Read in order to live

by Mika Provata-CarloneIT SEEMS THAT PEOPLE WHO SHOULD be experts on the subject of reading and of writing, perhaps also on the subject of children and the books that could open their minds, fashion their lives, vitally define their future, are of many minds as regards that very special unicorn of a genre, children’s books:

For C.S. Lewis, “A children’s story that can only be enjoyed by children is not a good children’s story in the slightest.” Gustave Flaubert, on the other hand, was more caustic, or perhaps cautious, given his own milieu and the experience of his time: “Do not read, as children do, to amuse yourself, or like the ambitious, for the purpose of instruction. No, read in order to live.”

It is perhaps James Baldwin who brings the two together, in his beautiful, poignant, all too human way: “You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read. It was books that taught me that the things that tormented me most were the very things that connected me with all the people who were alive, who had ever been alive.”

For Cornelia Funke, children’s books (all books that have anything of worth to say) are both the ultimate friends, and our quintessential selves: “Isn’t it odd how much fatter a book gets when you’ve read it several times?” Mo says in Inkspell. “As if something were left between the pages every time you read it. Feelings, thoughts, sounds, smells… and then, when you look at the book again many years later, you find yourself there, too, a slightly younger self, slightly different, as if the book had preserved you like a pressed flower… both strange and familiar.”

So “Read in order to live”, choose children’s books that you would read at any point in your life, reread them, if only to recover those “feelings, thoughts, sounds and smells” that made you all that you are, and remember, with John Locke, that “Reading furnishes the mind only with materials of knowledge; it is thinking that makes what we read ours.” Reflect with books, and consider in turn how children’s books reflect all that we have made of our world…

Click on cover images for more information,

or to buy from your favourite independent bookshop via Bookshop.org

First steps, wonders and tumbles…

Catch That Chicken! by Atinuke, illustrated by Angela Brooksbank

Catch That Chicken! by Atinuke, illustrated by Angela Brooksbank

Walker Books

Nigerian children (and adults for that matter) are amongst the most fortunate as far as stories and worlds of enchantment are concerned. Theirs is a living tradition of singing, dancing and mythmaking, with an extraordinary vernacular of deeply ingrained idioms and cycles of local lore. Ben Okri’s The Famished Road is in many ways almost just a transcription of that heartbeat and storytelling genetic code. Atinuke’s own tales are resplendent with the vibrant colours and patterns of her country, the majestic features of the people that inhabit it, the spirits, jujus, natural elements that infuse it with life and a certain eerie mysticism. As you chase that chicken, you will start wondering about whether a chicken is just that; about people and the world around them; about stories and why they matter, about how they connect us more than they divide us.

The Whales on the Bus by Katrina Charman, illustrated by Nick Sharratt

The Whales on the Bus by Katrina Charman, illustrated by Nick Sharratt

Bloomsbury Children’s Books

There used to be a joke favoured by a much older generation: “How many elephants can fit in a Mini?” In the original Morris Mini Minor, by Sir Alec Issigonis, that is…. The answer, which always took the unsuspecting by (often annoyed) surprise, was rather lateral: “Two in the front, and two in the back!” A similar reasoning applies to whales on buses, and this little book is a hilarious take on the limits of reason and the unlimitedness of human endearment and humour. Read, reread, read again…

No! Said Rabbit by Marjoke Henrichs

No! Said Rabbit by Marjoke Henrichs

Scallywag Press

For all of us, at some point or other in our lives (that point being, sometimes, of infinite dimensions…), No! may seem perhaps the only word worth uttering or living by. This is a book for the young Monsieur No or Mademoiselle No currently exercising that inalienable prerogative of growing up and individuation… It might lead them to that almost ineffable leap of faith that is only made possible by approximate phonetic association: that it is often better to seek to Know, than to simply say No.

The Cat and the Rat and the Hat by Em Lynas and Matt Hunt

The Cat and the Rat and the Hat by Em Lynas and Matt Hunt

Nosy Crow

Children relish both differences and similarities, the almostness and the perfect exactness of things. This is a book about perfect rhymes and near-perfect pairs, about the beauty of rhythm and the infinite possibilities of language, even at its most minimalist and laconic. Beat, tempo, dynamics and the sheer impetus and momentum of a language that communicates more than meets the eye will make this a favourite for those just discovering the incantational power of words.

Ernest the Elephant by Anthony Browne

Ernest the Elephant by Anthony Browne

Walker Books

Extravagant, flamboyant, exuberant, quirky, and yet full of wisdom and profound gentleness, this is a story about the greatness of kindness and the extraordinary powers of littleness. It will beguile you and inspire you in turns.

