Négar Djavadi: Neither here nor there

by Mark Reynolds and Farhana Gani

“Magnificent.” Le Soir

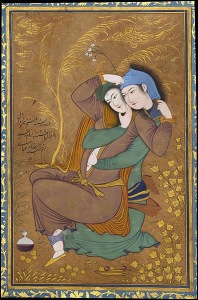

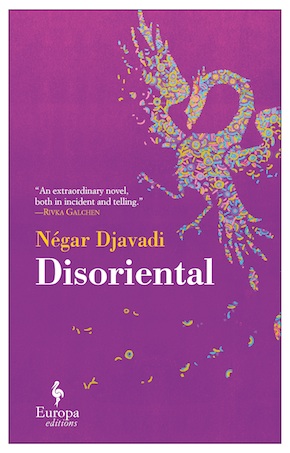

French-Iranian screenwriter Négar Djavadi’s illuminating, richly entertaining debut novel Disoriental combines a sweeping family history in 20th-century Iran with an intimate study of identity and motherhood in contemporary Paris. Kimiâ Sadr is a lesbian punk rocker who spent her teenage years in the French capital after the family fled the trauma of Iran’s 1979 Islamic Revolution. After some wild times in Belgium, Holland, Berlin and London, she has settled down with her lover, and is waiting at the fertility clinic of Paris’s Cochin Hospital to discover whether her IVF treatment has been successful. Her in-the-moment musings at the clinic intermingle with colourful details of her family’s past, going back to the last throes of Persian Empire and feudal courts in the mountains and coastal plains of Mazandaran, through multiple historical struggles and coups d’état – each heavily influenced by outside pressure from Britain, Russia and the US – and the dissident writings and teachings of Kimiâ’s parents Darius and Sara in pre-Revolution Tehran that forced the family’s exile. We caught up with Négar in Paris, right after her trip to launch the book in the US.

MR: The book’s title immediately evokes a sense of separation and uncertainty, and the pressures on an immigrant from the East to shed her past. At what point in the writing did you realise that single, loaded and invented word was a perfect fit?

ND: It’s my word. Before the book I had this word in my head. Because in Paris, and when I was in Belgium at film school, everybody always told me they can’t situate me. When people ask if I’m Oriental or not I always say yes – because I’m Iranian, and Iranians are always polite, we say yes to everybody – but in my head I say to myself, “Tu es désorientale”. What does it mean to be Oriental when you’re not living in the Orient? What does it mean to be Iranian when you’re not living in Iran? When I started to write the book it became the title of a chapter, and the editor told me, “Keep it, but what do you think of it as the title of the book?” For her, it was the perfect title, because Kimiâ is in that same situation.

My father was a journalist; he was fired so many times. My mother was a teacher in the university, one time she talked to her class about Mossadegh and she didn’t work for a year. That was the reality.”

Despite all the tensions in the Iran you grew up in, what freedoms did your family enjoy when you were a child, before exile became the only option?

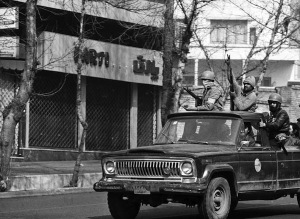

Living in Iran was very cool at that time, on the surface, like in an Agatha Christie book. Iranian people are very cultured. We had everything: theatre, movies, American TV. But that was superficial, and beneath that there was no freedom at all. The jails were full of prisoners. My father was a journalist; he was fired so many times. My mother was a teacher in the university, one time she talked to her class about Mossadegh and she didn’t work for a year. That was the reality. It’s a paradox. If you spoke about the history of Iran, about Mossadegh, everything closed down immediately. SAVAK [the secret police] was everywhere. It’s Mossad who made SAVAK, so it was exactly the same system. One day you have a new neighbour and you immediately think, is he SAVAK? So we were living like that but at the same time everything was very cool – as long as you don’t want to do political things, or think about your country or make things better.

click on images to enlarge and view in slideshow

Was Mazandaran, on the Caspian Sea, a complete escape from Tehran?

Iran is a big country, many times bigger than France. Mazandaran is in the north, about four hours’ drive from Tehran, and it’s like another country. The culture is closer to Georgian, Russian and Armenian than Iranian, so it was very free. They were not Muslim, there was no religion there.

How has that changed today?

I can’t go to Iran, so I can’t talk about Iran now. I have no papers, nothing to prove I was born there. But there is oil in Mazandaran. Afghanistan is to the east, Russia to the north, and a lot of Mazandaran is now pipelines.

It’s very striking to think that the vast majority of today’s population of Iran has only known the Islamic regime. Do you have any regrets at not having been able to return in the last forty years, and perhaps influence how the younger generations view the world around them?

