Petina Gappah: Trillion dollar questions

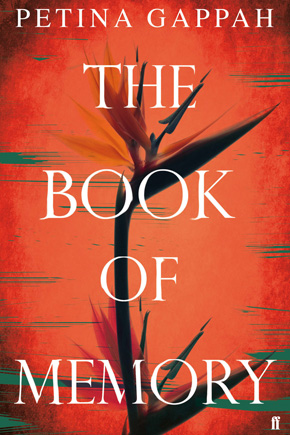

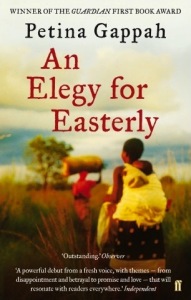

by Mark ReynoldsPetina Gappah’s dazzling debut story collection An Elegy for Easterly (2009) was shortlisted for the Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award and won the Guardian First Book Award. She tells me how the acclaim and attention surrounding her first book caused her to rethink the novel The Book of Memory, and reflects on her literary inspirations and hopes, and past and future changes in her native Zimbabwe.

MR: When the story collection came out in 2009, the novel was expected within a year or two. What held it up? And in what ways did the story and structure have to change before you were happy with it?

PG: Actually what happened is that the novel was the thing that my publishers were excited about, and my agent had this idea that the stories should come out first as sort of a place-holder. They were not meant to be the big event, and then they sort of became a biggish event, and that completely messed me up. I found myself really struggling, because now I had a book to write that had been sold on the basis of a few chapters. It sounds like every writer’s dream, and in many ways it’s a real First World problem, but it really was very difficult because then I was writing not into the void, as I had done with the stories, but into what felt like a weight of expectations. I found that very difficult to deal with, and that’s part of the reason why it took me such a long time to finish it.

Telling the story in a non-linear way allows you to withhold vital pieces of information, which are only revealed as Memory pieces her own story together. Were the writing of her notebooks and the mystery/thriller element part of your original intention?

Yes, absolutely. I was inspired by two books: Notes on a Scandal by Zoe Heller, which I absolutely loved, and also Ruth Rendell in her Barbara Vine guise, A Dark-Adapted Eye is one of my favourite novels. I wanted to write plot-driven literary fiction, and it was those two books that showed me how you can have a slow burn, or a slow reveal, where you withhold information and then everything makes sense by the end. So it was a very deliberate thing right from the start.

Those three years ended up being our way of reconnecting with Zimbabwe, and they thread into the novel… a lot of the passages I’m particularly proud of were directly inspired by things that I saw.”

Was your three-year return to Zimbabwe essentially a writing sabbatical; or was part of the intention to give your son a taste of growing up in the country?

It was both of those things. I wanted to take a break from working because I thought I needed to focus on the novel and other things as well, and then I also realised that my son had not really spent more than a month ever in Zimbabwe, and his Shona was slipping. It was really important to me as well that he get to know my family, especially my father who was quite frail. So it was a great opportunity for me to write, and to have Kush engage more with Zimbabwe and also for me to do some of the community things that I’ve always been interested in, like helping to rebuild the Harare City Library. So those three years ended up being our way of reconnecting with Zimbabwe, and they thread into the novel as well, because a lot of the passages I’m particularly proud of are passages that were directly inspired by things that I saw in Zimbabwe.

Like the lively dialogue, for example, which often flits between English and local languages?

Yes, absolutely. I eavesdrop quite badly, and I take notes copiously.

You have previously resisted the label ‘African writer’. What are the expectations it raises that trouble you?

You have previously resisted the label ‘African writer’. What are the expectations it raises that trouble you?

To be honest, I’m not as strongly resistant to the label as I was initially, because I realise that people will call you whatever they want to call you.

It started with your being dubbed ‘the voice of Zimbabwe’.

Exactly. I want very much to get away from this idea that I’m writing on behalf of Zimbabwe because I’m not, it’s a contested place. My take on Zimbabwe is not necessarily the next writer’s take on Zimbabwe. But when you are one of only three or four Zimbabwean writers who are published at a high level in the West, the temptation becomes, “Oh, she is the voice of this place”, and I was really struggling with that because in the first place it’s not true, and in the second place I don’t feel I’ve earned it. I might earn it one day, ten years, twenty years from now, but it has to be earned, and it has to be earned in the place you’re writing about, not in London or in Paris or wherever. So for me that whole notion of ‘African writer’ and ‘voice of Zimbabwe’ carries with it connotations of representing a place that maybe hasn’t asked you to represent it.

But inevitably there are some typically African tensions in the book between the traditions and superstitions of tribal people, and the colonial structures that have been imposed.

