A night in the barn

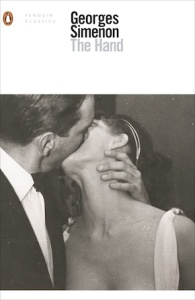

by Georges Simenon The Red Barn at the National Theatre” width=”400″ height=”267″>David Hare’s The Red Barn, his latest sell-out play at the National Theatre, is a bold adaptation of Maigret creator Georges Simenon’s hitherto obscure novel Le Main, which is also now released by Penguin Classics in a new translation.

The Red Barn at the National Theatre” width=”400″ height=”267″>David Hare’s The Red Barn, his latest sell-out play at the National Theatre, is a bold adaptation of Maigret creator Georges Simenon’s hitherto obscure novel Le Main, which is also now released by Penguin Classics in a new translation.

In the depth of winter in 1950s Connecticut, Donald and Ingrid Dodd (Isabel in the novel) make their way from a society party through a blinding blizzard with their guests Ray and Mona Sanders. Abandoning the car a short distance from home, trudging through drifting snow with only a fading torch to guide them, the women make it inside, followed by Donald, but Ray has somehow slipped from his friend’s grip.

The novel is narrated by a tortured Donald, who probes his conscience for a possible motive to have deliberately left Ray behind. For the play, Hare fleshes out other characters to bring Donald’s desperation and doubts into full view. Mark Strong puts in a shattering shift as Donald, looking back on a lifetime of mediocrity, misplaced loyalty and unspent passions. Hope Davis’s Ingrid is uncannily, almost imperceptibly manipulative, and Elizabeth Debicky’s Mona unsettles as an icy temptress.

But the biggest star is the set. Hare peppers the playscript with almost impossibly contrasting situations, piling 24 scenes across the continuous two-hour piece. Director Robert Icke and designer Bunny Christie meet the challenge with an ingenious mechanised screen that shrinks and widens like an aperture, focusing on a tiny detail before revealing often disorientating transitions, dragging the eye to a corner of the stage as the next scene lurks elsewhere.

This extract from the early pages of the novel describes the beginning of Donald’s all-consuming angst – and amplifies the task Hare set himself to externalise the action.

I will say everything, obviously, otherwise it would not have been worthwhile to begin. And, first of all: at no moment of the evening was I completely drunk.

If I try to define my state as accurately as possible, I’d say that I possessed a warped lucidity. Reality existed around me, and I was in contact with it. I was aware of my actions. Taking pencil and paper, I could record almost exactly the words I spoke at the Ashbridge party, in the car afterwards and, later, at home.

Suffering from the cold on my bench, however, where I lit one cigarette after another, I was entering, I felt, a new lucidity, which made me uneasy and was beginning to frighten me.

I could sum it up in a word – in four words, rather, which I seemed to hear out loud: “You have killed him…”

Perhaps not in the legal sense. But then again, isn’t the refusal to help someone in danger considered a kind of crime?

When I had left the house, when the two women had sent me out to look for Ray, I had gone immediately to the right. More precisely, to fool them, in case they’d been watching me from the window and seen the glint from my flashlight, I’d first walked straight ahead for a few yards and then, safe in the darkness, I had veered right, knowing that I would find the barn about thirty yards along.

I was physically exhausted and think I can say that my morale was spent as well. This enormous storm, this world gone mad that had earlier elated me to the brink of nervous hilarity, now suddenly scared me.

It would have been a miracle if he had heard me, just as it would have been if he had glimpsed the glow, way too weak, of the flashlight through the snow falling almost parallel to the ground.”

Why had the women stayed in the house? Why hadn’t they, too, come along to search? I thought back to Isabel, impassive, looking like a statue with her silver candelabra held a little higher than her shoulder. Mona, her features blurred in the shadowy light, had said nothing.

Neither of them had seemed to understand that a real tragedy was taking place and that by sending me outside they were putting me, too, in danger. My heart was beating too fast, in fits and starts. At every moment I kept losing my breath.

I was afraid, I’ve already said so. I called out one or two times more.

“Ray!…”

It would have been a miracle if he had heard me, just as it would have been if he had glimpsed the glow, way too weak, of the flashlight through the snow falling almost parallel to the ground. It wasn’t falling, it was whipping, thrown forward in actual clumps that hit you in the face and smothered you.

I heard the barn door creak and rushed inside, where I collapsed on the bench.

A red bench. A garden bench. I did see the grotesque aspect of the situation: in the middle of the night, in the middle of a blizzard, a forty-five-year-old man, a lawyer and respectable citizen, sitting on a red bench lighting a first cigarette with a trembling hand as if this were going to warm him up.

“I killed him…”

Perhaps not yet. Doubtless he was still alive, but dying, in danger of death. He was not familiar, as I was, with the area around the house and if he veered to the right, if he was off by just a few yards, he would tumble down a small cliff into a freezing stream.

That was nothing to me. I did not have the courage to look for him, to run the slightest risk. On the contrary.

And here is where I’ve arrived, where I am indeed forced to end up. Here is where I was heading little by little, on that particular night, the night of 15–16 January, on my bench, in the barn: what was happening to Ray did not displease me.

Extracted from The Hand, translated by Linda Coverdale and published by Penguin Classics

Georges Simenon was born in Liège, Belgium in 1903 and died in 1989 in Lausanne, Switzerland, where he had lived with his family for the latter part of his life. Best known for his Maigret novels and stories, he was also a prolific writer of romans durs. Written in 1968, The Hand takes its setting from the years Simenon spent living at Shadow Rock Farm in Lakeville, Connecticut in the early 1950s.

Georges Simenon was born in Liège, Belgium in 1903 and died in 1989 in Lausanne, Switzerland, where he had lived with his family for the latter part of his life. Best known for his Maigret novels and stories, he was also a prolific writer of romans durs. Written in 1968, The Hand takes its setting from the years Simenon spent living at Shadow Rock Farm in Lakeville, Connecticut in the early 1950s.

Read more.

Author portrait © Jac. de Nijs/Anefo/Dutch National Archive

Linda Coverdale has a Ph.D. in French Studies and has translated more than sixty-five books, including works by Roland Barthes, Marguerite Duras, Tahar Ben Jelloun and Jean-Philippe Toussaint. A Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres, she has won the 2004 International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award, the 2006 Scott Moncrieff Prize and the 1997 and 2008 French-American Foundation Translation Prize. She lives in Brooklyn.

The Red Barn, National Theatre” width=”371″ height=”250″>The Red Barn ran at the National Theatre from 6 October 2016 to 17 January 2017.

The Red Barn, National Theatre” width=”371″ height=”250″>The Red Barn ran at the National Theatre from 6 October 2016 to 17 January 2017.

More info.