Influence, no. Regret, sure. You always want to see the place you were born, it’s natural, it’s an animal thing, like salmon going back to exactly where they were born to spawn. If you can’t do that, it’s a struggle.

FG: Do you have family there?

Not that much. It’s mostly young people because two new generations now live in Iran. 85% of Iranian people were born after the Revolution. I don’t really have family in Iran. Two cousins, that’s all. I have three children and I want to go there because of my boys, I’d like them to see the country. They speak the language but they don’t know what it means to live there.

Because of the war, because of the regime, girls couldn’t go to school or university, it was very Islamic at the beginning, the repression was so tough. Now it’s not as tough as then. And the young people in Iran today don’t want revolution. They find me on Twitter and tell me, “Our parents made the Revolution and the results were so awful, we want evolution, not revolution. Outside the country you all want the regime to go away, but we don’t want that.”

So what kind of evolution do they want? What could a future Iran look like?

You know, they have the internet, they see all the American TV series. They told me about Breaking Bad and all sorts of shows. They just want to be much more free, because boys and girls can’t walk side by side on the street if they’re not married or engaged. Just to be together, chat together, go to restaurants together, have a girlfriend. You can’t have a girlfriend in Iran. Fiancée, yes, but not a girlfriend. That’s all they want. The authorities often cut the internet, because it’s a way for Iranians to send messages and tell each other there’s an event happening, and the regime’s afraid about that. So not cutting the internet, that’s all: we want the internet, we want to see movies, we want pleasure.

It’s a young population, and very well educated…

Iranian people were always well educated. Here in Paris we have a lot of doctors and philosophers who are Iranian, even if they come from after the Revolution. It’s very like Israel. Iran and Israel and Lebanon all have the same mentality.

There’s a fantastic observation in your book about the difference between Iranian and French culture, where in France the state looks after you, so the French are insular, they’re not very friendly because they’re taken care of. But in Iran they don’t trust the state, so they look to their neighbours and they talk to each other, and the warmth of the Iranians and the coolness of the French are both driven by the state’s manipulation, in a sense.

We don’t need to talk to each other in France. We talk to each other because we are friends and that’s all. We have everything we want, everything is easy so you don’t need other people in your life. In Iran you have nothing, so you need everybody.

In a similar vein, you say that Iranians always tend to fill a silence, whereas Westerners prefer to leave things unsaid. But then in the early pages you have Darius say: “The eyes are better listeners than the ears… If you have something to say, write it.” That seems to speak both to capturing fabulist Eastern tales for posterity, and to a Western sense of applying logic, order and clarity.

Yes, Iranians are always chattering because they have to. Not only in a political sense. Eastern families are very big and there are a lot of stories and it’s the heritage. I remember when I was a child my grandmother always told me and my cousins, “Come here, I’m going to tell you about your great-grandmother.” You are part of a family, and you have to know where you come from. We are part of a small world, the family, and then the wider world.

Darius is a journalist, for him writing means very much, to leave books or articles behind him. If you want to educate people you need books, and that’s why he said that. Chattering is always going to be a part of everything, even politics, but only when you read a book are you alone and you can think clearly.

Kimiâ’s journal in the fertility clinic is typical French literature: it’s my life, and I’m going to tell it. The other side is very cinematographic; it’s Iran, it’s bigger than life, it’s epic, it’s Technicolor.”

The book has a wonderful mix of epic Persian literary flourish and introspective Western autofiction – often on the same page (for example, in Kimiâ’s digressions). Does Kimiâ’s struggle to straddle the two cultures match your own experiences?

Exactly. I wanted this book to reflect both cultures. French culture is very psychological. In contemporary French literature people write their own stories a lot; taking a real story and fictionalising it. You have an experience and you create a story around it. Le nouveau roman, you remember? Nathalie Sarraute, Alain Robbe-Grillet. After the war they said you don’t need fiction; the war was so horrible, so huge, so dramatic, what can fiction do after the World War, after Shoah, after Auschwitz? How can you tell stories after that? You have to think about the world now. And that’s what French writers do, they think about themselves and the world much more than trying to tell a romantic story, a dramatic story. So Kimiâ’s journal in the fertility clinic is typical French literature: it’s my life, and I’m going to tell it. The other side is very cinematographic; it’s Iran, it’s bigger than life, it’s epic, it’s Technicolor.

So how much of the novel is biographical, and how much is fiction? Your bio says that you escaped Iran with your mother and sister by crossing the mountains of Kurdistan on horseback, as Kimiâ does with her family.

