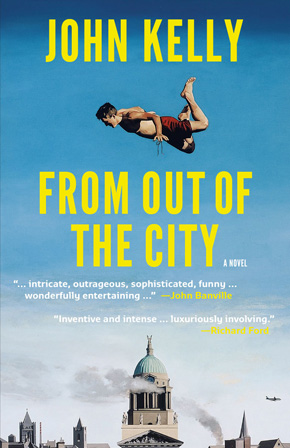

Portals of discovery

by John KellyFrom Out of the City is set in Dublin, Ireland some years from now. The President of the United States is assassinated during a state dinner and while the official account takes hold, an octogenarian named Monk discovers a version of his own, one which involves some people very close to home. This is the blockbuster element which lurks, often quite hidden, throughout – the part to use in the pitch for the movie deal. But what the book is actually about is dysfunction. Personal, social, civic, sexual, political, national, global and even cosmic – which is the part not to use in the pitch for the movie deal. From Out of the City was written at a time when our economy turned out to be utterly banjaxed and, for Irish people, it was emigration once again. Nothing was what it was supposed to be. Nothing was working. And as for the old reliables –well, the church was in a state of disgrace and our politicians had turned out to be gobshites after all. Here’s a list of things that helped it see the light.

1. ‘Chassis’

The word chassis, which appears in the best known line from Sean O’Casey’s Juno and the Paycock, is Captain Boyle’s personal pronunciation of the word chaos. It may also be a mispronunciation of crisis or, to increase the confusion, it may perhaps be little more than a makey-up word of the Captain’s own design. But whatever its root, chassis fitted well in a play set in the Dublin of the early 1920’s – a period when the whole world was in a terrible state of it – chassis that is. And as I began to write From Out of the City, a 21st-century chassis was thick in the Dublin air, replacing that more salubrious urban whiff of coffee, pastry and hops – that angels’ share that rises from venerable institutions like Bewley’s of Grafton Street or Guinness of St James’s Gate. My original working title was Everything is Broken – itself the title of a Dylan song of dysfunction. And also in the running was Chassis.

2. William Gibson

I shifted my story some years into the future in order to discombobulate both the reader and myself. I wanted to free myself from many of the obvious signifiers of Ireland’s present and, indeed, immediate past. The book was written in very particular times, after all – recession, crumbling institutions, the above gobshites, etc. And so what took my interest was a jaunt to the near future – where things have certainly changed but not to the point of sci-fi or fantasy. Dublin is still Dublin. It’s not Metropolis. No flying buses in the streets, etc. No robots. I like William Gibson’s speculative fiction. In fact Pattern Recognition is one of my favourite books and although it’s set in the present I think it may have been a very early spark for my book. I love the tone of the Gibson book, the rigour of it and the confident space it cleared for itself. And if it wasn’t a direct influence on the book, it was an influence on me.

3. Dublin

Dublin has been my home for the past seventeen years. I love this city and I hope I’ve managed to do it some justice in my book – although my near-future picture of it is certainly a grim one. But for all the decay in the novel, the richness of the city’s culture and history is still there and hence my narrator’s devotion to the naming of names and his constant references to public buildings and the names of streets. In a review of my book in the Irish Times, George O’Brien referred to “the estrangement of sign from signified” and I was pleased with that. Dublin to me is, and always has been, a place of history, romance and even glamour – in the same way that New York is, say, or Paris. It’s a thrill to know that Swift walked these streets, there’s a buzz in walking past the front door of Wilde or Yeats or Bram Stoker. And then, of course, we have Beckett and Joyce. The tracks of their backsides are still in the soft seats in many of my most beloved Dublin haunts, and when I read some of the greatest works of world literature I’m reading about places I know intimately. That’s powerful stuff.

Mainstream publishers seemed, to my mind, to have developed their own notion of what an Irish novel ought to smell like, and the reaction to my very early drafts only served to confirm my hunch. There were plenty of kind words of praise but no actual bites. I was disillusioned to say the least. But this is where the Norwegian writer Kjersti Skomsvold comes in. I read her debut novel The Faster I Walk The Smaller I Am and was very, very impressed – not just by the book itself but by the fact that someone had actually published it. It was a Beckettian affair after all, and ‘odd’ in a way which I found thrilling. And so, with my half a draft never expecting to ever find a home, I happened to meet Kjersti and her then publicist Jonathan Dykes. He then introduced me (and my book) to John O’Brien, the legendary editor at Dalkey Archive and now here we are. To be on the same imprint as Markson, Tavares, Puig and of course Flann O’Brien – well, that’s a result. And I was very honoured when Kjersti launched From Out of the City in Oslo in March.

