Tara Isabella Burton: My sister’s keeper

by Brett Marie

“A wicked original with echoes of the greats.” The New York Times

I have this friend on Facebook. Man, she just about glows in the dark. For the past five years, she’s been adding sparkle to my feed with posts about her opulent lifestyle. From the stream of articles she posts on her timeline (in Salon, National Geographic Traveler and Vox, to name just three), I’d say she’s a journalist by trade. But that’s not so much her profession as her secret identity. She roams the earth, seeking out exotic destinations for her travel writing, sniffing out weird people and intriguing stories on politics, culture and religion. But every so often, some sort of glam Bat-signal goes up over the horizon, and she’s off in pursuit of her real mission: to save social media from the evil forces of banality. Suddenly, her timeline becomes a stream of Instagram shots of her and an entourage of impossibly beautiful people, a kind of glitterati Justice League, posing at some lavish social function or other. Each photo is more fanciful and elaborate than the last. There she is in Elizabethan garb at a period costume party in Venice. Now here she is with her gang at the Pyramids, dressed like a band of 1920s Egyptologists.

Tara Isabella Burton: even her name could light up a room – like ‘Zelda Fitzgerald’, only more of a mouthful, as if she has too much glitter in her to fit in any less than eight syllables.

Most of the times that I see her pop up on my screen though, I scroll right past her. It’s not that I don’t appreciate her posts; quite the contrary, I find them fascinating. The photos are works of art, really: here’s this pretty young Manhattan socialite, dressed in whatever outlandish costume strikes her fancy that evening, with a coterie of friends decked out in similar fashion, forming a tableau vivant in which even the furniture seems dolled up for the occasion. But the glamour it gives off, it’s like staring into a naked 120-watt light bulb, and on instinct I tend to look away.

There’s another reason behind my skittishness, one which I find far more troubling. It’s that hint of queasiness that’s bubbled up somewhere in my chest when I’ve paused to read one or another of her status updates. Early in our friendship came Tara’s delighted post about Richard Dawkins tweeting a link to one of her articles discussing the value of religious studies. There was her announcement a year or two later that she’d signed with the Janklow & Nesbit agency, joining a roster that included Jeffrey Eugenides and Danielle Steele. And then there was the post expressing her excitement when Doubleday bought her novel manuscript (that one accompanied a photo of our heroine grinning beatifically at the email notification on her computer screen).

I don’t do self-pity, but over the same period that these bits of news have dropped, I’ve watched the trickle of emails, dozens of mostly form letters from agents and publishers rejecting my novel manuscript, drip-drip-dripping into my inbox. Though I like to think I have thick skin, the sheer number of these notes is enough to rub anyone raw, and switching over to Facebook, hovering for too long over those bulletins of another writer’s success, I can feel the sting of envy seeping in through that open wound. The only salve for it is to hit ‘Like’ underneath her posts, tap maybe a few words of congratulations into the comments, pat myself on the back for being so gracious, and scroll quickly away.

‘To the Holy Mountain’ was a drama of love and death, of friendship and loss, a story that toyed with the existence of God before snatching Him away and leaving my heart dashed against the paving stones of Tbilisi.”

I find it important to remind myself that her work merits all this success. A former Clarendon Scholar at Oxford’s Trinity College, she has a doctorate in theology and fin-de-siècle French literature under her belt, and her articles on related subjects carry all the authority that this implies. Her travel writing, which has led her to settings as varied as the milongas of Argentina and an all-night diner in Manhattan’s Chelsea neighbourhood, paints vivid pictures of her surroundings while also offering compelling snapshots of the real-life characters who cross her path.

And if that’s not enough, I have only to cast my mind back to my very first contact with her. In October of 2013, having just spent the previous month refreshing the Bookanista website daily to make sure my short story ‘Sex Education’ was still front-and-centre on the New Voices page, I logged on to discover that a new story, called ‘To the Holy Mountain’, by one Tara Isabella Burton, had taken its place. Feeling the warmth of the New Voices spotlight leave me for someone else, I chose to be magnanimous and proceeded to give this fledgling young talent a fair reading.

Thirty-five hundred words later, ‘To the Holy Mountain’ left me not so much magnanimous as utterly humbled. My story had joked around about bad sex in New York City. Tara had loftier goals, and chose instead the Caucasus Mountains in the Republic of Georgia for the backdrop to a drama of love and death, of friendship and loss, a story that toyed with the existence of God before snatching Him away and leaving my heart dashed against the paving stones of Tbilisi. As I recovered from the last line, a voice piped up in my head. “Well,” it said, “you fooled them for a month. Now they’ve found the real thing.”

