Pride, prejudice and parathas

by Soniah Kamal

“A delight from start finish.” Joshilyn Jackson

When I was fourteen years old, my Aunt Helen gave me my first Jane Austen novel, a beautiful red and gold hardback of Pride and Prejudice. I remember climbing onto my bed one summer afternoon in Lahore, the heat tempered by the roar of the AC, and settling down with this new read. It is a truth universally acknowledged that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife. Like most Austen lovers, I can recite this sentence at a moment’s notice, but at the time I stumbled over it. Something seemed off. Who had universally acknowledged this truth? Was it the ‘they’ I was always hearing about: if you dress like Madonna, what will they say? If you talk about unladylike things such as your period, what will they think? Don’t laugh like that, they’ll take offence.

As a Pakistani teenager, I was well acquainted with how they were capable of controlling my life. I was also well aware that single men, in possession of good fortunes, seemed less in want of a wife than their mothers seemed in want of daughters-in-law who fit a certain mould: voiceless, opinionless, thoughtless, long flowing preferably golden locks, alabaster complexions, and of course slim with nice breasts.

Puzzling over the sentence, I turned to the illustrations, here called ‘colour plates’. They were beautiful and the captions intriguing. The first was a woman in a sky-blue dress with white collar standing under a doorway with four people looking at her, two women and two men. The caption read: “She was shown into the breakfast-parlour, where her appearance created but a great deal of surprise.” Though I’d often visit the illustrations, it wasn’t until I turned sixteen and read Pride and Prejudice cover to cover that I found out why Elizabeth Bennet’s appearance was met with surprise. By then, as a literature student, I had figured out that the novel’s first sentence was ‘irony’ and that Austen was writing satire.

As soon as I turned the last page, I knew I wanted to retell this story of five sisters and their desperate-to-get-them-married-off mother who was so much like too many Pakistani mothers. I knew I had to retell this tale of a patriarchal culture that would have seen Lydia ruined and her family’s reputation tarnished by association, while Wickham gallivanted off with nary a scratch. In fact, do we not see versions of this scenario play out in our current time of #MeToo and Times Up?

As I read and reread all of Austen’s six completed novels, I noticed that while love stories certainly played a big part, her focus lay in the bonds of sisterhood and friendship.”

Jane Austen perfectly captures truths about human nature which transcend time and place, but also, for me, Pride and Prejudice was Pakistan. It was all here: the class issues and concerns over keeping up appearances, the worry over good girls keeping their good names intact in order to marry advantageously, the fear of scandal and downward mobility.

Additionally, as a child who came of age in a postcolonial country and was schooled in English and on British classics, I wanted to read fiction that reflected my everyday of chai, samosas and the colloquial mix of Urdu and English. There were, however, no such stories that I was aware of and so it had become second nature for me to mentally map a Pakistani atmosphere onto whatever I was reading. So scones became samosas, ginger beer became Pakola, and Enid Blyton’s fictitious boarding schools relocated to the Murree Hills. Thus my reading Pride and Prejudice and instantly wanting to turn it Pakistani.

As I eventually read and reread all of Austen’s six completed novels, I noticed that while love stories certainly played a big part, Austen glossed over proposals, and that wedding ceremonies were not even shown. Rather, her focus lay in the bonds of sisterhood and friendship. In Pride and Prejudice alone, Lydia again and again inadvertently tests the strength of her sisters’ love for her, while Elizabeth and Charlotte Lucas’s friendship is a test of opposites attracting each other.

Charlotte Lucas is not only the architect of her own marriage, but she defies her best friend’s disapproval in favour of doing what she believes best for her life. How can a friendship amongst women survive, or honesty thrive, if your best friend is disdainful of your husband? Unmarriagable explores this and more, as well as gender dynamics apropos of a Muslim Pakistan where traditionally the women and men do not mingle freely, schooling is segregated, and many women are not even allowed to meet their fiancés without chaperons.

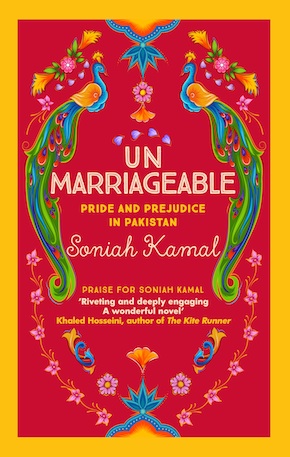

Over the years, as I attempted my faithful retelling, I kept returning to my red and gold hardback and the illustrations within and, with each look, that same initial spark would ignite and keep me going. There were so many false starts. I’d keep reworking because I was intimidated by the things I wanted to include and update: postcolonialism, beauty standards, feminism, status-obsessed societies, social classes divided through language and the place of English in Pakistan, as well as a dialogue between literatures of East and West and how the twain do meet. At least, they meet in Unmarriageable.

Soniah Kamal is an award-winning essayist and fiction writer whose debut novel An Isolated Incident was a finalist for the Townsend Prize for Fiction and the KLF French Fiction Prize. Her work has appeared in many publications including The New York Times, the Guardian and Buzzfeed. She was born in Pakistan, grew up in England and Saudi Arabia and currently resides in the US, where she teaches creative writing at the Etowah Valley Writers Institute, the low-residency MFA program at Reinhardt University. Unmarriageable: Pride & Prejudice in Pakistan is published in hardback by Allison & Busby.

Soniah Kamal is an award-winning essayist and fiction writer whose debut novel An Isolated Incident was a finalist for the Townsend Prize for Fiction and the KLF French Fiction Prize. Her work has appeared in many publications including The New York Times, the Guardian and Buzzfeed. She was born in Pakistan, grew up in England and Saudi Arabia and currently resides in the US, where she teaches creative writing at the Etowah Valley Writers Institute, the low-residency MFA program at Reinhardt University. Unmarriageable: Pride & Prejudice in Pakistan is published in hardback by Allison & Busby.

Read more

soniahkamal.com

@SoniahKamal