Well that’s largely what being a modern African nation is, because those superstitions and beliefs are not just superstitions and beliefs, they are a worldview. We had a traditional form of religion in which people understood that the ancestors determine your fate. So if you are unlucky, or if you are ill, you go to a diviner who tells you how you have offended the ancestors and what to do to remedy it. Then along comes Christianity to superimpose itself on this structure, but you can’t change the way people see the world overnight. So what we have in Zimbabwe is this sort of mishmash of the two traditions, and sometimes if Christian prayer doesn’t work to get you what you want, or if your cancer can’t be cured by a doctor, you go to the traditional route. So being a Zimbabwean is largely about balancing two different worldviews that are still equally valid and relevant to a lot of people.

A very funny moment that typifies that clash is based on a true episode, where government ministers are fooled by a mystic who claimed she could tap diesel from a rock. What was the outcome in real life, and what made you want to use that story?

It’s such a bizarre thing that you have a whole cabinet of ministers going to some rock in Chinhoyi to see diesel coming out! I mean, if it was petroleum coming out of a rock, or dark oil, black oil or whatever, you could sort of understand it because it’s a natural product. But diesel is a fractional distillate, it’s a man-made product, and if you see the pictures, it’s coming out of a pipe! I found it a really funny example of how Zimbabwe is misruled, because it just seemed to be the most ridiculous thing that anyone would want to believe that this was something that the ancestors had decreed would happen for Zimbabwe. It was a very comic episode in the litany of awful things that have happened. And you can’t always be talking about opposition supporters being beaten up, there are also these lighter moments that I think are just wonderfully revealing, and so the temptation for me was to see how I could work that story into this novel. What actually happened is the woman was arrested for fraud. Apparently she’d been given a farm, she’d been given something like thirty billion dollars when it meant something, and then she was arrested and exposed as a fraud, and she was in prison for a while, and now she’s back in Chinhoyi.

And the ministers were promptly sacked, or did they carry on?

I think they were promoted! No, they carried on, nobody’s ever sacked in Zimbabwe.

Setting a large part of the novel in Chikurubi prison allows you to explore relationships between the prisoners and their guards, and despite the harsh regime and filthy conditions, these are some of the warmest and funniest moments in the book. How much research went into capturing those conditions, and the tone of the conversations within those walls?

I made only one visit to Chikurubi prison, to drop off some books as I was also involved in a project to rebuild the prison library – I’ve got some great stories about that as well – but I didn’t actually go into the prison itself, because I would’ve had to sign the Official Secrets Act, and if I couldn’t write about it there was really no point in going, so I declined the opportunity. But when we went to drop off the books, I saw the most amazing sight. In the women’s section, prisoners were playing netball with the guards. Just a friendly game, they were taking it very seriously in a jokey kind of way, and I saw a kind of teamwork going on. Then I read this wonderful book called A Tragedy of Lives, which is a collection of prison stories, and one of the things that came out is the affection that a lot of the prisoners had for some of the guards. And then I thought, you know, it’s a human society like any other. You have the whole Stockholm syndrome thing going on, but here are some people who are just very human. And Zimbabwe is a Christian nation in many ways and motivated by Christian charity, so you have that as well. So it’s a very complex relationship, it’s not just about the oppressor and the oppressed.

So what is your favourite story about delivering books into the prison?

The superintendent said to us [she mimics the voice of a petty official] “You cannot have any books that promote homicide or any sort of crime. We don’t want any books about suicide, because we don’t want anybody to be depressed. And you can’t have any books about, you know, sex, homosexuals and so on. Romance is good, romance is very good – and children’s books.” So they only wanted romance and children’s books. But they’re also happy to have textbooks, because in the old prison system prior to the decade of crisis in Zim, you could actually complete your education in prison, and they’re trying to bring that back.

You’ve read all the Dan Brown books (and include a playful pastiche on your blog). Were you wary of stepping into Dan Brown territory by choosing an albino as your main character?

Do you know what, it only occurred to me later that Silas is an albino. But it’s kind of different being a white albino to being a black albino, because I think if you’re white then it’s not so obvious. I think mainly it’s the colour of your irises that mean you’re seen as different, but in terms of your skin, you could just be a really pale person. But it’s so funny you mention that. That’s actually one thing I have in common with Dan Brown. I do think Dan Brown has brought a lot of joy to a lot of people, so that can’t be a bad thing, right?

So why did you decide to make Memory a black albino?