Picking up the shreds of pride I had left, I decided I would be courteous to this fine author who, after all, was my peer. I shared ‘To the Holy Mountain’ on Facebook, topping it with the mild understatement: “Stunning.” I found an email address for Tara and sent her a note, congratulating her on her work, and telling her how much I’d enjoyed it. Her reply was friendly and thoughtful, just the type of note to dispel any sense of jealousy. Our Facebook friendship started about that time.

I like to think I’ve been a supportive Facebook friend. I’ve Liked plenty of Tara’s articles when they’ve appeared on my feed. I’m pretty sure I Liked the post about finding an agent. I hope I went to the trouble of typing out my congratulations when she shared the news of her book deal. I live with the distractions of a day job, my music and a busy home life, to which for some years now I’ve added the work of writing reviews and features as a contributing editor at Bookanista – and at any rate, I tell myself, with all the Likes she gets, Tara certainly hasn’t needed my voice adding to the booming chorus of well-wishers.

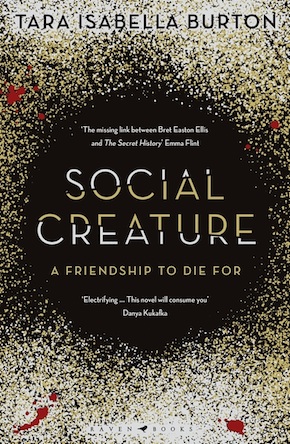

That brings us to this year. Of course when Raven Books starts sending out review copies of the UK edition of Tara’s Big Debut Novel Social Creature, I’m among the first to snag one. It seems only right, I tell myself, that I should be the one to give Bookanista’s blessing to its rising alumna. Receiving my copy, I smile at Raven’s choice of words for the inside cover: “Introducing a Brilliant New Voice in Contemporary Fiction.” Then I turn to page one, and meet Louise and Lavinia.

Louise is a lonely, failing writer working three jobs and living hand-to-mouth on the outer edge of Brooklyn, when circumstances bring her into the orbit of Lavinia, a beyond-wealthy young Manhattan socialite living in a luxury Upper East Side apartment. Taking a shine to Louise, Lavinia draws her into her world of fabulous parties and nights at the opera, of champagne and cocaine, of epic Bacchanalian revelry punctuated at regular intervals with bouts of selfie-posing and Instagram-posting. Under Lavinia’s wing, Louise finds herself at the centre of a hyper-privileged in-crowd, filled with members of New York’s literary elite, the gatekeepers to that world she’s been dying to enter for so long, who are suddenly eager to usher her in.

Lavinia fills Louise’s head with all the great things they will do together, and all the places they’ll go ‘when they are both great writers – to Paris, and to Rome, and to Trieste, where James Joyce used to live.’”

All of this comes at a price, of course: to keep up a lifestyle that is light years beyond her means, Louise depends on Lavinia’s continued generosity, and must submit to her benefactor’s whims and mind games. But all along, Lavinia fills Louise’s head with all the great things they will do together, and all the places they’ll go “when they are both great writers – to Paris, and to Rome, and to Trieste, where James Joyce used to live.”

All of this comes at a price, of course: to keep up a lifestyle that is light years beyond her means, Louise depends on Lavinia’s continued generosity, and must submit to her benefactor’s whims and mind games. But all along, Lavinia fills Louise’s head with all the great things they will do together, and all the places they’ll go “when they are both great writers – to Paris, and to Rome, and to Trieste, where James Joyce used to live.”

It seems foolish, as I devour the first few chapters of Social Creature, to draw parallels between fiction and reality. But it’s just too easy. I have a term for myself now: I’m a Louise. And what does that make Tara? It’s an uncomfortable line to draw, but when I reach her on Facebook for comment, she assents to my conclusion without much prompting. “I grew up in an environment a lot more like Lavinia’s than Louise’s,” she tells me, and though my parents raised me not to talk directly about money when conversing with friends, I do pick up hints of affluence when this child of the well-to-do Upper East Side tells me about her background.

Money is merely socially awkward; the comparison becomes uncomfortable as Lavinia spends a hundred pages apparently teetering on the verge of psychosis, engaging in passive-aggressive power plays to gain control over Louise. She has Louise move into her apartment, but claims she’s not allowed to have a key made, so that Louise depends on her to get into the building. She exhibits mood swings so frightful that Louise learns quickly to do whatever it takes to keep her new roommate happy. Lavinia comes across as a cross between Eloise at the Plaza and the Wicked Queen from Snow White, and until the book’s first plot twist, readers will probably have her pegged as the ‘creature’ of the book’s title.

