The portraitist

by Gaëlle Josse

“Combining real and fictional events, Gaëlle Josse has written a text as visceral as it is melancholy and vibrant.” Livres Hebdo

I have to admit that I had a few colleagues with whom I would have preferred never to have crossed paths. Sherman was one; the mere thought of him fills me with bitterness and disgust. Augustus Frederick Sherman. How could I possibly forget him? I can still picture him, stout and saturnine, with his prophet’s beard, round glasses, self-righteous expression, and prying eyes, constantly on the lookout. He was Chief Registry Clerk, in charge of the twenty men who dealt with the station’s correspondence; we devoured paper like ogres at Ellis Island. We worked closely together, and he had to report to me every day. I sensed a muted, simmering rivalry, even jealousy, towards me. He had a complex, I think, about his civilian status, subordinate to my commissioner’s livery. His personal ambition and pride could barely tolerate his position; I suspect he found it humiliating to be confined to doing thankless paperwork, unable to influence any concrete decisions to be made.

He ran his section along strict, even harsh lines, insisting that his men worked in complete silence, and he instituted a complicated ceremony, worthy of a Sultan, when it came to him being disturbed. Photography began as a hobby that became an obsession, and in later years it brought him a certain renown. He wore an aura of great importance when he went off to take pictures at the end of his working day. I didn’t have the authority to forbid him from taking his endless photographs of the immigrants being held at Ellis Island. My predecessor had tolerated, perhaps even encouraged it. When I became commissioner, I found myself with no say in the matter, for it was by then an established habit that was hard for me to challenge. And after all, what objection could I have made? His work wasn’t affected. His photographs brought him the recognition he had long dreamed of – how validated he felt when they appeared in National Geographic. You had to see his triumphant expression. I certainly wasn’t jealous of him. I just didn’t like the fellow, that’s all.

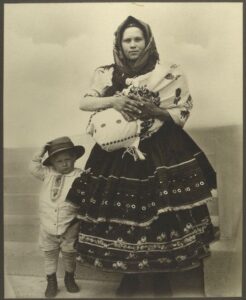

Sherman the photographer was frequently accompanied by his crony Luigi Chianese the interpreter, with his useful polyglot skills.* I hated seeing them together, they were like some sinister, silent force, a two-headed being both well-matched and ill-assorted, as they prowled the corridors during their after-dark expeditions. My authority had little hold over them, and I couldn’t quite put my finger on what it was they were brewing. If I consider the facts objectively, the two hundred or so photographs Sherman left are part of the memory of Ellis Island, testifying to the reality of the new arrivals and their fates. Families with innumerable children, standing stiffly in front of the lens in their best clothes, in a stunning demonstration of the breadth of our nation’s welcome. God bless America! Certainly, if we didn’t have them, what would we know of those millions of people who arrived here with fifty dollars in their pocket, speaking not a word of English, who slowly became assimilated into America’s soil, contributing to its glory and wealth? There was nothing in his project I could object to. But his photographs made me uncomfortable. I knew what was behind them, and I knew too well the way the two men worked, how intrusive and insistent they were. You had to see Sherman, as soon as he had tidied up his folders of mail and stacks of documents, how he would spend long hours peering into individual faces and considering groups of people. It seemed to me to be a form of harassment, a shameful pursuit.

Their faces were warped with fatigue, disfigured by anxiety and anticipation; entire families penned in by his lens, frightened children, exhausted mothers with babies in their arms.”

I know how determined he was once he had identified an individual, a couple, or a family. An ethnic type, as he used to put it. His potential models could not of course refuse to be photographed, as they had no idea whether or not it was required. He addressed those who were being held here for an indefinite period, either for medical reasons or for further interrogation. These were people in situations of complete insecurity, who faced the very real risk of being refused access through the golden door. Their faces were warped with fatigue, disfigured by anxiety and anticipation; entire families penned in by his lens, frightened children, exhausted mothers with babies in their arms, fathers watching over them all with benevolence and resolve. Many had never seen a camera before in their life.

Slovakian woman and her children by Augustus F. Sherman, c. 1906–1914. New York Public Library/Wikimedia Commons

I was told that often Sherman would rifle through their suitcases and trunks, looking for native costumes, elaborate headdresses, unusual jewelry, traditional tunics or boots, ornate belts, and other emblems of traditions and customs that were so different to ours. Perhaps I am badly placed to judge such practices and play the sensitive soul, but I certainly would not have been able to harass those wretched people, day after day, to dress up in their native attire. Sherman turned an unused room into a studio, in which he kept the large tripod camera that was necessary for the long exposures. There was a black or a white curtain for a backdrop, depending on the complexion and clothing of his subjects.

In an adjoining room, which was no more than a small closet, he set up a darkroom for developing his photographs. All I know of his background is that he was born in Pennsylvania, and that he and his family were members of the Episcopal Church. How he’d gotten here, I have no idea. But what I do know, and this is the main reason for my reservations about him, is that his anthropological portraits were published by journals promoting racialist propaganda. I don’t know whether or not this was with his consent, but I am sure it would not have been possible unless he himself had provided the images. These journals sought to use photography to demonstrate the disparities between races and the inferiority of some of them, using the pictures as a call for America to wake up, and for immigration from abroad to be limited. They campaigned for strict selection criteria for immigrants, and condemned entire ethnic groups for supposedly corrupting our country. This wrong-headed exploitation of racial types using an anthropometric approach horrified me.

