Dark, ingenious and daring: Pretty Ugly by Kirsty Gunn

by Wendy Erskine

THE WAY PEOPLE TALK ABOUT short stories often inclines to silversmithing analogies: burnished, finely wrought, beautifully crafted. That, or Fabergé eggs. And we say short story collection rather than group. Collection suggests careful selection from an array of available possibilities, white daisies on a vast lawn. In the afterword of Pretty Ugly, a collection of finely wrought, beautifully crafted stories, a character, Mary Masterson, comes home to find a bouquet waiting for her: ‘Great fatted chrysanthemums held by skinny stems jostled up next to double-headed tulips and phlox.’ Foliage poked out above the ‘greasy hearts of lilies.’ In the bouquet are also thistles and ‘other unkind-looking items.’ The assemblage reminds Mary of the event she just attended: the launch of a collection of short stories. The flowers prompt feelings of implacability, wretchedness, generosity, love. This metaphor for a short story collection – the bouquet – stresses variety and contrast. It emphasises how it is a gestalt, something more than the combination of its parts.

The launch attended by Mary Masterson was for the short story collection Pretty Ugly. In many ways, this is not a surprise, coming as it does at the end of a book which consistently emphasises the artifice of fiction. There is explicit consideration, within the stories, on ‘gateways to narrative’, the different ways where stories might begin, how horror stories might start with a particular kind of detail. A narrator makes the observation that there comes a point in all stories where the register of a narrative shifts, when a person is introduced who changes things, and this was ‘the moment.’ Reflexive commentary on its own fictionality is nothing new in writing. In lesser hands, it can seem like the twelve-year-old who has just seen The Matrix and feels obliged to tell us every hour that we are, in fact, living in the Matrix. But with Kirsty Gunn there is such commitment to investigating what makes stories, what’s included, how meaning is shaped, what’s left out, that such focus on the artifice of it all is ingenious and bracing.

Take ‘Dangerous Dog’, for example. The ebullient narrator, Kitty, who is attending creative writing classes, initially ponders how a dream could potentially be used in her story. She takes the time to consider both the pedagogy and credentials of Reed Garner, her writing tutor. He says you should never use cliches. ‘Do anything to avoid them, kids.’ We learn how the class is looking at the intersection between life writing and fiction, via Jane Eyre. What follows is our narrator’s highly schematic, patterned narrative involving the retelling of Jane Eyre; a gang of boys and a dog called Mr Rochester; ‘pulse moments’; and a final revelation that she married her tutor, expressed through Brontë intertextuality: ‘Reed… I married him.’ And yet this narrator, Gunn shows us, has missed where we might argue the more interesting story could be. When the narrator is telling the boys about the ‘red room’ of Jane Eyre, one of them, Steve, says quietly, ‘my gran used to put me in a room like that.’ Wow. But the narrator doesn’t pursue this. She’s too hipped on the Jane Eyre puns. Don’t trust the teller to tell the right tale, Gunn seems to suggest.

There is such commitment to investigating what makes stories, what’s included, how meaning is shaped, what’s left out, that such focus on the artifice of it all is ingenious and bracing.”

Storytelling comes under scrutiny too in ‘All Gone’, an account of a racist yummy mummy psychopath who opened fire in her daughter’s nursery. Her ‘story’ is told at a remove by a woman who visits her in jail, ostensibly to remind the killer that members of the church, ‘despite the magnitude of her crime, still love her, can forgive.’ Our narrator affects a kind of transparency: ‘this story, report or whatever… well, it’s not about me.’ And yet she is pretty high on her own supply of inside detail. ‘No one else would know that of course’, she says about her knowledge of where our killer stashed her weapons. ‘This was it’, the narrator says, ‘as I record it.’ And yet there is a disrupted chronology. In order to facilitate a big, money-shot ending, the narrator withholds until the last couple of sentences particular specifics about the killer’s actions which she has actually known about from the start. All things considered, this has been tawdry, bad-faith storytelling from our narrator, and sophisticated, daring storytelling from Gunn.