Initially it started out as me trying to explore the notions of race and racial identity, and interrogating the meaning of whiteness in the context of Zimbabwe. I was interested in the idea that in Zimbabwe whiteness is seen as privilege, but there’s a kind of whiteness that is actually not privileged, and that’s the whiteness of living with albinism. And the albino girl became important as a visual sign of a curse that the family believed in. So for me it became more about that than the whole racial thing. After I’d started writing, it just became that if you believe that your family’s under a curse, and then you have a child who looks like that, you are definitely going to believe this is the curse that’s come back to haunt you.

The big shift in Memory’s life came when she was nine years old when she is seemingly bought and then raised by a white man named Lloyd, and a shift in your own circumstances came at the same age when Zimbabwe gained independence. So what are the parallels between your stories? You found yourself in a white-dominated school at that point.

Yes, I was one of the first six kids or so to integrate in an all-white government school, and by the time we finished primary school all the white kids had left, so those first two or three years were very strange. I have a strange accent for a Zimbabwean because it has had to shift. When I left my township school to go to this formerly all-white school, the kids mocked my accent because I sounded like a township kid, and after about five years at this school I moved to an all-black mission school in the rural areas, and everyone mocked my accent because I sounded Rhodie, so I worked very hard to change my accent. I think one thing I share with Memory at the age of nine is just feeling like an outsider. It’s a very lonely place to be as a child if there’s something different about you and everybody sees only that thing that is different. So I think that’s the one thing my nine-year-old self has in common with this character.

Memory says of those early years with Lloyd, “I was saved by books… I discovered books that became as necessary to me as breathing.”

That is the most autobiographical line in the novel!

Which books do you still cherish that you read at that kind of age?

It’s horribly embarrassing, but Ballet Shoes by Noel Streatfield was my favourite novel as a child because I had this dream of becoming a ballerina, even though I’d never taken a single dance step in my life. I loved all the ballet books, you know, Drina by Jean Estoril, I loved the Enid Blytons, I loved Malcolm Saville. What’s really interesting about the books we read as children is I think we belonged to the generation in England that is now in their 60s, because when Ian Smith declared independence for Rhodesia in 1965, sanctions were imposed, so the books that were in the country were the books from that era, and they were the books that we read. So I really thought I could go and hunt German spies on the Yorkshire Moors, that kind of thing. All these multi-culti, left-wingy books that became a big thing in Britain in the 70s, we just didn’t get to see any of those, and so it came as a shock to me as an adult to realise that Enid Blyton was not ‘quite quite’, and that golliwogs were racist, and all those class tensions with Mr Goon the policeman in ‘The Five Finder-Outers and Dog’ and so on were a complete mystery to me. Those were the books that we read, because that’s all we had, English authors of the 50s and 60s or before. And the classics, of course, you know, Treasure Island, and I loved King Solomon’s Mines. We read a lot of Rider Haggard for some reason.

How does the education system of today compare with your school experience?

One thing Zimbabweans have retained is the belief that education is the key to a solid future. It will always be there, I think, because it’s something that was ingrained into our minds because Rhodesia sort of bottlenecked education for black people. You had to be the best to get to the next stage. So we’ve always had this idea that it’s very competitive and you have to work really hard. But one thing that we’ve definitely lost out on is what I call the value addition that education can give you. I remember when I was a kid we’d go to a diary farm to see how it operated, we’d go to the tobacco auctions, we’d go to museums. We took a plane to Bulawayo on school trips. That kind of thing is just not being done anymore, except in private schools. I had a government education up to secondary school, and I find that primary schools are just not giving children those opportunities to see beyond their own worlds. There just aren’t enough of those experiences. For me that’s the thing that is missing the most. And to that I’d add books. Every child now has textbooks, they have four or five textbooks for comp, social sciences, English, Shona, maths, but that’s all they’re reading. The libraries just don’t exist anymore, or if they do they don’t have enough children’s books. I think that’s terribly sad for this generation of children, because for them education has become this incredibly narrow thing about getting the next grade.

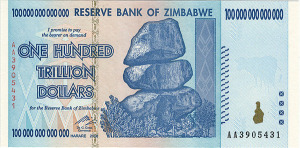

I spotted that as the Zimbabwean dollar is being phased out due to the economic collapse, the official exchange rate is 35 quadrillion [35,000,000,000,000,000] Zimbabwean dollars to 1 US dollar. What is the largest denomination Zimbabwean note you’ve seen, and will you be holding onto any currency as a keepsake?

I have some. I bought the trillion dollar ones on eBay. I think that’s the largest value that actually went into circulation. They’re being used to make different things now like boxes and wine bags, I’ve even seen earrings made of rolled-up dollar bills, that kind thing. I think it’s a very creative way of using the old Zim dollars, again testifying to the resilience of Zimbabweans, that they find a way to either make fun or to use them in a practical way.

