Outback to the future

by Paul Howarth

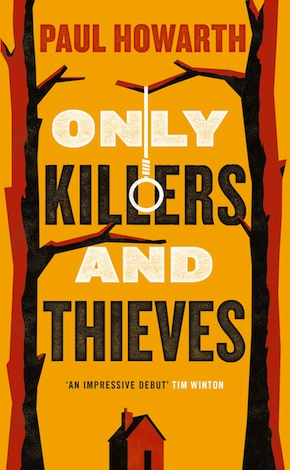

“The savagery it depicts is still a matter to be reckoned with in contemporary Australia… an impressive debut.” Tim Winton

I didn’t always want to be a writer. When I was at school it just wasn’t the kind of thing I thought you could ‘become’, or, even if it was, how you would ever go about doing so. This was pre-internet, a dark and mysterious time when the sum of all knowledge was the ragged family encyclopaedia, and the only contacts anyone had were those listed in the Yellow Pages or phone book. We didn’t know any writers. Like filmmakers, they seemed to belong to a different world, their work appearing in bookstores and cinemas by some kind of faraway alchemy I didn’t understand. Yes, I’d read early, had written stories at the kitchen table, and English was always my favourite subject, but the idea of actually becoming a writer was as fanciful as becoming an astronaut, if not more so – at least astronauts appeared in the encyclopaedia, and the shuttle launches were shown on TV.

Instead, I became a lawyer, and for a long time wrote no fiction at all; and, in truth, read far less than I would have liked. But – perhaps without even realising it – I was, in a roundabout way, honing writing skills that laid a foundation of sorts. I was working with words every day, constructing written arguments and narrative, as well as telling other people’s stories when drafting witness statements – first-person retrospectives delivered in an individual’s own voice, with their own style and point of view. In fact, I developed a bit of a reputation: my client advice notes, my supervisor once told me, were “pipe and slippers reads” – she would kick back in her chair and settle in, raising the note before her like a novel on a lazy Sunday afternoon. I enjoyed leading the reader through the various arguments and delivering a satisfying conclusion at the end. Even more enjoyable was the back-and-forth correspondence with opposing law firms; I remember one with such a killer last line it should have contained a thriller-style warning: “The shocking twist you’ll never see coming!”

The movie-version of this story is that I then sat down and wrote Only Killers and Thieves in a rapid blaze of inspired glory; that I, like the Karate Kid painting fences and waxing cars, had intuitively been learning the skills of an author without even realising it, and was now ready to crane-kick my novel fully-formed into the world.

I began my first attempt at a novel like a cross-ocean sailor in a dinghy: in theory I had the basic tools to get there, but it was going to be bloody hard work and take a bloody long time, or I’d simply sink along the way.”

Some movie. All in all, it has taken ten years. There are no short cuts when it comes to writing fiction: it can only be learned by doing, and by reading far more widely than a few paperbacks on holiday and a couple of pages before bed. In short, I had a lot of catching up to do. But I do think those years in the law firm helped. Stupidly, naively, the prospect of writing 80,000 words of prose didn’t daunt me, but the technical aspects such as structure, style, point of view… I didn’t know these things existed. I began my first attempt at a novel like a cross-ocean sailor in a dinghy: in theory I had the basic tools to get there, but it was going to be bloody hard work and take a bloody long time, or I’d simply sink along the way.

A couple of novels came and went. They weren’t terrible, they weren’t great. The rejections began stacking up, some more encouraging than others, but all amounting to the same thing: no. After a lot of work, one of those novels even came pretty close, finding an agent but no publisher, and though it was tough at the time, I’m very glad it didn’t. None of those books was good enough. None was what I really wanted to write; in fact, I don’t think I was capable of writing what I wanted to write back then. There was still a definite gap between the novels I admired and the work I was producing, a gap I wasn’t really sure how to bridge.

By this stage, I’d left the law job and moved to the other side of the world, living in Melbourne with my wife and (then) baby daughter, and had recently become a British-Australian dual citizen. I still believed in myself – and you must, because if not you, who else? – and still wrote every day, but the ambition of publication seemed to be getting no closer and I felt cut off from the publishing industry by an impenetrable wall. I wondered how much I had left in the tank, how much longer I could carry on before writing became a hobby and I got on with the rest of my life. At the time, I’d just finished and submitted a contemporary novel tapping into the history of Britain’s colonisation of Australia, the ‘wild west’ era of the Australian frontier, and the legacy that period had left behind. That was one of the books that didn’t quite make it – encouraging rejections, but the answer was still no. One said something along the lines of “its grasp doesn’t quite match its reach,” which perhaps summed me up as a writer too. But I was still very interested in the period and the history and continued reading about it for my own sake, which is how I eventually came across a reference to the Queensland Native Police.

Patrolling the nineteenth-century frontier in small detachments made up of a British officer plus a handful of Aboriginal troopers, the Native Police was an official yet shadowy arm of colonial power kept largely out of the record books and away from prying eyes on the coast, operating with impunity on the borderlands of white settlement and ‘dispersing’ Indigenous Australians however and whenever they saw fit. I was shocked, captivated, intrigued… but I’d just written an entire (albeit contemporary) novel set in rural Queensland covering similar ground, and didn’t feel able to embark on another. So instead I wrote a long story, 25,000 words, creating the characters of the orphaned young brothers Tommy and Billy McBride, the savage Inspector Noone, and the racist squatter John Sullivan, and sending them all into the outback on their misguided mission for revenge.

The idea of turning that story into a novel felt more challenging and daunting than anything I’d ever attempted before. Which was the whole point – if you’re not writing something that scares you, you’re writing the wrong thing.”

I wasn’t sure what I had written, or whether it could be anything more, but I used a section of that story for my application to the creative writing programme at UEA and, to my surprise, not only got in but was awarded a scholarship too. In my first meeting with my tutor, he asked what I was planning to do with “the Australian story.” Truthfully, I didn’t know. I felt ready to move on to other things, and the idea of turning that story into a novel felt more challenging and daunting than anything I’d ever attempted before. Which was the whole point, I think: I’ve heard it said that if you’re not writing something that scares you, you’re probably writing the wrong thing.

Two years, various drafts, and a master’s degree later, I hit send on the first round of emails submitting Only Killers and Thieves to agents, having researched them and their authors online. Suddenly their world didn’t seem so far out of reach this time, and not just because of the amount of information available to aspiring writers these days. By that stage I’d been chipping away at the wall for eight years, but was beginning to see cracks appear; cracks that maybe, just maybe, might be wide enough to slip my latest manuscript through.

And if that didn’t work out, then hell, I was only 38, maybe there was still time to give the whole astronaut thing a go.

Paul Howarth was born and grew up in the UK before moving to Melbourne in his late 20s. He lived in Australia for over 6 years, and now lives in Norwich with his family. He graduated from the UEA Creative Writing MA in 2015 and was awarded the Malcolm Bradbury Scholarship. Only Killers and Thieves is published by ONE, an imprint of Pushkin Press.

Paul Howarth was born and grew up in the UK before moving to Melbourne in his late 20s. He lived in Australia for over 6 years, and now lives in Norwich with his family. He graduated from the UEA Creative Writing MA in 2015 and was awarded the Malcolm Bradbury Scholarship. Only Killers and Thieves is published by ONE, an imprint of Pushkin Press.

Read more

@paulhowarth_