But here Tara makes an intriguing move: before 150 pages have passed, Lavinia will be dead. This is hardly a spoiler; Tara telegraphs it, tells the reader explicitly in the first thirty pages. But it’s a seismic event for Louise, whom fate will force to step into Lavinia’s shoes, to somehow maintain the illusion that Lavinia is still alive – partly to keep herself from being implicated in her friend’s death, but also to keep up the new lifestyle she’s been clinging to.

The book’s press release calls it “a Ripley story for the Instagram age,” and Social Creature is certainly a top-tier thriller in the manner of Patricia Highsmith’s work. But I think I can trace a far longer line of ancestry. Tara confirms my suspicion. “I thought I wrote a book about God and sin and doubt and was kind of surprised to discover it was a thriller,” she tells me. “For me, this book was always about sin. Central to the book is the idea, from Dostoevsky’s Brothers Karamazov, that: ‘If God does not exist, everything is permitted.’ If the world Louise enters is ultimately one of illusion, where everything is permitted, she’s ultimately allowed to do and be whoever she likes – including Lavinia. Her journey was very much modelled on Raskolnikov’s in Crime and Punishment. In a sense the worst punishment for Louise is not being found out, because she has to contend with the hellish notion that there’s no order or justice in the world, no meaning. God hasn’t struck her down. She gets away with it.

“The book was very much written as a moral examination of the corrosive nature of sin, and the way in which Louise is in her own personal hell. Her ‘success’ imprisons her because the only thing worse than retribution is the idea that nobody’s watching over you at all.”

“I thought I wrote a book about God and sin and doubt and was kind of surprised to discover it was a thriller.”

But why stop at the Russian greats? If her mind is on God and sin, Dr Burton must surely be drawing on more primary sources. From the first page, we see Lavinia remake Louise into a carbon copy of herself, and the two begin to carry on in their Instagram posts as something more than BFFs – perhaps more like sisters. Here they are, two siblings: the favoured one and the envious outcast. I point out to Tara the distinct Cain-and-Abel vibe the two give off. “Oh, I totally agree,” she replies. “I’m so delighted someone picked up on it.”

But if such dark influences ought to shape Social Creature into something cold and bleak, there’s another side to the story. “I’m a religious Episcopalian Christian,” Tara is quick to point out, and so “a lot of the book was also about grace.” Along the way, both before and after Lavinia’s life is cut short, little cracks will form in her backstory, and Louise will begin to see a character with a lot more nuance – someone who, it turns out, might have had a lot more in common with her than she ever realised. Tara tells me: “I don’t think any of the characters in it are beyond redemption (and I think Louise’s realisation that Lavinia was a human person with good as well as terrible qualities is a major part of her sense of guilt later on). And I wanted to find an ending that didn’t suggest that the world really is fucked up and empty and meaningless, nor one that tied everything up in a too-neat bow.”

And if the cracks in Lavinia’s facade are telling, then something about the character of Louise sets off even more alarm bells. Tara captures Louise’s insecurities so convincingly, it can make the reader wonder if perhaps her portrayal isn’t coming out of whole cloth. Just look at the breathless excitement Tara is capable of conjuring, when Lavinia takes Louise into her social world for the first time at a Chelsea New Year’s party, and when the two of them, on Lavinia’s whim, throw themselves from a raised column onto the crowd:

So many people – they bear up her waist and thighs and back and Louise isn’t afraid; she knows, she knows they will not let her fall; she knows she can trust them, because they are all in this together and they are all so riotously, gloriously drunk and they all want her to stay up as much as she does, because it is a beautiful thing to be up so high, and they all want her to be a part of it.

And it gets better, later that night, as the two girls seal their friendship alone on the beach at Coney Island, stripping down and drunkenly shouting Tennyson’s ‘Ulysses’ at the waves:

Lavinia and Louise look at each other.

And they’re so goddamn cold Louise thinks they will turn into statues, they will turn to ice like Lot’s wife (or was that salt? she cannot think) and they will stay there forever, the two of them, hand to hand and breast to breast and foreheads touching and snow on their collarbones, and Louise thinks thank God, thank God, because, if they could petrify themselves for all time so that all time was nights like these and never any morning afters, then Louise would gladly give up every other dream she ever had.

I ask Tara if perhaps she has more in common with her protagonist than her social-media character lets on. “I guess that’s the trick of social media, right?” she replies. “I’m desperately insecure! I’m a deeply anxious person and spend hours agonising over whether, like, a waiter in a cafe likes me. But social media allows me to, for better or worse, reflect the best parts of myself (I’m reasonably good at the whole writing thing, so it’s a medium in which I can easily project my best self). I feel that ‘I project Lavinia but feel like Louise’ is probably quite common. I daresay Lavinia ‘projects Lavinia but feels like Louise.’ One of the things I wanted to capture in the book is precisely how similar the two women are. During an early phone call with my editor, I told her that if Lavinia had been born in Louise’s situation and vice versa, I think the exact same situation would have played out, plot-wise.”

