Nicci French: What lies beneath

by Farhana Gani

“Clever, compelling, original and twisty.” Erin Kelly

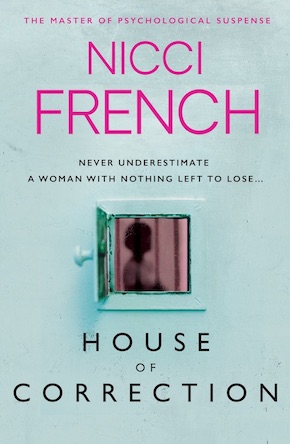

The novel begins with a scream. It’s 3am and Tabitha has been woken up by the human howl. She’s in prison.

Tabitha is currently on remand at Crow Grange Prison. She’s accused of murdering her neighbour and former maths teacher Stuart Robert Rees, whose body was found in her garden shed. She was found covered in the victim’s blood, and CCTV footage shows that she was the only person on the premises at the time of his death. She knows she didn’t kill him but her memory of the day is fuzzy, and her erratic behaviour at the police station has persuaded the officer in charge that she’s the only suspect.

What can she do? Her own court-appointed lawyer steers her towards pleading guilty to a lesser charge of manslaughter by diminished responsibility for a reduced prison sentence. The police investigation reveals she had a motive, making the prosecution’s case against her even stronger. But Tabitha is adamant. She didn’t commit the murder.

After her mother died, Tabitha returned to live in Okeham, the small village she grew up in, buying the house next door to the Rees family. She barely knows anyone there, but amongst themselves the locals quickly formed their opinion of her and it was not pretty. She was a loner, agitated, unfriendly, depressed, aggressive. She dressed like a man, swam in the cold sea every morning, and she refused to buy a poppy on Remembrance Day, which further raised eyebrows.

Stuck in prison waiting for her hearing, and dependent on what little information her lawyer provides, Tabitha is bereft, confused and untrusting. Only when she decides to argue her defence herself does Tabitha begin to feel in control of her own destiny. As she scrutinises the case against her, she begins to form a clearer picture of the village and its inhabitants. Stuart Rees might have been a longstanding and established member of the community, but he was a well-disliked man. “Nobody went to his funeral who didn’t have to go.” Villagers may not have mourned him, but did any of them have a clear enough motive to actually kill him?

House of Correction is the latest thriller from Nicci Gerrard and Sean French, the husband-and-wife writing team who publish as Nicci French. Last year’s The Lying Room was a riveting tale of Neve, a married woman trying to remove every trace of the double life she led after finding her lover’s dead body in his flat. House of Correction also focuses on a woman fighting for her freedom, but that’s where the similarity ends. While Neve’s action takes place out in the wider world – her home, her workplace, among her friends and family, Tabitha’s fight is confined within correctional facilities – either the prison or the courtroom.

In this claustrophobic world Tabitha is interrogated and dissected. Prison staff humiliate her. Psychologists assess her. Witnesses disparage her. She may appear lonely, vulnerable, confused and shattered but that is not how she sees herself. As a freelance copyeditor for a scientific publisher, she’s all about fact-checking, precision and accuracy, and she’s about to put these finely-tuned skills to the test. She’s unwilling to give up on the certainty nagging away in her head that she is innocent. The only way she can avoid a murder conviction is to persuade the jury that there is reasonable doubt about the charge against her. Tabitha is not an endearing woman, and it’s pleasing to warm to a difficult character as her personality unfolds. In spite of her fits and rages she deserves a fair trial. Will that be enough to clear her name?

Describing it as a suspenseful prison thriller, or riveting courtroom drama doesn’t do this meticulously written detective novel justice. There is detail to sift through, CCTV footage to analyse, behaviour of the villagers to decipher. We become Tabitha’s shadow as the events surrounding that fateful day become clearer and more revealing. As well as its finely drawn characters and clever storyline, this is a novel that provokes you into pondering the workings of the wider justice system, police methods and prison life.

In these two post-Frieda books we’ve written about two women who are different from each other but they’re more ordinary, more like us. But it wasn’t a plan. These are just the stories we stumbled into.”

