Escape

by Daniel Saldaña París

“Light-hearted and ironic but also vulnerable and transparent, Saldaña París’ language explodes in the reader’s face: a flash of lightning.” Valeria Luiselli

Teresa was, on the whole, a serious, earnest woman, with a slightly uneasy smile that barely lifted the corners of her mouth. Her black eyes always seemed to be trying to wrest a secret from the person they observed. She had a thick mane of hair with a streak of grey on the right temple. Despite the fact that my father insisted on buying her dresses and skirts in pastel tones and chic fabrics from Liverpool or Sears, my mother continued to wear the jeans, brightly coloured blouses and huipils that were the uniform of what she’d been before she met him: a seventies UNAM political sciences student. Her only make-up was a discreet black line on each eyelid (I’m discovering that fact now, looking at photos; my memory, as everything that follows here, depends on secondary sources).

She met my father at a party they both used to refer to in conspiratorial tones that made me feel excluded. I’ve never known for sure, and even as an adult it embarrasses me to ask, but I’m pretty certain that my mother hadn’t planned to become pregnant with Mariana in her final year, and that the pregnancy was the reason why she dropped out of university. The dates fit this hypothesis. My father, who studied economics, must have insisted at the time that a degree in political sciences wasn’t going to be much use for anything anyway; even at the age of ten I was well aware of the workings of his unsubtle mind, and that’s something he would very probably have thought in the seventies and continued to think to the end of his days, impermeable to any form of change that wasn’t for the worse. My theory is that my father was capable of holding contradictory notions: those aspects of Teresa’s nature that he found most appealing were also the ones he’d have done everything in his power to modify. He’d fallen in love with an independent, politicised student, but then he wanted to shackle that independence with the yoke of marriage and motherhood. He wanted Teresa to have her own opinions, but only so he could oppose them, brush them aside with a gesture of smug arrogance. He was like an entomologist who becomes enamoured with the flight of a butterfly and then decides to stick a pin in its abdomen. I’m shocked to admit it, but I too have loved in that way: almost unconsciously seeking the annihilation of all I desire.

This is pure inference, but it seems to me likely that, with time, the renunciation of her studies weighed heavily on Teresa. It can’t have been easy, after the mists of first love had cleared, to discover that my father was more unremarkable than likeable, and that the life of a housewife in Colonia Educación was in fact grim, completely lacking in interest and devoid of any historical sense. If she still read the newspaper from front to back every day; if she continued meeting her university friends from time to time (they told her about their master’s degrees, PhDs, and public-sector jobs); if she took part in the rescue efforts that followed the 1985 earthquake, leaving me, a two-year-old at the time, in the care of my grandmother for several days, it was because Teresa was doing her best to resist becoming the conventional housewife my father and society at large expected her to be.

During the months before her disappearance (her flight), Teresa had got caught up in ever more bitter disputes with my father… it was not unusual for my father to burst into a screaming rage.”

Teresa continued to go to demonstrations during the first years of Mariana’s life. My father’s reaction to these activities varied. At times he smiled, as if the tenacity of Teresa’s political commitment were a loveable trait; at others, he became exasperated and told her to stop wasting her life. She joined committees and went door to door in Educación collecting funds for Nicaragua, El Salvador and Guatemala. The neighbours were suspicious of her, and the local traders commiserated with my father for, they said, having married such a meddlesome woman. Then Teresa got pregnant with me, and that seemed to calm her a little. A complication in the pregnancy meant she was confined to bed for almost four months, and my father, secretly relieved, hired a woman to prepare meals and collect Mariana from school in the interim. My arrival in the world involved a – partial – capitulation for Teresa. Since I was a rather sickly child, my mother exchanged support committees for paediatric clinics, demonstrations for sleepless nights. Her work in the brigades after the earthquake of 1985 was, in some way, the swansong of her political fervour, which was then extinguished or went into hibernation for nine long years.

During the months before her disappearance (her flight), Teresa had got caught up in ever more bitter disputes with my father. While the violence was contained, the mutual contempt never explicit, it was not unusual for my father to burst into a screaming rage when he couldn’t have the last word. From 1st January of that year, with the appearance of the Zapatista National Liberation Army and the signing of the North American Free Trade Agreement, their positions had shifted in radically opposed directions. For my father, who worked in the agricultural and fishing loans section of a national bank, the arrival of NAFTA was an event that could only be equated with the second coming of the Messiah. Teresa, for her part, had her hopes pinned on the indigenous uprising in the Chiapas Highlands.