But Louise isn’t just starry-eyed. There’s another dynamic going on, another voice in her head – one that sounds all too familiar to me. It’s the one that tells her, “There are two kinds of people in the world: the people you can fool into liking you, and the ones clever enough not to fall for it.” It’s the one that says, “we cannot be known and loved at the same time,” the one that is constantly reminding her that she used to be ugly and fat, the one that warns her: “You can’t fool them forever.” And you know what? Tara has that voice down.

I float a term I’ve heard other writers use to describe that voice: ‘impostor syndrome’. Judging from her earlier answers, I’m betting she has some idea of it, and can give me maybe one good anecdote about her experience with it. I step away from the computer for a few hours. Coming back, I see that she’s seen my message, but hasn’t replied yet. A couple of days pass and then, late one evening, I come back to my messages and see that bouncing ellipsis next to her avatar: “Tara Isabella is typing…” It’s late though, so I log out and go to bed, looking forward to what insight she might have for me come morning.

This is what awaits me the next day:

Two things

1. The very original draft of this book, from almost a decade ago, was inspired by a pretty quotidian in retrospect break-up: a teenage relationship that embodied many of the fantasies I had about myself as this naive person who nevertheless wanted to live a Bohemian Poetic Life.

(Let’s just say we read a lot of Tennyson in Trieste.)

Anyway, boring story, he ended up with my best friend, it doesn’t really matter now.

What mattered to me was this:

In my late teens and early twenties, feeling I had failed to be that person, this sort of grand poetic mysterious adventuress, I spent a lot of time and energy trying to become that person on my own, not through a romantic relationship.

So many of my early career decisions – from becoming a travel writer to going to chase hermits across the Caucasus or invade cults in Nashville or dressing like it was the 1930s, came from this intense hunger to prove myself worthy of the life and significance I wanted.

You can be cynical and say they were external things, but I think I had decided that I was going to Be That Person, damn it, and I was going to, I don’t know, make myself worthy of love by embracing this persona that, as a teenager, had always been a fantasy – like, I don’t know, if I was that person I’d magically be lucky in love and would never be hurt again.

(Spoiler alert: that didn’t happen.)

Anyway, that draft of the novel was terrible, but…

Second true fact:

This is the fourth novel I’ve had an agent send to publishers, and the ninth I’ve written since I was 13.

For most of my 20s this felt like a hugely shameful thing – that I had all these finished novels that were ALMOST good enough (i.e. good enough to get me an agent, but not good enough to get published).

And I walked around with an immense sense of shame and embarrassment about it, especially at literary parties.

But yeah, I failed massively. I have a metaphorical trunk containing three novels (plus five more that I never tried to get published), a book of short stories, and a whole lot of rejections! I just, you know, was less public about them.

But yeah, my current public persona is basically the result of having my heart broken a few really intense times and sort of doubling down on my own strangeness (which as often as not has been a source of ambiguous shame, too).

I think the persona I’ve created online is very much the person I want to be, and always wanted to be – someone who can take emotions and experiences and turn them into art.”

Here’s the thing:

I’m never going to succeed as, like, the kind of girl a lot of men want.

If I wanted to be that person (and there are a lot of times that I have actually wanted that), I genuinely could not do it.

I am a chronic oversharer, a messy drunk, I cry a LOT, I’m deeply neurotic.

When I like someone I tend to shut down and clam up and, I don’t know, attempt to intellectually best them so they think I’m smart or something.

I’ve had a pretty severe eating disorder most of my life.

I don’t think I even knew how to make friends until my mid-20s, because I was just this weepy oversharing over-emotional mess of a human being.

I think the persona I’ve created online is very much the person I want to be, and always wanted to be – someone who can take emotions and experiences and turn them into art.

And, sure, I dress weird. But I dress weird because I think it’s beautiful, but also because it makes me feel a sense of control over my own identity I don’t necessarily have.

I’m very conscious that financial privilege made it easier for me to do what I’ve done. But I think one of the great tragic ironies is that, no matter where we are and where we’re from, so many of us feel like Louise, in our own ways, and are terrified of failure (I certainly am!).

For me, a lot of that manifested itself in the conviction that I was unworthy of love, especially in some cases romantic love, because I was too much or too emotional or too weird or too intense, and my response was a kind of doubling-down.