Mugabe was universally acclaimed as the country’s saviour as Zimbabwe gained independence. How many still hold that view 35 years into his rule?

Mugabe was universally acclaimed as the country’s saviour as Zimbabwe gained independence. How many still hold that view 35 years into his rule?

I would say the people who voted for him. As I said, Zimbabwe is a contested place. I don’t like ZANU-PF. I like some of their policies, there are things I admire that they’ve done, but I don’t think ZANU-PF is good for Zimbabwe today. But that’s me, you know? According to the last election, the majority of people who voted think Mugabe is the answer. It is hard to know how free that election was, considering that there were no electoral reforms beforehand, but what is really beyond doubt is that a significant number of people really support the guy. I don’t know if it’s enough to give him the margin of victory that he enjoyed, but I know from family, from friends, that there are people who believe in him, and who believe in ZANU-PF.

How do you see the country shaping up once Mugabe finally leaves office?

One absolute certainty is that he won’t be president in 2025 – because his second five-year term will have run out! So unless they amend the constitution, definitely there will be a new president. Zimbabwe can only get better, I believe that very strongly, and it’s not just a Mugabe thing, it’s a generational thing. If you consider that the current vice-president, Mnangagwa, is about 70, and he’s a whole twenty years younger than Mugabe, what we need is for that generation, the Independence generation, to just go into retirement. In the next generation even in ZANU-PF there are some very competent people, they just haven’t been given the chance. And also what Mugabe leaving will do is cause a shift in the national imagination. There are so many people who have never known any other leader. I was born into Rhodesia, so I had Ian Smith, then Muzorewa before Mugabe took power, so at least I’ve known three leaders but so many know only him. It’s a shift that’s happened elsewhere – Mozambique, Zambia – just the idea that you can have different leaders of Africa. Since Mandela, South Africa has had four presidents, and that’s just since 1994.

What is the popular view of Grace Mugabe?

What is the popular view of Grace Mugabe?

She’s terrifying. Honestly, to me she’s the most terrifying person in Zimbabwe right now, because Mugabe, for all his sins, has a certain humility about him. He’s never claimed to be an absolute authority on everything, whereas Grace Mugabe is terrifying because she’s got a strange sort of entitlement, and she actually believes she can change scientific facts. I have an audio recording of her where she says that every single person in the world is born with HIV. It’s when you get sick that we say you’re HIV-positive, otherwise everybody’s HIV-negative. And it makes a twisted sort of sense to someone who hasn’t really thought it through, but she’s saying this to poor people, and speaking with authority because she’s the First Lady. To me there’s a kind of fantasist element to her that you don’t have with Mugabe at all. Mugabe has been on the wrong side of history for a while, for very concrete reasons, but Grace, I don’t think she even understands the concept of democracy. For example she owns a dairy, and she has an exclusive contract to supply the army. She’s the president’s wife! It wouldn’t happen anywhere else, the conflict of interest is so obvious. But not only does she have this contract, she actually talks about it as an achievement, in public! She’s a strange, strange woman.

In 2007, you translated Zviuya Zviri Mberi by Joyce Simango, the first novel to be written by a black woman in Rhodesia, from Shona into English. What has happened with the translation?

I did it for a friend as an academic project, and I want to see if I can publish it. It’s not a great translation, that was my first attempt to translate anything so it needs some work. But it’s such a lovely novel, about this young girl Tambu, how her mother rescues her children from their obsessive and abusive father, and the girl is the one that ends up uplifting the whole family.

More recently you’ve been involved in translating Orwell’s Animal Farm into Shona. How far is that progressed?

It’s done. For the next two weeks I’m proofreading it, and then we have to find a publisher. I don’t really want to self-publish; I’d love to have it published in Zim, but if not I’ve got a publisher in Nigeria who might publish it for the Zimbabwean market. It’s just been the most amazing project. Because Animal Farm, and 1984 as well to an extent, those novels are so Zimbabwean in their themes. You know, this idea of a revolution that has been toxified, that has been completely turned on its head. It’s not just Zimbabwean, it’s such a human story. I worked with a team of nine friends and each person did a chapter. I did the first chapter and set the tone, and then the others did a chapter, and now I’m going to revise and edit to make it consistent. It will be the first time Orwell has been published in an indigenous African language, so we’re very, very excited. And in fact, if everything goes to plan, we’re going to do a Ndebele version as well, and a Tonga version, which is another language in Zimbabwe that has long been neglected, and then I’ve got friends in Kenya and Tanzania who might do a Swahili version, so we’ll be reviving Orwell for young African readers, which will be wonderful.

And the Zimbabwe Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals is also involved.