The part about the Revolution is not autobiographical, but it’s biography. My father was like Darius, he was a writer who played a big part in the Revolution. He was an intellectual, our apartment was like the Sadrs’ apartment: everyone came to talk with him every day. So that part, the Revolution and the way we left Iran, is similar. But the great-grandfather Montazemolmolk and his fifty-two wives and all the family history is total fiction. I have one sister, I don’t have two sisters; my grandmother is not Armenian, my father is alive and living in the troisième. There are many differences between my life and her life. I only went to Belgium to do my studies, not all over Europe. She lives in Belleville, not me. At film school people told me, “We always read about a child in a war, but never a child in a revolution, you have to tell us about that.” So I always had the idea in my head to write about my life, the revolution, my family, my father, my mother, SAVAK, the house. But I found I needed to create the epic story, and put this experience inside it.

Kimiâ takes the reader by the hand so many times to explain her present situation by taking us back to different moments in the family history. There are so many forks in the story. How did you map it all out?

I wanted to write in the way that memory works. I told myself the structure of the book must be like the structure of memory. When you think about something, when you remember something, it’s never linear, it’s kaleidoscopic. You remember someone and then another story comes, and I tried to do that. When you write a script, you have a lot of characters. You write a scene about a character and you try to finish it with a climax. When you come to this character, you have the climax in your head, and I tried to do that with every part of the past.

Compared with writing a screenplay, how did you approach it?

When you write a script, each character has to have a story begin and end, so I know how to do that. What was not easy was the structure. I’m talking about a country nobody really knows; everyone knows about the Revolution, but not Iran. It’s a big country, it’s a big story, so many coups d’état, so many revolutions, how can I create a shape out of that? And so I told myself the best way is to make a link between a character and an event. Montazemolmolk is the constitutional revolutionary, when Iran had a Majlis, became the first Eastern country with a parliament. The grandmother goes to live in Qazvin, and the coup d’état of Reza Shah was in Qazvin, so I will also talk about the coup d’état. The father leaves Iran and goes to Paris after the overthrow of Mossadegh. Each character is linked to an important event.

Belleville is like punk and rock. Everybody can live in Belleville and nobody will look at you or ask where you come from. Everybody comes from somewhere in Belleville.”

Did you share Kimiâ’s tastes in music and for clubbing as a teenager?

Yes, sure, I really loved rock and roll. Kimiâ, like me, doesn’t really have a country. I’m living in Paris, but if you’re not born here it’s not too easy to be French. You can be Parisian, but not French. The difference between Kimiâ and me is that my country when I was a teen was the cinema. I told myself, “You’re not Iranian, you’re not French, so you have to go somewhere, choose something, make something.” And I chose cinema, the world of fiction. For Kimiâ it’s the music, because when she’s a teen she finds rock and roll and punk, and all those guys are like her.

Why is Belleville is the perfect place for Kimiâ to wind up?

Belleville is like punk and rock. Everybody can live in Belleville and nobody will look at you or ask where you come from. Everybody comes from somewhere in Belleville. The first immigrants in Belleville were Corsican, a lot of Jewish came after the Second World War from Poland and elsewhere after the Pogroms, and after that came Jews from North Africa, Tunisia, and after that there were Chinese, so all kinds of people live in Belleville. Lots of artists too, because it’s not very expensive there.

Are there any prejudices or resentments among the various immigrant communities?

In Belleville yes, but not in Paris. The French Republic is one and unique: La République est une. You have to be French, you have to integrate very quickly, but in Belleville it’s different. You can be who you are, and sometimes there is tension.

You paint a disturbing picture of Iranian government agents assassinating dissidents on the streets of Paris. Was your father under the same kind of direct threat when he was first exiled here?

My father wasn’t assassinated, but he was on a list of targets. In the 1990s, after Shapour Bakhtiar was murdered outside Paris, the French government arrested two terrorists who came from Iran aiming to kill other opponents of the regime, including my father. The French government asked him to come to the Ministry of the Interior and they told him, “You are on the list.”

Was his reaction to that the same as Darius, to just carry on regardless?

Yes. Did you know that Bakhtiar’s son was the chief of the police here in Paris? Bakhtiar’s wife was French, so Guy Bakhtiar was half-French, half-Iranian and he became chief of the police department. It’s amazing, Guy Bakhtiar was responsible for protecting his father, and yet they assassinated him in his own house. If it can happen to Bakhtiar there’s nothing you can do.

Glancing inside the French edition, the English seems to be a very direct translation.

It’s an amazing translation. Word by word, Tina Kover did such a good job.

Did you work closely with her on the translation?

No, not at all. She never called me to ask me how to translate this or that. The Italian and German translators did, but not Tina. She sent me tweets about some of the dishes though, saying she’d tried this and that and they were very flavourful!

Do you have a sense of how widely the French edition has been read in Iran?