Just One of Those Days by Jill Murphy

Just One of Those Days by Jill Murphy

Macmillan Children’s Books

Enough said. You will have certainly had at least one of those by the time you are able to settle down to read this with your favourite young cherub by your side…

What Happened to You? by James Catchpole, illustrated by Karen George

What Happened to You? by James Catchpole, illustrated by Karen George

Faber & Faber

This is an absolutely extraordinary book, a quiet rebel of a book in fact, a gentle groundbreaker. How we ask questions, what questions matter, when to ask them, and whether sometimes not asking questions is in fact the best way to be caringly curious, are things that are at the heart of this real-life story about the visibility or invisibility of disabilities, and the way facts and perceptions can affect or confirm a life.

I Really, Really Need a Wee! by Karl Newson, illustrated by Duncan Beedie

I Really, Really Need a Wee! by Karl Newson, illustrated by Duncan Beedie

Little Tiger Press

You can even be philosophical about this delightfully rumbunctious story that will sound utterly and unvaguely familiar to all parents and to absolutely all children (and certainly to each and every ageing grandparent…) The question is an old, in fact a Promethean one: how do we learn to think ahead, and anticipate problems, situations and needs? We start, it seems, as Epimethean toddlers, with no forethought to speak of, and this beautifully piffling little book will bring all the thorny issues well out into the open!

The Goody by Lauren Child

The Goody by Lauren Child

Orchard Books

Kindness used to be a straightforward thing, before it came under the double strain of commodification and overcritical cultural analysis… Recover the heart and soul of what makes us human with this unabashedly clever, yet gently funny book, by an author who has come to know children and their quirks, their strengths and frailties like the back of her hand…

The Tindims of Rubbish Island by Sally Gardner, illustrated by Lydia Corry

The Tindims of Rubbish Island by Sally Gardner, illustrated by Lydia Corry

Zephyr

A mother and daughter spinning yarns sounds like a match made in fairytale heaven, and this book certainly proves the point. If you grew up with Mary Norton’s The Borrowers or BB’s The Little Grey Men, and if you are, like Pippi Longstocking, a “thing-finder”, then this is the first book in a series you’ll also want to share with a younger generation of readers, who dream small in order to envision the very greatest things.

The Little War Cat by Hiba Noor Khan, illustrated by Laura Chamberlain

The Little War Cat by Hiba Noor Khan, illustrated by Laura Chamberlain

Macmillan Children’s Books

How do you talk to children about war? About other children’s experience of war? This little cat will show you how, give you the words, set up the stage for thoughts and conversations that we should all be having right now.

How to Change the World by Rashmi Sirderhpande, illustrated by Annabel Tempest

How to Change the World by Rashmi Sirderhpande, illustrated by Annabel Tempest

Puffin

We seem to have an awful lot to say about everything that is wrong with our world. But perhaps we might also want to look at and think about all that is and has been good about the long journey of humankind. Fifteen stories to inspire a constructively rather than disparagingly critical perspective in those who will need to take the next crucial steps, write the new chapters of that ever-evolving, continuous human story.

Once Upon a Tune: Stories from the Orchestra by James Mayhew

Once Upon a Tune: Stories from the Orchestra by James Mayhew

Otter-Barry Books

Few have James Mayhew’s talents as a master storyteller. His books are infused with the most beguiling simplicity and the most extraordinary humanity, with the most exhilarating creativity. This anthology of stories about fairy tales and music are a mesmerising journey into art and beauty, into what adds meaning to each of our lives. Lavish and wise, gentle and powerful, a book to cherish, relish, keep.

The Boy Who Loved Math: The Improbable Life of Paul Erdos by Deborah Heilgman and Leuyen Pham

The Boy Who Loved Math: The Improbable Life of Paul Erdos by Deborah Heilgman and Leuyen Pham

Roaring Brook Press

This is an older book, yet it is worth tracking down a copy for those among your flock of imps or little angels with a particularly curious mind. A vivacious tale about an extraordinary and legendary life.

Journey to the Last River by The Unknown Adventurer (and Teddy Keen)

Journey to the Last River by The Unknown Adventurer (and Teddy Keen)

Frances Lincoln Children’s Books

This is quite possibly one of the most ravishing books you could come across this year. It is an adventure story, an unforgettable initiation into natural history, a journey of self-discovery, and even an unsolved mystery: who is The Unknown Adventurer, whose tin box full of notes and drawings was found stranded in the Amazon Forest by Teddy Keen some years ago? A map discovered in the Royal Geographical Society may lure you to hunt for clues, face the unknown, and especially treasure the world we presume to know, and yet whose marvels and wonders we often overlook and forget.

