Not for the ordinary reader

by Mika Provata-CarloneÉmile Zola thoroughly enjoyed being the bête noire of French letters and the gadfly of the literary imagination, constantly challenging what writing, novel writing in particular, was all about. He was unflinching in his project of redefining literature as an enterprise of scientific scrutiny into society’s innards and gutters. He became the leading figure of the Naturalist movement in France, intent on bringing together the aesthetic style and artistic agenda of artists like Édouard Manet (who painted a full-figure portrait of Zola’s Nana) and philosophers such as Hippolyte Taine, who proclaimed that the environment played a critical role in the formation of character and society, or Henry Bergson, whose élan vital, the vital impetus in every living being, Zola reinterpreted in his own version of joie de vivre. Also, and especially, of pioneering scientists, such as Claude Bernard, who offered breakthrough insights (or false leads) into the physiology of endocrinology and neurology – models of human laws and life.

Following their cue, Zola’s project in literature was the objective and detached observation of social behaviour and mores, the formulation of hypotheses as to their reasons and origins, identifying mechanisms and causal factors. Literary writing in his hands took on the full potential of stylistic experimentation (colloquialism, chiaroscuro, tonality and rhythm, striking characterisation and radically innovative plots), but above all it became a document of human systematisation. Zola aspires to a physiological analysis of society – not merely its individuals, the typical subject of novels, but of crowds, of clans, of the human masses making themselves poignantly present and vocal at the height of the industrial revolution, as a result of social change and educational reforms in the Second Empire in France and Edwardian England across the channel.

As the Goncourt brothers would write in their diary, Zola’s battle cry was “C’est du Darwin! La littérature c’est ça!” – literature is a Darwinian exercise. Or, as Zola will say more succinctly on repeated occasions, “l’homme métaphysique est mort, tout notre terrain se transforme avec l’homme physiologique” – there are no metaphysics, only physical reality and realism. The body and its urges, the primeval instincts and drives of man and society are his targets and themes, Zola wants novels that have “l’odeur du peuple” – the smell of the people. This was fiery stuff in the late 1800s, and this scent of the many did not appeal to all.

With weightless erudition and engaging sensibility, Horne guides us to think on the purpose of writing, the ethics of reading and publishing, the responsibilities of the artist towards himself, his art and society.”

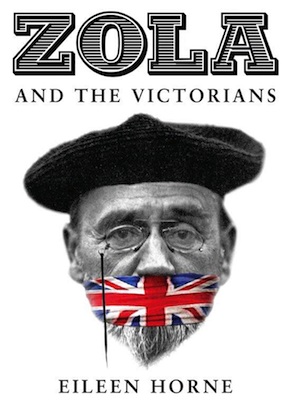

The British reaction to Zola is the framework of Eileen Horne’s masterly and gloriously readable Zola and the Victorians. Her central themes are writing as a creative act, the writer and his human cosmos, the practicalities of writing for a public audience: putting a price on words, profit versus morality, authorial and translators’ rights, copyright (a very new and nebulous concept at the time), and publishers, that new breed of divine messengers or fiendish traitors. Horne conjures up a scintillating image of the times, of the contrast between public personas and private lives. Zola had famously written in an essay on art “if you ask me what I came to do in this world, I, an artist, will answer you: ‘I am here to live out loud’” – a spirited aphorism that will be taken up by almost every maverick or not so maverick generation that followed. As Horne powerfully yet gently points out, Zola writes out loud, yet lives “a muffled and dull private life”.

With weightless erudition and deeply engaging sensibility, Horne gives us a vivacious history of modern publishing, she resurrects seminal forgotten lives, such as the Vizetelly family, and guides us to think, without prescribing our thoughts, on the purpose of writing, the ethics of reading and publishing, the responsibilities of the artist towards himself, his art and society. She demands that we take a stance with regard to what constitutes literature – and whether as readers, writers or critics we have a right (or a duty) to ask the question at all.

Horne’s book moves with dynamic pace across five years starting with the leap year of 1888, the year of the three emperors in Germany, a year of colonial acquisitions and expansions that saw the foundation of mythical empires of wealth such as De Beers, a year of promises and the furthering of women’s rights. Also a year of natural disasters across the globe, Homeric cricket wickets and the formation of the Lawn Association, the first motion picture, and social uprisings in both France and Britain. It is the year when Pessoa, de Chirico, T.E. Lawrence, T.S. Eliot, Kate Mansfield and Eugene O’Neil are born, and the year when Edward Lear, Louisa May Alcott and Matthew Arnold die. The year of Oscar Wilde’s The Happy Prince and Other Tales, Henry James’ The Aspern Papers, Hardy’s Wessex Tales and Kipling’s Plain Tales from the Hills. The year when Van Gogh cuts off part of his left ear and Bismark talks of war in the Reichstag. In London, it is the year when the Whitechapel murders spread terror in the city’s streets and two forgotten literary trials warp the course of publishing (until, as Horne describes with fine drama in her coda, 1964).

