Wedding plans

by Soniah KamalMrs Binat’s ambitions for her daughters were fairly typical: groom them into marriageable material and wed them off to no less than princes and presidents. Before their fall, her husband had always assured her that, no matter what a mess Alys or any of the girls became, they would fare well because they were Binat girls. Indeed, stellar proposals for Jena and Alys had started to pour in as soon as they’d turned sixteen – scions of families with industrialist, business, and feudal backgrounds – but Mrs Binat, herself married at seventeen, hadn’t wanted to get her daughters married off so young, and also Alys refused to be a teenage bride. However, once their world turned upside down and they’d been banished to Dilipabad, the quality of proposals had shifted to Absurdities and Abroads.

Absurdities: men from humble middle-class backgrounds – restaurant managers, X-ray technicians, struggling professors and journalists, engineers and doctors posted in godforsaken locales, bumbling bureaucrats who didn’t know how to work the system. Absurdities could hardly offer a comfortable living, let alone a lavish one, and Mrs Binat had seen too many women, including her sister, melt from financial stress.

Abroads: middle-class men from foreign countries like America, England, Australia, Canada, et cetera, where the wife was no better than an unpaid multitasking menial, cooking, cleaning, driving, looking after children, and providing sex on demand with no salary or a single day off. An unpaid maid with benefits. Mrs Binat had seen enough of the vagaries of life to know that getting married to a middle-class Western Abroad could mean exhaustion and homesickness, and she would not allow her daughters a life of premature ageing and loneliness. As such, she was unwilling to marry them off to frogs and toads, because she was too good a mother to plunge her girls into marriage simply for the sake of marriage. For that, she would wait until Jena and Alys turned thirty-five. There was also the small complication of the girls’ reluctance to move abroad, since, for better or worse, they loved Pakistan. But, most important of all, if she sent her daughters abroad, she would miss them.

Of course, Mrs Binat knew through her own sad experience that even rich men could turn into poor nightmares. She would not allow her daughters to make this mistake.”

The plan was to remain in Pakistan and wed a Rich Man. Of course, Mrs Binat knew through her own sad experience that even rich men could turn into poor nightmares, for had she not married a Rich Man? And now where were her holidays, designer brands, and financial security? In her milieu, sons had been coveted for their income and thereby the security blanket they afforded retired parents, but, having married into wealth, she’d never cared to even pray for a son. Mr Binat too had stopped hoping for a boy after their fifth child was a girl. How she wished now she’d prayed for sons, and kept trying in order to spare herself the worry of a destitute old age. Being financially savvy and ambitious was a vital component of a successful man, and often Mrs Binat wondered whether she was to blame for not having had the upbringing to distinguish, in Barkat ‘Bark’ Binat, the real from the impostor.

She would not allow her daughters to make this mistake. She clutched the NadirFiede invitation. This was a real Rich Man fishing ground she was not going to waste.

‘We must give a marriage present that rivals everyone else’s. We must give thirty thousand rupees.’

‘Thirty thousand!’ Mr Binat glanced in alarm at Alys and Jena. ‘We are neither family nor close friends!’

‘Thirty thou is petty cash for Fiede Fecker.’ Alys laughed. ‘Five thousand from us should suffice.’

‘We don’t want to look like skinflints,’ Mrs Binat said. ‘They are sure to tell the whole town who gave them what.’

‘Mummy,’ Jena said gently, ‘five thousand rupees is stretching it for us as it is.’

Mrs Binat sighed. ‘Okay. Gifit is done.’

‘Gift,’ Lady said. ‘Gift.’

‘That’s what I’m saying. Gifit. Gifit.’ Mrs Binat shook her head. ‘Oof, I’m so sick of the tyranny of English and accent in this country. Alys, Jena, go get the trunk.’

Alys and Jena dragged in the metal trunk that housed the Binats’ sartorial finery, collected over the years – saris, ghararas, shararas, peshwas, lehengas, anarkalis, angrakhas, shalwar kurtas, thang pyjama kameezs. Most of the outfits had been tailored out of fabrics Mrs Binat had purchased in Jeddah, aware that with five daughters to dress, they would come in handy. Thankfully she’d had the foresight to pick neutral colours that could be worn through any turn of fashion and brightened with accessories and jewellery. The smell of mothballs rose as she riffled through the trunk, only to announce that Jena and Alys were definitely getting new clothes.

‘I want new clothes too,’ Lady wailed.

‘After Jena and Alys are married,’ Mrs Binat said firmly.