Like: “You want intense? I’m going to give you intense. I’m going to go into the Caucasus with a lady hermit for a week!”

As Tara’s revelations flood my computer screen, they cast a sobering light on all those Instagram posts that have come before. And knee-deep in all these confessions, I realise that I need to unload a confession of my own, to myself at least: all this stuff I’ve been doing – grabbing a proof of her book, contacting her for an interview – I’ve been doing under false pretences. Of course I was going to love Social Creature; the first novel from a writer whose prose I so consistently admire was guaranteed to knock me out. But in some recess of my subconscious, this whole endeavour has been about me: all this congratulatory talk has been noise-making, a bid to drown out that voice in my head, that same voice that once told me “You fooled them,” but which ever since then has been piping up ever louder, asking me, paradoxically, “Why not you?”

Tara’s frank outpouring leaves me momentarily at a loss for words. In that moment I realise something: that voice in my head, it’s stopped its chatter too. As much as I’ve hated to admit it to myself, up until now I’ve envied Tara. I don’t envy her anymore.

It would be so easy, in the face of her revelations, to slide straight from envy to pity. Tara has already managed to make me pity Lavinia. I pitied Louise, even as I watched in horror at the decisions she was making. But Tara has no time for pity; she isn’t finished.

I’m hugely, hugely lucky that, between being university-funded for graduate school, and having a career as a travel writer that meant a lot of the expenses were paid for, I was able to make that [intense lifestyle] work.

Now, of course, I’m proud of the fact that I went, “Fuck it, I’ll start over” three times.

And I think my work has gotten so much better as a result.

I was able to create a life that I wanted, in part, because I had the privilege to do so, and (unlike Lavinia I hope) I’m intensely conscious of the moral implications of that. I feel that to waste any time – to write less, to work less hard – would be to cheapen the opportunities I’ve had.

Basically everything I’ve done in the last decade, and every effort I’ve made to create this identity I genuinely want and care about, has led to the creation of the good (I hope) manuscript you’re reading now.

Sorry, I hope some of that made sense.

It did.

Every word.

Lavinia doesn’t get a Third Act. Abel is denied even a line of dialogue. But for most of us, opportunities for redemption come up from time to time. Somewhere between that first terrible draft of Social Creature and today, Tara managed to seize such an opportunity, and claw her way to her state of grace.

After a long pause for thought, I send Tara a simple note of thanks. Clicking away from our Facebook conversation, I glance one more time at the little avatar next to her name on Instagram. She looks as dazzling as ever, that glitterati scribe whose dust I have imagined myself eating, whose charmed life I must confess to having envied for so long. And on impulse I find myself clicking on the image, navigating to her profile, watching the photo blow up to full size. The scene is all perfectly staged, in a gazebo on a country estate. She’s dressed in extravagant costume once more, giving us her profile while from outside the frame a companion holds a giant bottle of Prosecco to her lips. The accoutrements are as glamorous as ever, but I have to chuckle when the barcode on the side of the bottle catches my eye.

On another impulse, I click over to the taraisabellaburton.com home page. This shows our heroine seated in a plain old room, in simple black, looking straight back at us, a demure little smile on her face. A beaded necklace and matching earrings are her only bit of bling. She doesn’t need more; the sparkle before was intense, but the glow in this shot is the real thing.

Tara Isabella Burton is a writer of fiction and non-fiction. The winner of the Shiva Naipaul Award for Travel Writing, she has completed a Doctorate in Theology at the University of Oxford and is a prodigious travel writer, short story and scriptwriter and essayist. She works for Vox as their Faith and Religion Correspondent and divides her time between the Upper East Side of New York and Oxford. Social Creature is published by Raven Books and Doubleday in hardback, eBook and audio download.

Tara Isabella Burton is a writer of fiction and non-fiction. The winner of the Shiva Naipaul Award for Travel Writing, she has completed a Doctorate in Theology at the University of Oxford and is a prodigious travel writer, short story and scriptwriter and essayist. She works for Vox as their Faith and Religion Correspondent and divides her time between the Upper East Side of New York and Oxford. Social Creature is published by Raven Books and Doubleday in hardback, eBook and audio download.

Read more

taraisabellaburton.com

@taraisabellaburton1

Instagram: notorioustib

@NotoriousTIB

Author portrait © Rose Callahan

Brett Marie, also known as Mat Treiber, grew up in Montreal with an American father and a British mother and currently lives in Herefordshire. His short stories and other writing have appeared in publications including The New Plains Review, The Impressment Gang, PopMatters and Bookanista, where he is a contributing editor. He recently completed his first novel The Upsetter Blog.

Facebook: Brett Marie

@brettmarie1979