“Expertly paced, psychologically sharp, thoroughly enjoyable.” Louise Candlish

FG: House of Correction and your previous novel, The Lying Room are two standalone novels. Both are clever, page-turning thrillers and both feature determined women who go about saving themselves in very different ways. Are these two novels signaling a new direction for you?

NF: We spent almost ten years writing the Frieda Klein series. One of the characteristics of Frieda is that she’s a dominant character – an alpha female, you might say – and in these two post-Frieda books we’ve written about two women who are different from each other but they’re more ordinary, more like us. They don’t feel specially equipped to deal with the terrible events they face. But it wasn’t a plan. These are just the stories we stumbled into.

Tabitha is a volatile yet sympathetic character. If the book were adapted for film or TV, who would you like to see play her?

She’s small, she’s vulnerable, she’s fierce, she’s an outsider, she starts at rock bottom and somehow manages to save herself. Florence Pugh would be terrific (she’s been terrific in everything else she’s played).

The book is primarily set in two places – a prison and a courtroom. How did this structure for the novel take shape?

Our very first idea was to set the story entirely in a prison. We were intrigued by a detective solving a crime entirely in her head, without being able to go anywhere, visit the crime scene, interview witnesses. But we quickly realised it would be much more dramatic if she could confront her accusers and enemies face to face, a firecracker in a closed space, wildly and unruly in a place so bounded by rules and respect for authority. And if she defended herself in court, she could ask them questions and they would have to answer.

Tabitha observes that the prisons felt so prison-like: “The doors really were made of heavy metal. They really did clang shut. The warders really did carry huge bunches of keys attached to chains on their belts.” Can you tell us about the research you undertook to create an authentic prison experience?

We’ve been to prisons numerous times, talking to reader’s groups, meeting inmates. It’s been fascinating and rewarding for us, but it’s also deeply disturbing. Those experiences of shutting doors and the keys were absolutely ours. We felt genuine claustrophobia as we went further in, through door after locked door – and we were allowed to leave at the end of the day. We visited cells that felt too small for one person that were occupied by two people. And at times of crisis they might be kept there for 23 hours a day, or even 24. Prison conditions in Britain are a national scandal.

Mary Cole, the prison governor, is a tough no-nonsense woman. Why is it necessary for prison heads to be so overtly formidable, brutal and uncompromising?

We can’t speak about specific examples. All we’ll say is that prison staff get institutionalised in their own way. UK prisons are under-resourced, understaffed and appallingly overcrowded. That will tend to dictate a particular kind of management style. And of course, it was necessary in this particular book: Tabitha has to feel utterly alone.

There is an old legal maxim that a person who defends themself has a fool for a client.”

Rule Number One of prison life is “never ask anyone what they’re in for.” Why is this? Surely that’s the first thing you’d want to know about your fellow prisoners?

Everyone understands that the details of your crime might make you a target from some other inmate – and this doesn’t only apply to sexual offences. So it’s a crucial part of the culture to be discreet and not to be too curious.

Tabitha sacks her lawyer and elects to run her own defence. To take on the criminal justice system like that is an incredibly brave – many said daft – thing to do. Was there an inspiration for her character and her decision? How common is it for criminal trials to be defended by the accused?

We almost felt like appending an author’s warning note at the end of the novel: Don’t even think of trying this yourself. There is an old legal maxim that a person who defends themself has a fool for a client. There is a tradition in certain very politicised trials of people defending themselves to make a particular point. The most famous recent example was the ‘McLibel’ case, in which McDonald’s sued two environmental activists for libel. The resulting trial lasted for ten years and was a catastrophic own goal for McDonalds. But what has become dismayingly common in recent years is people defending themselves because they can’t get legal aid and can’t afford a lawyer. This is about as sensible – and as likely to succeed – as operating on yourself because you can’t afford a doctor. Tabitha does it in despair and in stubbornness and in recklessness.

It’s also alarming to consider how many falsely accused take the plea-bargaining option when faced with the prosecution’s case. Do you think the numbers should trouble us as a civilised society?

