Riveter-in-Chief Rosie Goldsmith, Editor West Camel, Guest Editor Katie Whittemore, Assistant Editor Alice Banks, Design and Production Editor Anna Blasiak, Business Manager Max Easterman and Illustrator Ana Galvañ.

eurolitnetwork.com/the-riveter

@eurolitnet