‘Oh, hurry up and get married already, you two!’ Lady said crossly. ‘And Alys, no one cares if you don’t want to get married.’

‘I’ve been praying so hard for them,’ Mari said, looking up from her nebuliser. ‘Obviously God must have good reason for putting us in this predicament.’

‘I’m leaning towards new silk saris.’ Mrs Binat looked Jena and Alys up and down. ‘The other guests can wear brand-name chamak-dhamak razzle-dazzle from head to foot, but you two will have an understated, classic Grace Kelly look.’

‘Everyone,’ Lady said, ‘knows people go classic when they can’t afford brands.’

‘People who depend on brands,’ Mrs Binat said resignedly, ‘have no style of their own.’

‘Silk saris are going to cost a lot, Mummy,’ Alys said as she tried to calculate exactly how much.

Ganju jee specialised in artificial jewellery that could rival the real thing. After she smiled at him a little too kindly, he’d always been excited to oblige with wares at excellent prices.”

‘Cost-effective in the long run. The money can come out of your father’s gardening budget’ – she ignored Mr Binat’s huge, shuddering sigh – ‘and we’ll spice up the saris with a visit to our special jeweller.’

Ganju jee specialised in artificial jewellery that could rival the real thing. He was located in Dilipabad’s central bazaar, in a pokey little alley where Mrs Binat had stumbled upon him. After she smiled at him a little too kindly, he’d always been excited to oblige with wares at excellent prices.

‘I want to wear a mohti.’ Lady grabbed the current issue of Social Lights and flipped past the pictures of people who seemed to do nothing but brunch, lunch, and attend fashion shows. She stopped at the fashion shoot where her favourite model, Shosha Darling, was wearing the garment of the moment: mohtis – miniskirt dhotis.

‘You can’t wear that.’ Mrs Binat peered at Shosha Darling’s bare legs. ‘It must cost a fortune. Look at all the hand embroidery on the border.’

‘I don’t have to buy it,’ Lady said. She turned the pages until she came to the weekly column ‘What Will People Say – Log Kya Kahenge.’ This week’s celebrity quotes concerned fashion designer Qazi of QaziKreations – Qazi had once designed an Oscar dress for a very minor celebrity, which had, back home in Pakistan, turned him into a very major celebrity – and Qazi’s latest creation, the mohti, for which he was taking orders.

Shosha Darling: I’m always given gifts!

Believe and you will receive.

‘That’s what I plan to do,’ Lady said. ‘Believe and I will receive.’ ‘Please, Lady!’ Alys said, laughing. ‘These stupid skirts are severely overpriced and Shosha Darling is an idiot.’

‘You think everyone is an idiot except for yourself.’ Lady scowled. ‘If I can’t wear a mohti, then I want saris with halter tops.’

‘You think everyone is an idiot except for yourself.’ Lady scowled. ‘If I can’t wear a mohti, then I want saris with halter tops.’

‘I wouldn’t wear a sari even if I was paid,’ Mari said. ‘Saris are for Hindus. As Muslims, our ties lie in Arab culture. We should be attending this wedding in burqas.’

‘I’d rather die,’ Lady said, ‘than go in a burqa to any wedding, let alone NadirFiede.’

‘Me too,’ Qitty said.

‘Mari, have you gone crazy?’ Alys said placidly, for after Mari’s dejection they were all quite cautious, and even Lady dared not bring up her poor grades or medical school. ‘Pakistani roots have nothing to do with Saudi burqa, or any Arab culture. Muslims have worn saris forever and Hindus have worn shalwar kameez.’

‘I despise it when you use that teacher’s tone at home,’ Mari said. ‘It’s that stupid club of yours, Mari,’ Lady said. ‘Each time you return with some holier-than-thou gem.’

‘Shut up, Lady,’ Mari said. ‘Alys, you know the club is just a bunch of us girls who want to discuss deen and dunya, religion and its place in our lives and the world. The last topic was menstruation, and we concluded it was probably a blessing for overworked women to be considered impure and so banished from cooking and other duties long enough to get a rest. We’re also starting good works, and the first good work is my idea.’ Mari beamed. ‘A food drive for Afghan refugees. After that we’re going to campaign for the abolishment of men selling brassieres and bangles and other purely female wares to women. It’s shameful the way the bra vendors openly assess our breasts and the bangle vendors hold our wrists as if to never let go.’