It is reasonable that people should get a reduced sentence for pleading guilty and limiting the general agony and expense for everyone concerned in a trial. But it is scandalous when prosecutors tempt innocent people to plead guilty to avoid the risk of an absurdly long sentence. But there are so many problems with the current legal system: accused people awaiting trial for years, the lack of access to legal aid, acquitted people still facing ruinous legal bills. The incompetence of magistrates’ courts is notorious.

Tabitha’s cellmate Michaela is a compelling character. Even though she hardly says anything, her presence is strong. Was that always your intention or did she emerge in that way as you were writing?

It was important that the other prison inmates weren’t just vaguely hopeless or malevolent figures in the background. We wanted to show another inmate who had agency, who could develop. Also, Tabitha was so horribly alone. We needed to give her someone to help her! And then, in the writing, Michaela became increasingly important – to Tabitha, and to us.

The police officers in charge of the investigation are biased from the start. Such institutional bias has been highlighted in recent news, particularly in the US with the #BLM protests around police brutality. How do you think the UK police compare?

Many police forces in the US are utterly out of control – under no proper authority. On the whole the UK police compare favourably to that. But there is an institutional problem that is as much about cognitive bias as political bias. Police often begin an investigation ‘knowing’ who did it and finding the evidence to prove it. If they are wrong, it’s hard to alter that mindset. It’s a very human way of behaving but the results can be catastrophic.

Did you base the prosecution lawyers and judge on anyone in particular? How did you shape them?

We spent days observing trials and tried to convey the personalities we saw in basically accurate – but also entertaining – ways. With all the reforms that have taken place, a crown court trial still feels very white and very posh. However, we thought it would be interesting to make some of the main authority figures – the prison governor, Tabitha’s lawyer, the judge – female.

You famously go away every year to work on ideas for your next novel. How did lockdown affect your writing process this year?

Our writing process was about the only thing unaffected by lockdown. We went walking in September 2019 and by the time the national lockdown happened we were already in lockdown, deep in a novel. In fact, our lockdown life was more sociable than usual. There were nine of us (and three cats), finding a corner somewhere to work in. It was fun, emotional, collaborative, a bit messy, very vivid and intense

And did it affect your reading matter?

Reading is always at the heart of our life alongside writing. They go hand in hand. But normally we spend a lot of time going to exhibitions and concerts and plays as well. There was none of that in the first half of the year so we read more and watched more movies and TV than usual.

Will the pandemic feature in your next novel?

We made a solemn vow early on not to write a thriller about a group of people who find themselves in lockdown. Publishers and agents and filmmakers must be dreading the flood of thrillers, dramas, sitcoms, plays and romcoms about people in lockdown that will be coming their way in the next year or so. Speaking for ourselves, it’s the last thing we want to see or read about. And actually, this novel is (inadvertently) our lockdown novel.

When we started writing together, we just cobbled together a method that worked for us. We do the research and planning together. We talk about story and character. But we always write separately.”

Crime has so many definitions. There’s murder and then there’s corporate crime. The pandemic has even led to the suggestion that government negligence led to lives being lost. Is that also a crime? Are our justice systems properly structured to deal with crime at all levels?

That’s a very deep and complicated issue that is probably too deep and complicated for two crime writers to answer! Governments are constantly making decisions that result in people dying – declaring war, allocating resources in medical treatment in one way or another. Generally the way to deal with a negligent government is to vote them out of office. On the other hand, when the government behaves illegally or corruptly, you need some mechanism to deal with it. We seem here (and even more in the US) to be drifting towards the Richard Nixon ‘defence’: if the president does it, it can’t be illegal.

Are there any public figures you’d like to hold to account for ‘criminal’ behaviour?

What we would like, boringly, is for there to be strong independent institutions, the legal system, the civil service, the BBC. Sadly, an elected government has a right to do things that annoy people like us, but it shouldn’t have the right to be corrupt or to break its own laws.

How do the two of you work together and how do you resolve any conflicts that might arise in the writing process?