The residents of the middle-class, conservative neighbourhood where we lived seemed to fall in with my father’s convictions, and it very soon became apparent that Teresa had no intellectual ally in that homogenous context. I used every means at my disposal to become that ally. I privileged reading over sports, constantly attempted to contradict my father, and feigned an interest in the issues that Teresa thought were important – something very unlikely in a child of ten. And that’s why I felt frustrated when, despite all my efforts, my mother’s sympathies always seemed to lie with Mariana. It was to her she turned when she was heaping abuse on the government, as she frequently did. It was as if Teresa’s teachings were only directed at my sister – as if she knew I was already a lost cause, condemned to march in the enemy ranks. In recent times, I’ve shared those memories with Mariana, and she’s assured me that I’ve got it all wrong, that Teresa spoke to both of us, and if her efforts to indoctrinate Mariana were greater, it was because she was older and understood the arguments better. Although it has a ring of truth, this explanation seems lacking: I grew up with the unmistakable sensation of not being the favourite, perhaps because my father’s delight at the birth of a son ruined me forever in Teresa’s eyes.

Over the years, I’ve often wondered why Teresa didn’t talk to the two of us before she left. Or at least to my sister. For my part, I can now perfectly understand the reasons for her escape bid, and I long ago came to some form of peace with the fact that she’d decided to change her life, leaving me behind like one more element of a world that was no longer enough for her.

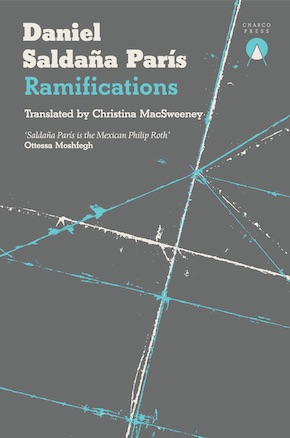

From Ramifications, translated by Christina MacSweeney (Charco Press)

Daniel Saldaña París, born in Mexico City in 1984, is a poet, essayist and novelist, considered one of the most important voices in Mexican contemporary literature. His debut novel Among Strange Victims (En medio de extrañas víctimas, 2013) was a finalist for the Best Translated Book Award and his follow-up novel Ramifications (El nervio principal, 2018) has brought him even more praise and admiration in Mexico and abroad. He has two poetry collections and his work has been included in several anthologies. In 2017, he was chosen as one of the authors of Hay Festival’s Bogotá39, a selection of the best Latin American writers under forty. He has been a writer in residence at the MacDowell Colony, Omi International Center for the Arts and The Banff Center, and was a recipient of the 2020 Eccles Centre & Hay Festival Writer’s Award. He has lived in Cuernavaca, Mexico City, Madrid and Montreal. Ramifications is published by Charco Press.

Daniel Saldaña París, born in Mexico City in 1984, is a poet, essayist and novelist, considered one of the most important voices in Mexican contemporary literature. His debut novel Among Strange Victims (En medio de extrañas víctimas, 2013) was a finalist for the Best Translated Book Award and his follow-up novel Ramifications (El nervio principal, 2018) has brought him even more praise and admiration in Mexico and abroad. He has two poetry collections and his work has been included in several anthologies. In 2017, he was chosen as one of the authors of Hay Festival’s Bogotá39, a selection of the best Latin American writers under forty. He has been a writer in residence at the MacDowell Colony, Omi International Center for the Arts and The Banff Center, and was a recipient of the 2020 Eccles Centre & Hay Festival Writer’s Award. He has lived in Cuernavaca, Mexico City, Madrid and Montreal. Ramifications is published by Charco Press.

Read more

@CharcoPress

Author portrait © Ángel Valenzuela

Christina MacSweeney received the 2016 Valle Inclán prize for her translation of Valeria Luiselli’s The Story of My Teeth, and her translation of Daniel Saldaña París’ Among Strange Victims was a finalist for the 2017 Best Translated Book Award. Other authors she has translated include Elvira Navarro (A Working Woman), Verónica Gerber Bicecci (Empty Set; Palabras migrantes/Migrant Words), and Julián Herbert (Tomb Song; The House of the Pain of Others).