I know the book is in Iran, because a few journalists who are part-Iranian, part-French are working there. I saw one of them here a few months ago. She lives in Paris but spent time in Iran, and she told me she took the book with her and gave it to another journalist who is living in Iran. I know the book is in Iran, but that’s all. There’s no Persian translation that I know of, but Iranians do what they want with books, there’s no copyright law so you don’t have to pay the writer if you translate a book. They translate all kinds of books, but they don’t contact the writer.

What kind of audiences came along your events in the US? Were there a lot of Iranian expats?

Not so much, no. In Albertine, the French bookshop in New York, it was French people. I only saw two or three Iranians. There were a lot of Americans and French and others. I did readings and talks with authors from India, Pakistan, Africa, South America and Eastern Europe, so there was a whole variety.

Are you planning any more fiction, or is the screenwriting keeping you too busy?

Screenwriting is keeping me busy. I have to finish a lot of things I wasn’t able to finish because of the book, but I’ve started to write something, yes.

When I read Salman Rushdie I told myself, no need for a door, you are who you are, it’s your country, you live here and you can talk about it. That was very important for me.”

Who do you count as your main literary influences?

Not so much for this book, but Salman Rushdie is a big influence for me, for what he says in Imaginary Homelands, his anthology of essays. He talks to Indian writers in Britain and says, you have to write about England, that’s your country. Take the language and make what you want of it. When I read that, I told myself yes, that’s the way I have to think, because French literature is very important – Balzac, Zola – it’s so rarefied, how can I go in? How can I even find the door? And when I read Salman Rushdie I told myself, no need for a door, you are who you are, it’s your country, you live here and you can talk about it. That was very important for me. The author I most admire is Virginia Woolf, because she’s so free. Each book is different, a different structure. The Waves is amazing, Orlando is completely different. With each book she takes a risk.

Finally, Donald Trump is again threatening to sabotage the 2015 nuclear deal with Iran. How do you view the prospects for the country and the wider Middle East during – and after –Trump’s presidency?

I think Iran is a target for America. Nowadays it’s Trump, but also going back to the Bush administration. If you look at the map, all the surrounding countries are in America’s hands: Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Dubai, Afghanistan, Iraq, and I think Iran is a target because of petrol, gas, so many things. Russia is to the north, and it seems we’re at the start of another Cold War. Putin is on that path, and Iran is again caught between East and West. It was always like that, that is the story of Iran, it’s the country in between. Everything that’s emanating from Middle East – terrorism, DAISH, the Twin Towers, Bataclan – it all comes down to the war between Sunnis and Shi’ites, and Iran is the country of Shi’ites. It’s a long, long story. I don’t think the American administration realise what it means for Iranians to be Shi’ite. The Iranian people hate everything Sunni. They killed Ali, they killed Husayn, they killed all the saints. Sunni are the enemy, it runs so deep. It’s my feeling that Western administrations don’t understand Eastern people and countries, all the ancestral conflicts. And how can they come and govern and disturb and bring down all these countries when they don’t understand them? That’s my fear. And Trump much more than Bush. Bush was horrible, but Trump is twice as bad.

Négar Djavadi was born in Iran in 1969 to a family of intellectuals opposed to the regimes of both the Shah, then Khomeini. She arrived in France at the age of eleven, having crossed the mountains of Kurdistan on horseback with her mother and sister. She is a screenwriter and lives in Paris. Désorientale (Editions Liana Levi, 2016) scooped six awards including the Prix Roman-News, Prix du Style, Lire Best Debut Novel and the Prix littéraire de la Porte Dorée. It is now published as Disoriental by Europa Editions in paperback and eBook, translated by Tina Kover.

Négar Djavadi was born in Iran in 1969 to a family of intellectuals opposed to the regimes of both the Shah, then Khomeini. She arrived in France at the age of eleven, having crossed the mountains of Kurdistan on horseback with her mother and sister. She is a screenwriter and lives in Paris. Désorientale (Editions Liana Levi, 2016) scooped six awards including the Prix Roman-News, Prix du Style, Lire Best Debut Novel and the Prix littéraire de la Porte Dorée. It is now published as Disoriental by Europa Editions in paperback and eBook, translated by Tina Kover.

Read more

@NegarDjav

Author portrait © Philippe Matsas / Opale / Leemage / Editions Liana Levi

Tina Kover’s translations include the Modern Library edition of Georges by Alexandre Dumas, The Black City by George Sand, and Anna Gavalda’s Life, Only Better. In 2009 she received a National Endowment for the Arts Literature Fellowship for her translation of Manette Salomon by Edmond and Jules de Goncourt.

@tinakover

Mark Reynolds and Farhana Gani are founder editors of Bookanista.

@bookanista