Finally, an easier question! When we started writing together, we just cobbled together a method that worked for us. We do the research and planning together. We talk about story and character. But we always write separately. One of us will write a section, then send it to the other, who is free to edit, rewrite, adjust, cut entirely or do nothing at all. Then they carry on and we pass it back and forward, constantly discussing and arguing and writing until we have a first draft. In the rest of our marriage we resolve conflicts by arguing and sulking and somehow getting through. With our books, we just talk and talk but in the end it depends on trust. We each have to believe that it’s not a fight for control, for one person’s vision. It’s all about the book, what this story needs. If we didn’t have that trust, then we would have ground to an acrimonious halt in the first few chapters of our first book.

How much does true crime inspire or influence your fiction?

How much does true crime inspire or influence your fiction?

Not very much. Our ideas tend to come much more out of ordinary life. The Lying Room really started from our feelings about the secrets there are even in a long, apparently secure marriage. With House of Correction, we were fascinated by how you can look back at things that happened when you were young and realise that they weren’t how they seemed at the time. If it is to be used in fiction, ‘true crime’ needs to be reworked into a narrative shape that life simply doesn’t have. We now know that the supposedly ‘true crime novel’ In Cold Blood was crammed with Truman Capote’s fabrications and pure inventions. It had to be.

Crime novels and TV crime dramas continue to be one of the most popular genres with audiences. What is the enduring appeal of crime stories?

It’s a fascinating question that speaks to something deep in human psychology. Why is it that small children like stories about ghosts and witches and dark forests? There is surely something therapeutic – and also enjoyable – about facing our fears in safety. But more than that, the crime novel seems like a wonderful form for exploring our anxieties, for what lies beneath, for the things we don’t talk about. We live our lives on thin ice. We’re always just a step away from things going terribly wrong. Crime fiction is a way of facing up to that.

How do you relax between novels, and what have been your cultural highlights so far this year?

There is no ‘between novels’ for us. When we’re not writing, we’re talking about writing. But we absorb a lot of culture. We run and walk and cycle and Nicci swims in any accessible body of water. We cook and eat and drink. As we’ve said, our cultural highlights were necessarily a little different this year. We’ll answer this particular question separately:

Sean: Books I’ve particularly loved this year are True Grit by Charles Portis (much better than either of the movie versions), Lucky Per by Henrik Pontoppidan (a genuinely great Danish novel, published in 1904 but only translated into English in 2010), Dirty Snow by Georges Simenon and various wonderful novels and stories by Sylvia Townsend Warner. Like everyone else we were pleasurably stunned by the TV series I May Destroy You and we finally discovered and loved Schitt’s Creek after years of being put off by the title. As for movies, if you fancy a Soviet version of Brief Encounter, try the recently re-issued 1959 movie, The Cranes are Flying. Beautiful and moving.

Nicci: We spent much of lockdown watching Ingmar Bergman’s films (including Winter Light, Wild Strawberries, Seventh Seal, Persona, Fanny and Alexander and his harrowing TV series and portrait of a marriage in meltdown, Scenes from a Marriage). I loved Hilary Mantel’s final Wolf Hall novel, and Maggie O’Farrell’s Hamnet, and Jenny Offill’s Weather. I loved turning off the news and waking up to Radio 3 and music. I loved Jonathan Glazer’s blistering and euphoric short film for television, Strasbourg 1518, in which people dance with increasing frenzy in empty rooms. Oh, and I mustn’t forget the real live events we went to before lockdown started, which seems a world away: the Eliot Prize readings, where the ten shortlisted poets read from their works to a large audience; David Copperfield at an actual cinema; a fabulous production of Uncle Vanya; and the folk singer Martin Simpson at Kings Place in north London on March 14: the last time we went to a concert, or to any public event.

Nicci French is the pseudonym for the writing partnership of journalists Nicci Gerrard and Sean French. The couple are married and live in London and Suffolk. House of Correction is published in hardback and eBook by Simon & Schuster. The Lying Room is now in paperback.

Nicci French is the pseudonym for the writing partnership of journalists Nicci Gerrard and Sean French. The couple are married and live in London and Suffolk. House of Correction is published in hardback and eBook by Simon & Schuster. The Lying Room is now in paperback.

Read more

@NicciFrenchOfficialPage

@FrenchNicci

Author portrait © Jonny Ring

Farhana Gani is a freelance writer and a founding editor of Bookanista.

@farhanagani11

@bookanista

wearebookanista