Origins

by Chris Emery

I LIKE ORIGIN STORIES, especially how a writer came into their powers. Whose life was swept away with a memo from Personnel. How that GP’s news became a license to write stories about divorce. Filthy jobs and warehouse nights. Squats and baggies and needles. That sort of thing. Of course, for some it was all foreign castles: an address book filled with dignitaries and benefactors. These days, most origin tales probably involve a low-ceilinged lecture room in the Victorian north, listening to three guest agents talk about six-way auctions and royalty steps. Or talking about contact hours with Dr Hines from Life Writing.

When I was a teenager, to be a writer meant suffering from something – consumption, loneliness or communism – this sort of thing. I mean, there were the glorious suicides queuing up for us in the glossies, or so it seemed, or the odd Times piece about a fellow permanently in his cups, knocking back the last of the Tesco’s vodka, writing something about sink estates and shagging. In the weekend papers you might catch sight of a puff piece with a large plate photo of some grand vizier (and FRSL) sitting in furs on the Getreidegasse, sipping an Einspänner, reading the Salzburger Nachrichten for news of Brezhnev and the recent T-64 manoeuvres – their new novella is described as ‘quixotically mitteleuropäisch’, which you needed to look up later in your battered red Collins dictionary.

Writers had exotic lives in the 1980s (where my own past continues to live), I suppose now we have marking and research leave, or provincial tours to manage – which must be some sort of progress, I’m not sure. The thing is, it doesn’t matter where you start, and most writers do lead rather banal lives. They must still replace fuses, nip out for a pint of blue milk, or have the cat checked for ear mites.

In some way, I have a kind of grief about all this – once upon a time, to be writer was to be set apart from the world, not above it, but beside it; it gave one the freedom to comment on the awful inequalities, or the coming nuclear winter, greed and sin, and much else besides. It had natural glamour, of course, and it had gritty romance. Back then, migrants were émigrés, and much to be admired, dodging bullets to fetch up in Venice, escaping the reds. It really does seem awfully more interesting than the dire wolves-and-fairy sex that peppers successful publishing today, but I’m being snarky now, and I’m getting old. Maybe origin stories have shifted for the kids, maybe they’re all into AI now. AI is certainly into us.

Writing is, at its most revealing, about an author’s sensibility. Texts from life. Plein-air writing, so to speak. One must have a life to write.”

I mention all this as I was back in the north last week, wandering around Moston Lane East and Hollinwood Avenue in Manchester considering my childhood – that lax eternal space where nothing much happened – well, Catholicism, gangs and beatings, perhaps – and I was staring at bin overspill and wan buddleia by a scuzzy railway embankment, idly thinking, Was it here it all began?

Everything starts somewhere, I suppose. These days we focus a lot on the mechanics of writing – you know, third person singular, POVs, prompts about vitiation – but I rather think, after many decades trying to avoid thinking about it much at all, writing is, at its most revealing, about an author’s sensibility. Texts from life. Plein-air writing, so to speak. One must have a life to write.

I read all the theory once, and have certainly considered the death of the author, the isolation and interrogation of the text, its contradictions and fault lines, bleeding it all dry. But I look in the mirror and there I am, still having all this life stuff going on. Rooted, if not exactly rooted to the spot.

Having experience then is quite important for a writer. In fact, my advice is very much to get out there and have some of it: life that is. I’m not denying the power of imagination here, I know about The Red Badge of Courage, but so many young writers miss out on the thrilling drudgery of being in the world – selling bad suits down the market or decorating HMOs with tubs of magnolia for some grubby landlord for a few quid. Jobs. I think writers should, now and then, occupy the world of work and approach it with clear intent to get it down onto paper and offer it all back to us. And this is because it is the world of our readers. Non-synthetic, grubby, unassimilated, gorgeous readers. We must get out into the mess of it all. Not to belong, but to coolly observe. Or at least endure.

Out there, walking from TK Maxx to Superdrug in the drilling rain, checking in with Karl on whether there are still chicken nuggets in the freezer for Laveya’s fifth birthday party at Rockers ’n’ Rollers later. I guess I’m saying that origins are all around us, suspended in the lost stories of ordinary lives, gliding by like midday fog between the boarded and unboarded buildings, beyond money, beyond endeavour, beyond meaning or morality. Anyway, let me tell you a short story about origins…

The handover

OUR STAN AND I are squatting in a pub on Oxford Road, you’ll know the place. We signed on yesterday so today is drinking day. Another one, naturally. It’s quarter to two, a black-and-white screen by the beer taps shows the credits for Pebble Mill: silent, fuzzy, the show now over.

Through greasy, mullioned windows, we can see Manchester’s BBC studios: plateaux of white concrete stretching away. It’s raining; it’s been raining for several days. Thick curds of water boil in the gutters, running all the way down to All Saints and the first beggars and buskers. Our Stan is sort of visiting, but I live here still, four miles north of the centre. We’ve been at it all day now. Drinking.