The stories in this collection have such range. Girlhood is handled in such a powerful way. Anna, a young child, doesn’t like to be touched: ‘people didn’t know, didn’t know, didn’t know. What it was like not to want to be touched. Ever. Ever.’ A bug she names Dreede, with a ‘funny little jumping body’, becomes a type of companion and projection of herself. She touches him with her ‘enormous finger’, an unwitting enactment of what she herself hates. ‘Don’t worry, my friend,’ she whispers. ‘I won’t do that terrible thing again.’ I found this so very moving. In ‘Transgression’ another girl, another outsider, finds solace in nature, although this time it is a more intensely animistic experience. An awkward girl, regarded as ugly, heavy and country by her ‘superior’ cousins, escapes from them into the bush.

‘Shhh,’ said the river. ‘Just listen.’

‘Use me,’ said the river bank, ‘and me,’ the bush whispered, ‘and me,’ the bush floor.

The afterword’s analogy of the bouquet of flowers conveys design and arrangement. In Pretty Ugly, artifice can be seen as necessary, even a delight. In ‘Praxis, or Why Joan Collins is Important’, two friends meet at a celebration of a book about historic rose gardens. This is nature ordered, labelled and named Whiskey Galore, Sunset, Faint Hearted and Skip-to-my-Lou. One of the friends is writing a biography of Joan Collins, another book to do with order and control. There is talk of Joan’s immaculate mask, ‘her use of wigs, props, costumes and make-up’; there is description of Joan as ‘living text.’ Joan herself declares that we’re just ‘one marvellous piece of show and tell after another.’ ‘Blood Knowledge’ is less playful. Venetia, the central character, is assured and privileged, her literary career successful. She has a beautiful garden. And yet, there is her ‘private, private life.’ Gunn writes that ‘Venetia knew, that the wife who each day applied fresh make-up to her face, drawing on, before the mirror, a fine dark pink or crimson lipstick mouth, also knew the very earth from which the garden was made held something secretive and so peculiar that it could spoil everything.’ These two stories make use of such similar elements – gardens, flowers, writing, masks, beauty, control – and yet a twist of the kaleidoscope produces such different, blithe and dark patterns. Blithe, dark, pretty, ugly.

Read an extract from ‘Blood Knowledge’

—

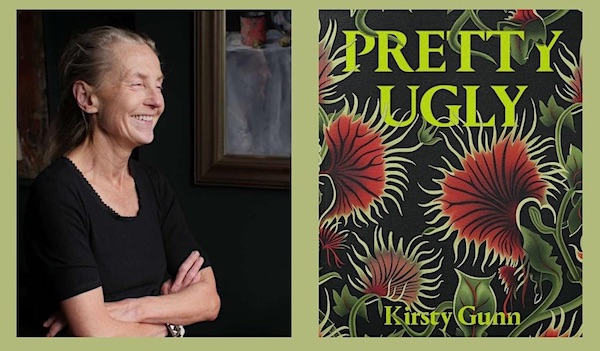

Pretty Ugly by Kirsty Gunn (left) is published by Rough Trade Books in paperback and eBook.

Read more

@RoughTradeBooks

Wendy Erskine is the author of the story collections Sweet Home (Stinging Fly/Picador) and Dance Move (Stinging Fly/Picador/The Tangerine Press). Her debut novel The Benefactors publishes in June 2025 (Sceptre).

@WednesdayErskin

—

Tuesday 21 January

Kirsty Gunn Book Event and Masterclass

6 to 8:30pm

The Highland Bookshop, 60 High Street, Fort William PH33 6AH

Kirsty Gunn discusses Pretty Ugly, and gives a masterclass on writing techniques. In the first half of the session, she will be in conversation with local writer Stephen Carruthers, as well as reading from her new book. For readers and writers who want to learn more, in the second half of the session, from 7 to 8pm, she will be hosting a creative writing masterclass focused on the short story. This is a rare opportunity in Lochaber to meet and learn from such a distinguished writer of both fiction and non-fiction: something to inspire for a dark January evening.

£12 admission includes a copy of Pretty Ugly and free entry to the masterclass (£5 event only)

More info and book