I told him this during a meeting at which I rebuked him for allowing the publication of the portraits without having sought permission from the authorities at Ellis. These were, after all, professional documents, which could be considered confidential. He didn’t answer, and a heavy silence settled between us. I told him that it must not happen again, and stood up to signify that our meeting had come to an end. I didn’t look at him. A year later he retired, and a few months after that I learned of his death.

Sherman turned up with his tripod and his photographic plates. When I saw him, I was livid. I could not imagine how anyone could do such a thing. I stood blocking the entrance, my muscles coiled, ready to lunge at him.”

The difficulty of our relationship peaked during the drama concerning Nella. We came close to a fight, and I must say I would not have been sorry had I broken his jaw or smashed his skull, but he withdrew before I had the pleasure. During the wake for young Paolo, all the Italians were gathered in a room outside the main building that was reserved for this somber purpose, and lit only by candles placed around the body, which the women had tried to make presentable; everyone was dressed in black, standing around the coffin, reciting prayers and singing mournful hymns. Then Sherman turned up with his tripod and his photographic plates. I was standing at the back by the door, not knowing what else to do. When I saw him, I was livid. I could not imagine how anyone could do such a thing. I stood blocking the entrance, my muscles coiled, ready to lunge at him. Looking for something, are you, Mr. Sherman? He stopped, slightly out of breath with the weight of his equipment, and wiped his forehead with a large handkerchief. He revolted me. I knew I would have done something violent if I had surprised him a few minutes later already busy with his scavenging. I took a step forward. Beat it, right now! Don’t you dare think about trying to come inside. I’ll kill you if you try. From the frightened surprise I read on his face, I knew he wouldn’t take the risk. The Italians had noticed nothing through their tears and prayers, and Nella had no idea I was even there.

From The Last Days of Ellis Island (World Editions, £11.99)

* Author’s note:

Luigi Chianese, the Italian interpreter, did not exist, but I took some details of his career (though neither characteristics or actions, all of which are entirely fictitious) from that of Fiorello La Guardia (1882–1947), who worked as an interpreter at Ellis, before becoming a lawyer and then mayor of New York (1934–1945). One of the city’s airports is named after him.

August Sherman (1865–1925) was indeed employed at Ellis Island. He held the position of Chief Registry Clerk, and between 1905 and 1925 he took some two hundred and fifty photographs of newly arrived immigrants, many of which can be seen at the museum. Little is known about him and the details of his character and activities are my own invention. They reflect my shock as I stood in front of all these faces, captured at a moment that must have been for each one of them as much an ordeal as a new beginning. I stood and imagined the stories of all these people whose fates had been reduced to mere anthropological documents. The portraits were indeed published in journals for anti-immigration racial propaganda purposes, though the precise role played by Sherman in this process is unknown. Since then, the human and historical dimension of these portraits has been restored, rendering these women and men their dignity at last. It is the least that they are owed.

Gaëlle Josse holds degrees in law, journalism, and clinical psychology. Formerly a poet, she published her first novel, Les Heures silencieuses (‘The Quiet Hours’), in 2011. She went on to win several awards, including the Alain Fournier Award in 2013 for Nos vies désaccordées (‘Our Out-of-Tune Lives’). After spending a few years in New Caledonia, she returned to the Paris area, where she now works and lives. The French edition of The Last Days of Ellis Island received the European Union Prize for Literature and the Grand Livre du Mois Literary Prize. It is now published by World Editions in paperback and eBook, translated by Natasha Lehrer.

Gaëlle Josse holds degrees in law, journalism, and clinical psychology. Formerly a poet, she published her first novel, Les Heures silencieuses (‘The Quiet Hours’), in 2011. She went on to win several awards, including the Alain Fournier Award in 2013 for Nos vies désaccordées (‘Our Out-of-Tune Lives’). After spending a few years in New Caledonia, she returned to the Paris area, where she now works and lives. The French edition of The Last Days of Ellis Island received the European Union Prize for Literature and the Grand Livre du Mois Literary Prize. It is now published by World Editions in paperback and eBook, translated by Natasha Lehrer.

Read more

@WorldEdBooks

Author portrait © Héloïse Jouanard

Natasha Lehrer is a writer and literary translator based in France. She writes features and book reviews for newspapers including the Guardian, The Times Literary Supplement and the Observer. Her recent translations include A Call for Revolution by the Dalai Lama, Chinese Spies by Roger Faligot, Victor Segalen’s Journey to the Land of the Real, and Memories of Low Tide by Chantal Thomas. She won a Rockower Award for journalism in 2016, and in 2017 was awarded the Scott Moncrieff Translation Prize for her co-translation of Suite for Barbara Loden by Nathalie Léger.

natashalehrer.com

@NatashaLehrer