Oceans of stories

by Lisa Blower

“These are short stories to die for.” Kit de Waal

258 people used to live in this road and I knew everyone’s names. I’d lie in bed, young back then, and count. Numbers 1 to 60 Ocean Road. The ten Arkwrights to Winifred Waters. 258 people, 258 names, not a single ocean nearby. No one saw the sea. Never thought the world would go faster and shrink the time we had in it because then they began to disappear.

I only ever saw them as people alive. Sweeping the front step, smearing Windolene on the windows while they washed their nets in bleach, those Arkwright kids sucking rhubarb stalks while they made motorways in the gutter. Back then, those days never slogged like hearses on motorways, barges on locks. We made stuff up when life wasn’t exciting enough. We built new lands. We went there in gravy boats. But we always had a reason to come back.

258 people, 258 names. No one sweeps the front step any more. Like a multiplex this road with everything on show. You can see what they’ve got but you can’t call them by name. Children, you wonder – where have all those rhubarb children in gravy boats gone? 258 people, 258 stories. I could tell you many as now I can tell you none. We used to write stories with rhubarb stalks while our mothers swept the front step, boiled the nets, and wept at the kitchen sink.

We had a war and numbers 33 and 53 were lost at sea. That was their story. They went to sea to see what lived beyond the street, liked it so much they never came back. That’s what mother said. Winifred Waters said they did it for us.

Our closest ocean was the bathtub. When our mother didn’t cry, we made boats for the kitchen sink. ‘Where’s your boat going?’ she’d ask.

‘Not where those men went,’ I’d say. ‘Our ocean’s got sides.’

‘Don’t listen to Winifred Waters,’ mother warned. ‘She’s always been a wet weekend.’

258 people, 258 names. They forget I know their stories. We all paddled in the same ocean. Just because the road’s changed doesn’t mean I’ve stopped remembering. The last of the 258 we are. Him gone from next door, her over there gone snooty: we all had boats that sunk in the kitchen sink. Never occurred to me I should jump over the side, jump ship. I like sides. Wouldn’t like to be seasick, and numbers 33 and 53 jumped over the side. Wouldn’t do it for us now. The ocean’s full of lonely old fish looking for a mate or to be hooked up for dinner.

A great tidal wave should come down our road. That’d startle them. Let the ocean do its cleaning of the front steps, nets and gutters, because 258 people once, 258 stories, and no one would come out of their front door and save me. No one wants to hear my story. Winifred Waters would. She’d say, ‘All motorways lead to the sea, duck. That’s where they’ve gone and they’re not coming back.’

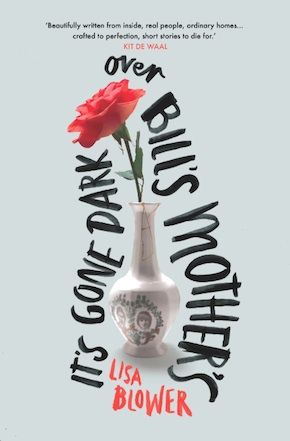

from It’s Gone Dark Over Bill’s Mother’s (Myriad Editions, £8.99)

Lisa Blower won The Guardian National Short Story Award in 2009, and was shortlisted for the BBC National Short Story Award in 2013 and longlisted for The Sunday Times Short Story Award in 2018. Her fiction has appeared in The Guardian, Comma Press anthologies, The New Welsh Review, The Luminary, Short Story Sunday, and on Radio 4. She is a contributor to Common People edited by Kit de Waal. Her debut novel Sitting Ducks was longlisted for The Guardian Not the Booker 2016, and shortlisted for the inaugural Arnold Bennett Prize 2017. She is a creative writing lecturer at Bangor University, where she studied for her PhD, and lives in Shrewsbury. Her debut story collection It’s Gone Dark Over Bill’s Mother’s is published in paperback by Myriad Editions.

Lisa Blower won The Guardian National Short Story Award in 2009, and was shortlisted for the BBC National Short Story Award in 2013 and longlisted for The Sunday Times Short Story Award in 2018. Her fiction has appeared in The Guardian, Comma Press anthologies, The New Welsh Review, The Luminary, Short Story Sunday, and on Radio 4. She is a contributor to Common People edited by Kit de Waal. Her debut novel Sitting Ducks was longlisted for The Guardian Not the Booker 2016, and shortlisted for the inaugural Arnold Bennett Prize 2017. She is a creative writing lecturer at Bangor University, where she studied for her PhD, and lives in Shrewsbury. Her debut story collection It’s Gone Dark Over Bill’s Mother’s is published in paperback by Myriad Editions.

Read more

lisablower.com

@lisablowerwrite

Author portrait: Bangor University