The Book Cat by Polly Faber, illustrated by Clara Vulliamy

The Book Cat by Polly Faber, illustrated by Clara Vulliamy

Faber & Faber

You may have perhaps heard of The Book of Practical Cats? And of its author, T.S. Eliot? This is the fictionalised story of a very real cat, Morgan, who ruled over the many floors of the publishing house Faber & Faber while Eliot was its editor in wartime London.

Halfway through a child-life’s journey…

Julia and the Shark by Kiran Millwood Hargrave and Tom de Freston

Julia and the Shark by Kiran Millwood Hargrave and Tom de Freston

Orion Children’s Books

Do you love numbers or words? Technology or nature? Power or friendship? Cities or the sea? Sharks or humans? Living for the moment or looking at landscapes? How do you hold up someone who is breaking down? Where does a daughter find the strength to understand a fragile mother? And how does a family survive strain or even a tragedy? This husband-and-wife story is a rite of passage as well as a bracing journey, full of questions, insights, above all an affirmation of relationships and families at their most vital and fundamental.

The Supreme Lie by Geraldine McCaughrean

The Supreme Lie by Geraldine McCaughrean

Usborne

Crisis politics and states in extremis are the stuff that some of the best yarns are made of, and Geraldine McCaughrean’s take on historical parable and social allegory will catch the eye and mind of a generation seeking to navigate past and present, just as the future looms both menacing and precarious.

The Edelweiss Pirates by Dirk Reinhardt, translated by Rachel Ward

The Edelweiss Pirates by Dirk Reinhardt, translated by Rachel Ward

Pushkin Children’s Books

Don’t be fooled by the quasi-Tyrolean title, this is quite a muscular tale of youthful fragility and indomitable resilience in the face of the most adverse – horrific – history. What do you do when the world around you goes mad? What can you do when you are only far too young? What are the stories that remain untold, yet keep haunting the generations to come? This is a riveting, highly dramatic, crucially human story about a group of young Germans fighting for their lives, struggling to stand up against the Nazis, with lives and, perhaps above all, consciences at stake.

When the World was Ours by Liz Kessler

When the World was Ours by Liz Kessler

Simon & Schuster Children’s

Have you read Manja by Anna Gmeyner (she was Eva Ibbotson’s mother, in case you are wondering…)? If you haven’t, add that book to your list now, read it, never forget it… If you have, then When the World was Ours is certain to resonate with you, become Manja’s companion, and a story you will want to think with and about. How do people who are joined together by friendship fall apart because of their different experience of a Zeitgeist? How do we develop a human and a historical conscience? How do we respond to history, to the vitiation of mankind? How do we stay ourselves in the midst of alienating chaos, in the throes of perverting sociohistorical forces? A poignant book, to not only read, but to reflect on, and especially to experience deeply.

The Puffin Keeper by Michael Morpurgo, illustrated by Benji Davies

The Puffin Keeper by Michael Morpurgo, illustrated by Benji Davies

Puffin

How do children’s stories get to become children’s books? This is one of the greatest stories in children’s book publishing, the story of Puffin Books and Allen Lane, as told by another master storyteller, Michael Morpurgo. If you were ever a Puffin Club member yourself (that is, a full-fledged Puffin), this is the book to give to new young eager readers, and who knows, they might themselves turn into new young eager publishers.

The Culture of Clothes by Giovanna Alessio, illustrated by Chaaya Prabhat

The Culture of Clothes by Giovanna Alessio, illustrated by Chaaya Prabhat

Templar Publishing

We have become global and multicultural, yet that has perhaps come at a grave cost, on certain levels: in the effort to join others, we sometimes forget how to be ourselves. This is a book that celebrates the will to see others for who they are, and to look in ourselves for everything we may be able to bring into that intercommunal conversation. A very strikingly illustrated book, a modern take on the invaluable tradition of books about the distinctiveness that makes each culture interesting, unique, a world to explore, preserve and admire.

Winnie-the-Pooh: Once There Was a Bear by Jane Riordan, illustrated by Mark Burgess

Winnie-the-Pooh: Once There Was a Bear by Jane Riordan, illustrated by Mark Burgess

Farshore

Where does a bear of very little brain fit in terms of readership? This will have to be up to you to figure out and decide. Jane Riordan has put together a collection of brand-new Pooh stories to revel in, to think with and dream about. You may be generous-minded enough to give this to someone very, very young… Or, on the other hand, you may feel that after all this hunting for books for children, yours or other people’s, you rather deserve a book all of your own. This may just be it. Whatever the size of your own brain.