‘That’s truly admirable,’ Alys said. ‘And I think it’s time you also got an actual job. Come teach. Or look for an administrative position somewhere. We could do with the money, and you could do with getting out and meeting new people.’

‘We can certainly do with the money,’ Mrs Binat said. ‘Free kaa food drive! You’d better not take anything from the pantry without telling me. Good deeds! All this girl does is watch tennis all day long and wheeze whenever it suits her purpose.’

‘I swear, Mari,’ Lady said, ‘no one is going to marry you except a gross mullah with a beard coming down to his toes, and once he finds out what a party pooper you are, you’ll be the least favourite of his four wives.’”

Mari glowered. How she wished yet again that she’d got into medical school or that some pious man would marry her and take her away from her family. The first sister married. Then her mother would surely think the world of her.

‘Since we can’t afford brand names,’ Lady said, ‘the next best thing is to become as skeletal as possible. Hillima, can you make sure the cook prepares diet foods for me for the next two weeks before NadirFiede?’

Hillima, sitting by them and gawking at European models on the fashion channel, nodded.

‘I’m not going to NadirFiede.’ Qitty looked up from her sketchbook. ‘I’m sick of going to places surrounded by skinny girls fishing for compliments by complaining how fat they are.’

‘I’m not going either,’ Mari said. ‘I don’t approve of these ostentatious weddings, when Islam requires a simple ceremony.’

‘I swear, Mari,’ Lady said, ‘no one is going to marry you except a gross mullah with a beard coming down to his toes, and once he finds out what a party pooper you are, you’ll be the least favourite of his four wives.’

‘The only party worth worrying about,’ Mari said, ‘is the one after death, and if you don’t change your ways, Lady, you’re going to end up in hell.’

Mrs Binat slapped her forehead. ‘Mari and Qitty, you’re attending NadirFiede, whether you like it or not. Qitty, lose five pounds and you will feel much better.’

Qitty glared at her mother. She hadn’t had a single samosa so far, but now she popped one whole into her mouth.

‘See, Mummy!’ Lady said. ‘She doesn’t want to be thin.’

‘Shut up,’ Qitty said. ‘You’ve had six. Mari is right. You’re going to go to hell, Bathool.’

Lady had originally been named after Mr Binat’s mother, but after bullies at school rhymed ‘Bathool’ with ‘stool’, ‘cesspool’, ‘drool’, et cetera, Mrs Binat insisted Mr Binat allow her a legal name change. Bathool chose Lady, from the animated film Lady and the Tramp, even though her sisters cautioned against renaming herself after a cartoon dog, no matter how regal.

‘Sticks and stones may break my bones,’ Lady said to Qitty, ‘but names, hippo, will never hurt me.’

Mrs Binat half suppressed a smile.

Qitty was livid. ‘This is why she calls me names, Mummy. Because you favour her.’

‘God knows,’ Mrs Binat said, ‘I never play favourites. Qitty, I’m your friend, not your enemy, and I’m simply saying what is best for you. These days, you girls are expected to be the complete package. Gone are the days when a woman could get away with a single asset like a pair of fine eyes or a tiny waist. Now you have to be a bumshell.’

‘Bombshell,’ Mr Binat corrected her. ‘Bom, not bum.’

Mrs Binat flashed her eyes at her husband. ‘Please, Qitty, for my sake try to lose some weight before NadirFiede. No one wants to marry a fat girl.’

‘You wait, Mummy,’ Qitty said. ‘Bathool the Fool is going to do something so unforgivable one day that my being fat will be nothing in comparison. You should have seen the way she was making you-you eyes at the motorbike brigade outside of school today.’

‘Liar!’ Lady said. ‘Why should I make you-you eyes at motorbike boys? Although some are so handsome, while too many Rich Men are ugly.’

Mrs Binat squinted. ‘The uglier and darker the Rich Men, all the better for you, because they are actively hunting for fair and lovely girls to balance out their genes.’

‘Mummy,’ Lady said, ‘would you have married Daddy if he was ugly?’

‘Luckily for me,’ Mrs Binat said, ‘your father was handsome as well as rich. Alas, he was also unwise and so I became a tale of rags to riches, riches to rags. He let the corrupt Goga and Tinkle completely dupe him. Anyway, God is watching, and it is said the children will suffer for the sins of their parents.’

‘Pinkie, please.’ Mr Binat sat up. ‘How many times must I say, Goga’s and Tinkle’s children did nothing to us; leave them out of it.’

‘Daddy, calm down.’ Alys got up to kiss her father’s cheek. ‘Shall I get you fresh chai?’