5. Elvis Costello & The Roots

I’m not sure that music itself had any direct impact on the book, but that said, I love jazz and there’s a certain amount of improvisational soloing underway in From Out of the City. Now, whether that comes from listening to Sonny Rollins or reading Joyce, I can’t be sure. But that spirit is there. If From Out of the City were to have a soundtrack, though, I’d choose Elvis Costello and The Roots’ Wise Up Ghost. I was dwelling in that wonderful record throughout. It’s the music, as the Shangri-Las put it, of past, present and future.

6. White knuckles

Like so many Irish writers I was, years ago, hoovered up by a major English publisher. And yes, it all it seemed like a great idea at the time but, in truth, the experience was not a good one. It left me discouraged and adrift and it took me ten years to get back on any kind of track. And so it was important for me to reconnect with writers of my own and a slightly earlier vintage – people like Keith Ridgway and Mike McCormack, who seemed to be in the same boat as me. Actually, it turned out there were quite a lot of us and many of us are now finally back on the block. I was also seriously encouraged by the success of Kevin Barry who had broken through regardless. Kevin is a genius and a great guy too, and to see books such as his succeed – books not in the mainstream at all – well that gave me real boost. And despite the rejection so many of us have experienced, that fact is that many of us are still writing and finding ways to get the work out there.

7. The day job

Part of my day job involves interviewing writers and I cannot overestimate just how beneficial this has been to me as I make my own efforts. I’m in a very privileged position in that I can talk to people – uninterrupted – for a certain spell of time and that’s a very unique scenario. Uninterrupted is the thing. Reading closely, talking to the writers, extracting the wisdom – it all provokes the right energy for whenever I find the space to do my own thing. I have learned so much from people like Richard Ford, Paul Auster, Margaret Atwood and many more – just by asking questions and listening to the answers. An interview with someone like James Ellroy, say, can be an absolute masterclass for anyone interested. I’ll never forget him insisting on “reckless verisimilitude”.

Samuel Beckett by Edmund S. Valtman, 1969. Wikimedia Commons

8. Beckett

From Out of the City began with an account of someone getting out of bed. At that initial stage I was simply writing – there was no narrative and no notion of where it was all going. I just wrote page after page about a man getting up. I had been re-reading the Beckett novels and the spirit of Murphy was in that early experiment. It was only much later that I introduced the blockbustery plot – the assassination, etc. – albeit backgrounded in a rather perverse way. Beckett went to school in my hometown and he has always been a heroic figure to me. Everything about him – the work, the stance and, above all (or beneath all) the humour. He writes without fear.

9. Early mornings

For practical reasons I wrote most of the book very early in the morning. Yes, lying awake in bed thinking about things can be very useful and yes, there’s a certain half-awake state which can be quite revelatory, but the trick then is to actually get out of the bed and write. And being forced to write at five in the morning was a good thing, I think. My brain went off into places it might never have gone in broad daylight. So much so that I can’t recall writing this book at all, or even what I was thinking. And when I was done with the day job and the kids were all in bed I’d take look at what I had written before the day had even begun and I’d wonder what pre-dawn ghosts had taken possession of my keyboard. I highly recommend these early starts. Failing that, get a massive advance, quit work immediately, buy a cabin in the woods and work normal hours.

10. Ulysses

Irish writers sometimes talk about Ulysses in the same way students at Hogwarts talk about Lord Voldemort – the name must never be spoken aloud. Worse again there are those who insist that Ulysses is a book that nobody has ever read when, in fact, they’re speaking only for themselves. But if you have read Ulysses and enjoyed it, then to ignore its influence would be like a horn player ignoring the presence of John Coltrane, or a guitarist conveniently forgetting Hendrix. I’ve read Ulysses several times. I keep it by the bed. I read sections of it for pure pleasure. I laugh out and I marvel quietly. What I have produced is, of course, in the ha’penny place beside it. But has it influenced me? I sure hope so.

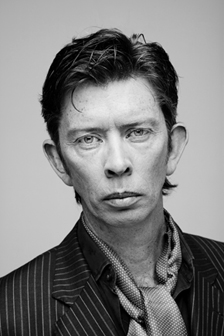

John Kelly has published several works of fiction including Grace Notes & Bad Thoughts and The Little Hammer. His short stories have appeared in various publications and his play The Pipes was broadcast on RTÉ Radio 1 in 2013. He lives in Dublin and works in music and arts broadcasting, hosting The Works on RTÉ1, and presenting The JK Ensemble on RTÉ lyric fm and Radio Clash on RTÉ 2fm. From Out of the City is published by Dalkey Archive Press.

John Kelly has published several works of fiction including Grace Notes & Bad Thoughts and The Little Hammer. His short stories have appeared in various publications and his play The Pipes was broadcast on RTÉ Radio 1 in 2013. He lives in Dublin and works in music and arts broadcasting, hosting The Works on RTÉ1, and presenting The JK Ensemble on RTÉ lyric fm and Radio Clash on RTÉ 2fm. From Out of the City is published by Dalkey Archive Press.

thisisjohnkelly.com