Nome’s Lemming Lady

by Michael Engelhard

CHANCING UPON THE WORK of an obscure writer in your genre or field – one before overlooked – triggers joy with a twinge of embarrassment. After all, most authors are proud to know literary predecessors and ‘the competition’. The surprise discovery feels a bit like snatching an Easter egg while competing in the hunt with amped-up four-year-olds.

One such find for me has been the nature writer Sally Carrighar, an undeservedly lesser-known Rachel Carson. Her contemporaries, who also included Aldo Leopold, overshadowed Carrighar for her apolitical stance, not for the quality of her writing. She entered my purview during research for my latest book, No Place Like Nome. I most admire her for the degree to which she immersed herself in other-than-human worlds, her ability to switch perspectives, to turn a damselfly’s existence into drama. She lets us experience animal realities through animal senses, which often surpass our own.

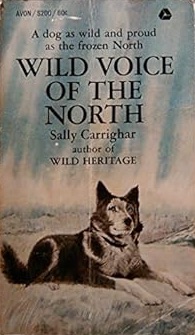

Rodents nesting inside one’s home would prompt most people to set traps or to call pest control. For this Midwestern naturalist, during one season in Nome, they presented a chance to hone her literary and observational skills. Lemmings teem on the pages of her Icebound Summer, rubbing shoulders with walruses, arctic foxes, and whales. She wove them into the narrative as a theme, partly because she saw their short lives as symbolic of that season’s brevity in the North. They also pop up in Wild Voice of the North, her 1959 memoir of living with Bobo the ‘boss dog’, a blue-eyed gift, part wolf, part Siberian husky.

Bobo became a celebrity through a 1953 portrait in the Saturday Evening Post Magazine penned by his new owner, who once ate hamburger while she fed him prime moose steak. His rise to the top of Nome’s fierce canine society held echoes of Buck in Jack London’s Call of the Wild. Unlike Buck, who in print forever “sings a song of the younger world, which is the song of the pack,” Bobo declined in his twilight years; but even then, Carrighar writes, “enfeebling age could not rob him of his dignity and sense of authority.”

Her lemming descriptions glow with intimacy, the knowledge that rubs off between housemates.”

Carrighar evoked faunal characters in the way of a page-turner, melding scientific scrutiny – insights gleaned through the then still young discipline of ethology – with empathy. She was, in the words of one critic, an “animal anthropologist”: a “visitor seeking admittance into the animals’ community.” Her lemming descriptions glow with intimacy, the knowledge that rubs off between housemates. Often, “they would stop in a kind of rapt pause, with their heads tilted pertly as if they were weighing delicious choices.” They slept “curled over like infant porcupines, with their fur pushed out and their small button noses cushioned upon their chests.”

In 1950, in Unalakleet, she had searched in vain for the prolific critters. Her butterfly net at the dug-up burrows stayed empty. Not even the local Inupiaq Eskimo kids, “whose interest in everything about animals is always intense and spontaneous,” found any for her. The Coast Guard ferried Carrighar to St. Lawrence Island, but none could be captured there either, as if they had dissolved into thin air. Upon landing, she was told that the hordes reported were “mice” – tundra voles, in fact. Her Norton Sound stay, she had realized, coincided with one of the famed lemming population crashes that happen about every thirty years.

A myth persists, perpetuated by the 1958 award-winning classic Disney documentary White Wilderness, that lemmings periodically commit mass suicide in the open sea. In fact, lemmings, which can reproduce when they’re a month old, migrate in waves to forage at the peak of population spurts. Carrighar, in her biocentric, species-subjective, mind-in-a-foreign-body style, rendered that frenzy thus: “There were too many lemmings – that was the core of their difficulty… Being sensitive little beasts, they became overstimulated by superfluous numbers of their own kind. They had tried to escape, but with pitiable irony, all tried to escape together.” In addition, she would learn that lemmings swim rather well. They waxed frantic near the time of each full moon, and Carrighar put them in a tub partly filled with water to calm them. She thought lunar phases might explain their urges to migrate.