‘Daddy’s chamchee, his toady,’ Mrs Binat said. ‘Run and get him a bucket of chai, so he can drown of shame in it.’

‘Hai, Mummy,’ Lady said, ‘how shameful it will be when we arrive at the events in our saddha hua Suzuki dabba. That car is so embarrassing.’

‘Can you please,’ Jena said, ‘be grateful for the fact that we at least have a car? Anyway, Lady, why would you want to marry someone who cares only about the make of your car or the size of your house?’

‘How is that any different from marrying someone because they are smart or nice?’ Lady said. ‘Criteria is criteria!’

‘How is that any different from marrying someone because they are smart or nice?’ Lady said. ‘Criteria is criteria!’

‘Too many people marry for the wrong reasons,’ Jena said. ‘They should be looking for kindness and intelligence.’

‘Jena, my sweet girl, you are too idealistic,’ Mrs Binat said. ‘On that note, Jena, Alys, if anyone asks your age, just change the subject. I so wish you’d stop telling everyone your real ages, but it is the fashion to think your mother unwise and never listen to her.’

‘But you’re always telling the girls to be fashionable,’ Mr Binat said, winking at Alys.

‘Wink at Alys!’ Mrs Binat threw a dagger of a look at her husband. ‘Please, Barkat, wink at her again. Keep teaching her to disrespect her mother. Keep teaching all your daughters to deride me. You used to do the same in front of Tinkle. That woman wished she had one per cent of my looks, and yet you allowed her and your brother to treat me like nothing. And what did they do in turn! They treated you like nothing.’

‘I’m going to the garden,’ Mr Binat said. ‘If I sit here any longer, I’ll have another heart attack.’

‘Please, go,’ Mrs Binat said to his retreating back. ‘One heart attack years ago and constantly we have to be on best behaviour. Who thinks of my health? I get palpitations at the thought of you five girls languishing in this house, never knowing the joy of marriage and offspring. Hai,’ she said, suddenly wistful, ‘can you imagine Tinkle’s face if even one of you manages to snag an eligible bachelor at NadirFiede, let alone all of you.’

‘Maybe Qitty can snag an eligible bachelor by sitting on him,’ Lady said.

Qitty picked up her sketchbook and whacked Lady in the arm.

‘Jena, Alys,’ Mrs Binat said, ‘shame on both of you if this wedding ends and you remain unmarried. Cast your nets wide, reel it in, grab it, grab it. But do not come across as too fast or forward, for a girl with a loose reputation is one step away from being damaged goods and ending up a spinster. Keep your distance without keeping your distance. Let him caress you without coming anywhere near you. Coo sweet somethings into his ears without opening your mouth. Before he even realises there is a trap, he will have proposed. Do you understand?’

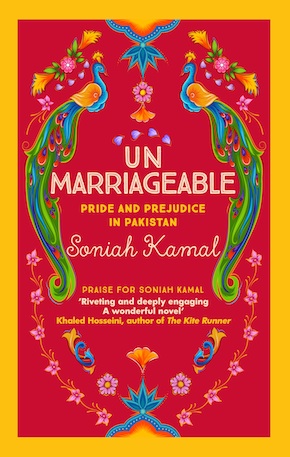

from Unmarriageable (Allison & Busby, £14.99)

Soniah Kamal is an award-winning essayist and fiction writer whose debut novel An Isolated Incident was a finalist for the Townsend Prize for Fiction and the KLF French Fiction Prize. Her work has appeared in many publications including The New York Times, the Guardian and Buzzfeed. She was born in Pakistan, grew up in England and Saudi Arabia and currently resides in the US, where she teaches creative writing at the Etowah Valley Writers Institute, the low-residency MFA program at Reinhardt University. Unmarriageable: Pride & Prejudice in Pakistan is published in hardback by Allison & Busby.

Soniah Kamal is an award-winning essayist and fiction writer whose debut novel An Isolated Incident was a finalist for the Townsend Prize for Fiction and the KLF French Fiction Prize. Her work has appeared in many publications including The New York Times, the Guardian and Buzzfeed. She was born in Pakistan, grew up in England and Saudi Arabia and currently resides in the US, where she teaches creative writing at the Etowah Valley Writers Institute, the low-residency MFA program at Reinhardt University. Unmarriageable: Pride & Prejudice in Pakistan is published in hardback by Allison & Busby.

Read more

soniahkamal.com

@SoniahKamal