Opportunity

by Charlie Hill

“Mordant, touching, and – uniquely for a work of autobiography – entirely without vanity.” Jim Crace

A proper job! At Waterstones! I’m thirty-one! Now I have a debit card and everything!

But only just. On probation, I arrive three hours late after spending a night in a patch of nettles in Cannon Hill Park (Spiritus/Poles). After running a spike a long way into my flip-flopped big toe on the building site of the new Bull Ring (short cut/high jinks), I bleed up-and-down the shop for two days. Children’s laureate, Jacqueline Wilson, comes in to do a signing, finishes her stint and joins me in waiting for the lift. With her is the store manager, who is holding a plate of triangular sandwiches. Erroneously thinking our guest has eaten, I take a bite out of four of them, one after the other, bulging my cheeks and making Homer Simpson noises for comedic effect. I put the crusts back on the tray and grin as Jacqueline Wilson’s mouth drops open, my gaffer’s too, and I decide – shitters! – to take the stairs. Later, I’m called into the manager’s office to account for my recalcitrant timekeeping and am reminded that I once suggested there had been an anthrax scare on the number 50 bus.

However. Every time I have a staff appraisal, I skim the retail section and crib a phrase: ‘First Mover Advantage’ gets me moved up a grade and after ‘Retail is Detail!’ I am in charge of a team and encouraged to go into shop management.

I consider the offer. The store manager is an ex-punk and friends with Stu-Pid (lead singer of Police Bastard). The key word is ‘ex’: there is nothing punk-like about retail and although I have never been into punk, I like to think I might be punk-like, and decline.

—

All of the novels at Waterstones’ front-of-store look the same, and appear to follow some sort of formula. I’m not sure any of the other thirty would-be novelists who work there have noticed this, but I think it worthy of a story – my second – which is accepted by Ambit (part-edited by J.G. Ballard!) When the story comes out I decide to turn it into a novel about books; even though I don’t know how, I know it starts with writing, so I write.

—

I live next door to a pub in Balsall Heath, the Old Mo, which has a pool table upstairs. One night I run out of money and people to tap – a regular occurrence! – so I suggest a tournament, two quid in, winner takes all, for which there are twenty takers. I organise the competition over two nights – a couple of rounds there-and-then and the semis and final the following week – and spend the forty quid. In the final I am skint and go two down in a first to three, and have to work hard to avoid a beating, in both senses of the word.

I finish my novel about books. It has taken me a long time. I try to get it published and am buoyed by the responses of publishers who don’t publish it. I start a second novel, based loosely on my twenties in Moseley.”

I am living above a bookies in the Parade, Kings Heath. Me and my housemate, who deals drugs and collects superhero figurines and old games like Ker-Plunk in their original packaging, haven’t the money for our rent so we bet three hundred quid on England winning a football match – about which we know nothing – which they do in the last minute.

One afternoon, I take a call. “Bloody hell,” I say as I hang up, “that was the Independent on Sunday. I offered them one of my reviews last week and they want it.” A minute later, my housemate takes a call. “Bloody hell,” he says as he hangs up, “that was the Tweenies. They’re playing the NEC and they need eight grams of coke in forty-five minutes.”

—

Denny was a security guard at Waterstone’s and everybody loved him because he was smiley and quite possibly the only black man they had ever chatted to. He complained of a bad back for a week and then died of a heart attack. There was a three-line whip for the funeral but I wasn’t good at such things and didn’t know him well enough to go, a decision that was remarked upon in a subsequent staff meeting. “Thanks to everyone who came to Denny’s funeral,” said the manager, “it’s a pity not everyone could make the effort.” After I’d thought about this comment for a while – was it to do with strengthening our corporate identity? An observation on the right way to grieve? – I realised it was wrong.

—

I finish my novel about books. It has taken me a long time. I try to get it published and am buoyed by the responses of publishers who don’t publish it. I start a second novel, based loosely on my twenties in Moseley, during which time I heard much talk of The Great Moseley Novel; whatever else, my effort will not be that.

I finish my second novel in about a year and find a small publisher for it. I have no aptitude for design and help to design the cover but it doesn’t matter, I am now a novelist.

There is a lot of curmudgeon surrounding my publication deal, some of it from those who have me down as an incorrigible pisshead, some of it from those who talked in the past about writing The Great Moseley Novel. “It won’t change anything,” says an old friend and writer, and although this is curmudgeonly and the papers like my style, it is almost certainly veracious too.

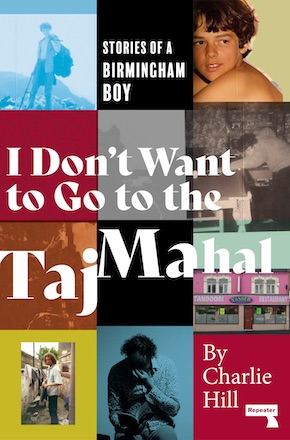

From I Don’t Want to Go to the Taj Mahal: Stories of a Birmingham Boy (Repeater Books)

Charlie Hill lives in Birmingham and writes novels, short stories and memoir. He is the author of Books, The Space Between Things and Stuff, and the founder and director of the PowWow Festival of Writing. I Don’t Want to Go to the Taj Mahal is published by Repeater Books in paperback and eBook.

Charlie Hill lives in Birmingham and writes novels, short stories and memoir. He is the author of Books, The Space Between Things and Stuff, and the founder and director of the PowWow Festival of Writing. I Don’t Want to Go to the Taj Mahal is published by Repeater Books in paperback and eBook.

Read more

charliehill.org.uk

@RepeaterBooks

Author portrait © Kevin Thomas