She’d finally managed to study her subjects up close and personal, though in much smaller numbers, after obtaining five specimens from children in Barrow, where she flew in on a charter plane that afterward wrecked, stranding her in town. One of the “tiny marmots” that she guarded against Bobo later birthed two litters. A sixth had been turned loose, as it was so combative it endangered the others. She reasoned that relocating lemmings from Alaska – “away from their own kinds of food, water, hours of daylight, barometric pressure, weather, relation to the Magnetic Pole” – would imperil them or skew her results. Perhaps she quailed at yanking them from their environment, recalling her own birth by forceps, which had disfigured and traumatized her: she had suffered nerve damage and underwent reconstructive jaw surgery. Her mother, a psychotic, abused her verbally, urged her to commit suicide and once tried to strangle her. During a phase of depression and heart disease, Carrighar had begun to communicate with birds she fed on her windowsill, and a mouse that lived in her radio sang to her. Still, she dodged anthropocentrism, a narrowing perspective, in her writing. Soured on humanity, she never had children or married.

When Carrighar moved in, an eight-foot bathtub sat in the middle of the bedroom, which was strange, since there was no second-floor plumbing.”

Carrighar’s Nome research base and ersatz colony was a late Victorian mansion she bought, the only house in town that had wallpaper and probably the first two-story house on the Bering Sea coast. A square tower with a pyramid roof sprouted at its front, and it was clad with clapboards on the first story and wood shingles on the second. Special arrangements had been made, because permafrost otherwise warped all the walls. A Jewish miner had built it in 1903-04, a native of Germany, “a generous, whole-souled man” made flush by three major strikes during the gold rush.

Unusual for the period in its size and number of windows, the Jacob Berger house (now on the National Register of Historic Places) looks like a rustic cross between the Home Alone home and a Transylvanian castle. When Carrighar moved in, an eight-foot bathtub sat in the middle of the bedroom, which was strange, since there was no second-floor plumbing. Hot water had to be carried one teakettle at a time. Wind entered not only through cracks in the walls but through the downstairs plumbing as well. At times, the draft was strong enough to lift her hair while she stood in the living room. Other sources relay that elsewhere on this coast, because of the powerful winds, “front doors had to be fastened permanently and an entrance made at the back.”

The lemmings occupied habitats Carrighar had commissioned. One group was downstairs. The other, in a sort of free-range replica upstairs, was meant for restocking her first-floor population if necessary. She gained a reputation among some Nomeites of raising rats and letting them scurry all over her house.

Her subjects stayed busy, despite their new surroundings. She quickly noticed play involving a metered activity wheel – think hamster cage gym-cum-Fitbit – and she thought that her “little zoo functioned to everyone’s satisfaction.” Nests she repositioned were reassembled by the following morning in their old place. The lemmings had “more fire, more drive” than mice, and more impatience.

As in the baffling cyclical lemming die-offs northerners observe, after several months her wards started to disappear from the glass-sided vivarium like Bering Strait sea ice in June. One under her care had fallen into the drip tray beneath the oil heater and died days later, despite her giving it a soapy bath (an example for why oil extraction in the Arctic is never a good idea). Another she found with its throat torn, a wound inflicted in fighting. Always, she heard them topside, “running about, spinning their wheel, chirring.” And then, “from a certain day on,” there was silence. With the help of an Inupiaq youth, Carrighar dismantled that room, sifting through the soil, barrels of grass, and driftwood she stored there to replenish her indoor tundra facsimile. But the fate of the final four, like that of twenty-four people allegedly gone missing from Nome between 1960 and 2002, remains a mystery. The FBI, investigating the human disappearances, concluded that Alaska’s harsh wildness was likely to blame. Still, as in the case of the vanished lemmings, foul play cannot be ruled out.

Adapted from No Place Like Nome: The Bering Strait Seen Through Its Most Storied City.

—

Michael Engelhard trained as an anthropologist with a degree from the University of Alaska Fairbanks, and worked for twenty-five years as a wilderness guide and outdoor instructor in Alaska and on the Colorado Plateau. His books include Ice Bear, a cultural history of the polar bear; the National Outdoor Book Award-winning memoir Arctic Traverse; and What the River Knows: Essays from the Heart of Alaska. His writing has also appeared in Outside, Sierra, Backpacker, National Parks, Audubon, Utne Reader, the Times Literary Supplement and Alaska magazine. No Place Like Nome is published by Corax Books.

Bookshop.org USA

Amazon UK

michaelengelhard.com

Also by Michael Engelhard on Bookanista:

That sinking-feeling

(extract from Ice Bear)