While George Moore denounces reporters writing on Jack the Ripper for their “pornography of violence”, the publishing firm of Henry Vizetelly is prosecuted for feeding the “moral decay that is a danger not only to our youth but to the very roots of our empire” according to H.H. Asquith. By publishing Zola’s novels in affordable editions, the firm is accused of profiting from “selling impure and corrupting literature of the most pernicious kind”. The accusation comes from the National Vigilance Association, an organisation as pristine in its proclamations of morality as it was ambiguous in the selection of its targets. Their previous prey had escaped their nets: Boccaccio’s Decameron had been exonerated on the basis of antiquity and the fact that a copy was to be found in the British Library. Vizetelly’s defence will be “a storm of books” evoking literary precedents of liberal expression, such as Byron’s Don Juan or Shakespeare’s The Merry Wives of Windsor. They could have as easily evoked James Gillray’s “savagely satirical, unblushingly scatological style”, as the ART Quarterly will summarise it, or Hogarth’s famous infamous caricatures, Henry Fielding or Jacobean drama. The N.V.A. will not admit failure a second time, and attacks ruthlessly. At stake, on both sides, is what they each call “the principles at stake: the future of publishing”, and especially, again for both accusers and accused, England and Englishness.

The liberation of the mind of the reading public is pitted against what is perceived as the need to control the reading habits of the lower classes by making certain books prohibitively costly, with right and wrong amply distributed to both sides. Not only what could stereotypically be called elitism, but also racism is at the crux of the matter: in France Zola is the Italian perverter of morality, in England so is Vizetelly, with his Venetian ancestry. Translation, that new force of communication and unification, is brutally blamed for introducing novel spirits, the demons of modernity (we hear unmistakable echoes of the trial of Socrates), and also for lowering aesthetic standards: the base line of the accusers is to denounce the translation of Zola’s works as an unworthy process, that “can only feebly plead the privilege of art”.

It is quite amusing to see the English sticking up for a Frenchman and to wonder whether the French would have done as much were the tables turned.”

“What is realism?” is a central question in this high-spirited and brilliantly assembled book, which explores both salaciousness and genuinely objective reflection with intrepid vividness and truly absorbing scholarship. This is a serious inquiry into its themes, a mesmerising portrayal of the society of Victorian men of letters and morals. Horne has the gift of creating the story of real events without reducing them to fiction, yet also without falsifying their reality. Zola and the Victorians reads like a novel and feels like life, captivating from first to last page, including the thriller-like coda and the particularly illuminating chronological ‘ironing out’ of the saga of the Rougon-Macquart, Zola’s microcosm and his English publisher’s nemesis.

It is quite amusing to see the English sticking up for a Frenchman and to wonder whether the French would have done as much were the tables turned. Horne wants us to sense such ironies of fate or human choice, giving us sharp characterisations of the human characters involved: she quotes Zola’s claim that with his new mistress he is now a man “ready to devour mountains”, juxtaposing him to Henry Vizetelly, who at that very moment, is the man “tired of existence”. She also wants us to be piercingly aware of the ironies in the social and human situations as she creates a chiaroscuro narrative of Zola’s success and triumph in England at the end of Vizetelly’s life and the ruin of the latter’s career and fortune. Hypocrisy is rampant, as exclusive and expensive limited editions do not seem to fall under the strictures of the seminal decision of the Zola/Vizetelly trial, which leads to the literary phenomenon of the Englishman abroad: Paris becomes in Edwardian times the place for British expat publishers who can produce books otherwise prohibited by English law. Fin de siècle England will make possible the Paris renaissance of the early 20th century for writers, artists, musicians.

Horne has written an infinitely enjoyable and irreplaceable book, not only about Zola and his English publisher, their lives and times, but also about the precepts and principles of all writing, as well as about the need to reassess our perception of and attitudes to how books become objects of desire: about the thrill or cult of marketing. Throughout Zola and the Victorians Horne reminds us that “it is not just the N.V.A. and their ilk that are eroding the boundary between art and pornography… publishers are responsible for the way their books are promoted”. Which leads to the silent thunder in Horne’s book: Zola was not simply a bawdy writer, but a Darwinian dramatiser of human life. His naturalism resonates strongly with determinism, and at the antipodes of this determinism is of course the cult of individualism, the precept that men and nations can define their destiny. At the peak of colonialism this is a credo that must remain unassailable. Attacking Zola was not simply a defence of middle-class morality (or morality pure and simple). It was an expression of the titanic clash between Darwin and Machiavelli, man as a garbled predetermined net of nature’s forces and drives or man as the Prince, the self-motivated lord of nations and the cosmos. Horne’s analysis subtly enhances these tensions, and her own dramatisation is full-blooded and calm at the same time, a very human look into a powerful drama. Zola and the Victorians is a book to relish, a thinking book, and immensely enjoyable.

Eileen Horne was born in California, relocating to Rome and then to London in the late 1980s. She has spent twenty years in the independent television sector, founding her own production company in 1997 and making over a hundred hours of primetime drama, among them two projects inspired by Zola’s novels. She now combines her writing activities, including adaptations for radio and television, with work as a post-graduate tutor. Zola and the Victorians is published in hardback by MacLehose Press. Read more.

Eileen Horne was born in California, relocating to Rome and then to London in the late 1980s. She has spent twenty years in the independent television sector, founding her own production company in 1997 and making over a hundred hours of primetime drama, among them two projects inspired by Zola’s novels. She now combines her writing activities, including adaptations for radio and television, with work as a post-graduate tutor. Zola and the Victorians is published in hardback by MacLehose Press. Read more.

Buy at Amazon

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.