Yes, all the proceeds from the Animal Farm book will go to the SPCA, because it’s a wonderful charity and they don’t really have a lot of support. As you can imagine, in Zimbabwe there are so many causes and so many people who need help and assistance, so to attract extra funding as an animal charity is really hard. I’ve got dogs in Zim, and I’ve worked a bit with animal charities, and of course there was the recent outrage about the killing of Cecil the lion. It’s a fine line, because on the one hand you don’t want to say animals are more important than humans, but at the same time animals are really important because they suffer from the kind of choices humans make that they have no role in.

So is 1984 next on the agenda?

1984 is a little too complex, I think. My next translation project is not Orwell at all, I’m going to do some of Somerset Maugham’s short stories. I’ve just finished ‘The Ant and the Grasshopper’, about a respectable man and his brother who’s a bit of a wastrel and is always on the cadge, a twist on the Aesop fable. I’m going to do maybe ten Maugham stories. They’re just so translatable.

Are your books on sale in Zimbabwe?

Yes, my Zimbabwean distributor has just ordered 250 copies of the novel from Faber, and then of course people bring them in as well from South Africa.

And what is the state of literature and publishing in the country?

It’s pretty healthy. We have two very good publishers, one in Harare, one in Bulawayo, and there’s a Shona publishing house as well in Harare. It’s great, considering the size of the market I’d say we have just enough publishing houses. What we don’t have is enough readers, and enough buyers of books. Except for what me and my friends call ‘Pavement Books’ – the boys who sell second-hand books on the street, which are very, very popular. So your Sidney Sheldons, your Jackie Collinses are selling at five dollars or whatever on the street. But for Zimbabwean authors and new books, the prices tend to be quite high because the publishers have to try and turn a profit. I was really horrified when the National Gallery sold my first book for US$35. I made a complaint and they brought the price down, but still it was twenty dollars, and that’s a lot of money.

Charles Mungoshi is the finest writer in Zimbabwe today. He’s published thirteen books – poetry, plays, short stories and novels. I think his work is too important not to be acknowledged outside Zimbabwe.”

Which other Zimbabwean writers should we be looking out for?

There are so many wonderful writers. There are some who’ve already reached the UK, like NoViolet Bulawayo, We Need New Names, Brian Chikwava, Harare North, Tendai Huchu, The Hairdresser of Harare and his new book The Maestro, the Magistrate and the Mathematician. And then you have of course Alexandra Fuller, Peter Godwin, Douglas Rogers. But the writers I wish people would get to know better are the ones who are still in Zimbabwe, who still haven’t really made it out to the world, and for me the biggest regret is that people don’t really know Charles Mungoshi, he’s I think the finest writer in Zimbabwe today. Unfortunately he’s not writing anymore, he’s recently suffered a stroke, but he’s of the generation of Dambudzo Marechera, who was like the wild child enfant terrible whereas Charles was more the stay-at-home type, he had a family, he had a proper job, he wore a tie every day, he didn’t have dreadlocks or anything like that, but he’s published thirteen books – poetry, plays, short stories and novels – he writes in Shona and in English and he’s just a wonderful writer. I think his work is too important not to be acknowledged outside Zimbabwe. Another I think is absolutely wonderful is Yvonne Vera, who unfortunately passed away a few years ago. She’s known by university students but not really by the greater public. Who else? There’s a poet called Togara Muzanenhamo who’s just absolutely wonderful, there’s a white guy from Bulawayo, in his 60s now, John Eppel, another poet, a really, really wonderful man. Bryony Rheam is published by a Welsh publisher [Parthian Books], she’s written a lovely historical novel called This September Sun. There’s so many; I could go on…

What’s next?

My next two books are almost done. One is a historical novel about the companions of the explorer David Livingstone – I can talk about it now because it’s almost done – and the other is a story collection called Rotten Row, and if everything goes according to plan it should come out next year, or early the year after. Rotten Row is the famous, now rather delapidated magistrates’ court in Zimbabwe, and all the stories are around the theme of crime.

Petina Gappah has law degrees from Cambridge, Graz University and the University of Zimbabwe and works as a counsel at the Advisory Centre on WTO Law in Geneva. An Elegy for Easterly and The Book of Memory are published by Faber & Faber. Read more.

Petina Gappah has law degrees from Cambridge, Graz University and the University of Zimbabwe and works as a counsel at the Advisory Centre on WTO Law in Geneva. An Elegy for Easterly and The Book of Memory are published by Faber & Faber. Read more.

theworldaccordingtogappah.com

Author portrait © Bathsheba Okwenje

Mark Reynolds is a freelance editor and writer, and a founding editor of Bookanista.

@bookanista