I can see the sky outside is pewter, but we’re in here, knocking back two more pints of weak Boddies by some kind of table football game – its little blank-faced players are chipped, twisted at angles on their poles, but we barely notice this. We are talking about boring Frederic Leighton and his biblical pornography, Chesney Hawkes, Lenin’s big potato head, Belgian esprit de corps, that sort of thing, when the two of them arrive.

At first, we think we must know them. I mean, they head straight towards us – underweight, limping: Jez and Tab. Jez is wearing a green, torn kagoule, red cords and Kickers. Tab has on a sooty red lumber jacket; his trousers are the colour of week-old stew. He’s wearing Pods that have seen better days.

‘Budge up, Mate. C’mon, shift yer arse.’ Jez is smirking. We’re about to have fun, I guess. I smile back at them both; but I can’t hear properly. They must want to play on this thing. I look down at the smooth-featured players, upturned, diving.

‘Sorry, Pal?’ I say. ‘What’s that?’

‘Budge up.’ He’s sitting beside me now, almost on top of me; but the smile has gone.

Then Jez pulls out his hunting knife and rests it on my thigh. I look at it and then slowly lift my face to his lifeless eyes. He presses up against me. I can smell bacon and sweat.

‘Keep on drinkin’ and don’t fucken move or ahl jib yer.’ He looks at the greasy glass table top. Looks at our glasses. ‘Fucken Boddies, Lah? Boddies? You dickheads.’

Tab takes out a homemade bradawl wrapped in insulation tape. All the time, he keeps his eyes on us and begins working a metal slat loose at the side of the table. His eyes switch between our Stan and me. Back and forth, back and forth. He doesn’t speak. He has thin ginger whiskers on his pitted face.

‘Keep yer fucken mowves shut,’ says Jez. ‘Get ready to shift yer arse, you’re bowf gonna come out wiv us, right. Just ’ang on a minnit, ’ang on.’

Tab has the steel panel off now and is pouring coins from a black tray into a sports sock. He pulls another sock from his jacket. He fills three socks while staring at me. He shakes them, ties them, and pockets them.

I can see there isn’t another soul in this place. No one is serving. No one else is drinking. The bar stands empty like a bad mouth of glass and mirrors. The whole place is in sweaty, beery twilight, swooping with lights from quiz machines, chirping and gurgling at every corner. I feel my stomach tense. My ears seal up and start to ring.

‘Ged up. Ged up, now. Fucken move, Lah.’ Jez has his hand in the small of my back as we stumble between heavy teak stools, over-padded stools, and eventually reach the swing doors and step out. The air is biting. The four of us are blinking in the last overhaul of city rain.

He grins as if we have been initiated into something dirty, something small and true. We cross the street and obediently walk away.”

There are quick shoves, shoulder to shoulder, along the road, as if we’re trying to march somewhere out of time. All the while, I’m staring at Tab and Tab is staring back at me. Mute Tab. Watchful Tab. We are ushered along to the corner of Whitworth Street, just below the Cornerhouse gallery. We stop as lines of traffic crawl to a halt by the lights. Tab reaches over to me with something in his hand. I tense for it. Yet he lifts my hand, and I briefly feel his wet skin. He pushes something into my palm – it is five pound coins that I see there. I blink at them, suddenly vacant.

Jez squawks now, ‘Get a lick on. Go on. Don’t fucken ’ead back ’ere or ahl fucken gut ya.’ Then he grins as if we have been initiated into something dirty, something small and true. We cross the street and obediently walk away.

We walk along the wounded pavement, taking quick steps like infants. Past the Palace and the Refuge, twisting our hips this way and that, looking back over our shoulders at mordant lines of traffic, trying to see them, Jez and Tab, lost in the rain. We cross Princess Street and head past the New Union, only stopping to speak when we are halfway up Canal Street with its filthy red buildings. We’re alone now, back in the world.

‘Look,’ I say, but my voice has cracked. ‘Look.’ And I hold out my palm to show Stan the dull coins. He smiles back at me, snorting, and wipes his mouth on a sleeve. ‘We can do that.’ he says, stepping back, swinging out an arm. ‘We can absolutely fucken do that. Honestly, Baz. All day fucken long.’

I look up at our Stan now and find I cannot speak.

—

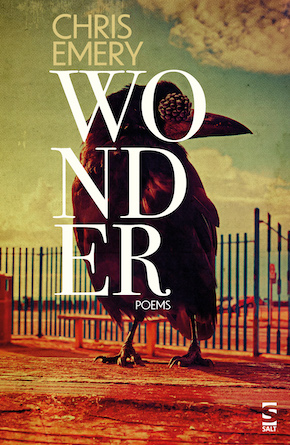

Chris Emery lives in North Norfolk and works in publishing. Wonder, his fifth collection of poems, is published in paperback by Salt.

Read more

chrisemery.me

@chrisemery.me

instagram.com/chamiltonemery

instagram.com/saltpublishing