Moominland Midwinter by Tove Jansson

Moominland Midwinter by Tove Jansson

Sort of Books

Originally published in 1957, but reissued in 1961 in an Italian edition with a brand-new set of additional colour illustrations and cover that are now aligned with the English text for the first time, this is a turning point in the life journey of the Moomins. A twinge of pain and a shadow of lingering darkness, a pinch of loneliness and bouts of anger or the steely grips of fear now enter the realm of these utterly mysterious, and yet inalienably familiar Finnish creatures. How does an imaginary world deal with adversity, uncertainty, or just plain Weltschmerz? The Moomins’ midwinter tale is perhaps one of the most resonant and poignant one of their saga, and arguably the one best suited to our current feelings, predilections and predicaments.

Marking time across the decades…

THE PAST TWO YEARS HAVE BEEN out of the ordinary, if not extraordinary, to say the least. What follows are anniversary-worthy books that marked young readers ten, twenty, thirty, forty, fifty or eighty years ago, a hundred years before today. Because we are what we read, and sometimes the quality of our world is very much reflected in the values and insights that may be derived from the fictional (?) written records of our humanity. When all is in doubt, it helps to look back and remember all that has sustained us in previous moments of happiness, crisis, disaster and reversal, or very deep sorrow.

Heart and Soul: The Story of America and African Americans by Kadir Nelson

Heart and Soul: The Story of America and African Americans by Kadir Nelson

Balzer & Bray/Harperteen, 2011

There was already a guide out of the wilderness we find ourselves in today, thanks to Kadir Nelson’s powerful account of history and its erasure, absence and irrefutable presence.

Room on the Broom by Julia Donaldson and Axel Scheffler

Room on the Broom by Julia Donaldson and Axel Scheffler

Macmillan Children’s Books, 2001; 20th Anniversary edition, 2021

It is fair to say that this book shook a fair amount of dust off many children’s bookshelves. The words Early Readers would never be the same following the arrival on the literary stage of Donaldson’s irresistibly redoubtable witch, her broom, her incantatory rhymes.

The Roman Mysteries: First Book, The Thieves of Ostia by Caroline Lawrence

The Roman Mysteries: First Book, The Thieves of Ostia by Caroline Lawrence

Hachette Children’s, 2001; Orion Children’s Books, 2002

Why do the Classics matter? Because they contain some of the most beguiling, shareable human stories in history. Because they embrace us, speak to us, can even translate our own stories today.

Sophie’s World by Jostein Gaarder, translated by Paulette Møller

Sophie’s World by Jostein Gaarder, translated by Paulette Møller

Aschehoug, Norway, 1991; Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1995; 20th anniversary edition, 2015

Because philosophy, the love of thinking, the love of reflecting in the company of others, living or long dead, about things that matter, will (hopefully) always be our world, as well as Sophie’s.

The Boys from St Petri by Bjarne Reuter, translated by Anthea Bell

The Boys from St Petri by Bjarne Reuter, translated by Anthea Bell

Gyldendal, Denmark, 1991; Puffin, 1994

A seminal story about children and WWII, about agency, and the power to change the course of history.

The Magnificent Nose and Other Marvels by Anne Fienberg and Kim Gamble

The Magnificent Nose and Other Marvels by Anne Fienberg and Kim Gamble

Allen & Unwin Children’s Books, 1991

The nose belongs to the unforgettable Ignatius Binz, yet each story has its own magnificence. In the tradition of the Brothers Grimm, Hans Christian Andersen and the vast realm of anonymous fairy tales, yet with a contemporary quirkiness and almost a perfect balance between reality and the world of sheer enchantment.

Goodnight Mister Tom by Michelle Magorian

Goodnight Mister Tom by Michelle Magorian

Kestrel, 1981; 40th anniversary edition Puffin, 2021

Stories are often the begetters of new tales, such is the extraordinary power of narratives, of the literary forms we give to our human experience. It is not difficult to see the genealogy behind Goodnight Mister Tom, with Oscar Wilde’s The Selfish Giant being perhaps one of its closest forefathers. The further poignancy of Magorian’s tale is staggering throughout, the dramatic pace relentless, the human resonance unignorable. A reminder that tragedy is almost always closer than we think, and that our potential for restorative goodness and for fortitude far greater than we sometimes acknowledge.

Ronja, the Robber’s Daughter by Astrid Lindgren

Ronja, the Robber’s Daughter by Astrid Lindgren

Rabén & Sjögren, Sweden, 1981; Methuen, 1983; OUP illustrated edition, 2018

Astrid Lindgren made her mark outside her homeland primarily thanks to the freckled feistiness of her Pippi Longstocking and the indomitable toddlerhood of Emil of Lönneberga. Yet her other characters also evince the very finest traits of their author: a talent for capturing the experience of childhood, for transforming it into lore and legend, or for perfectly framing it into irresistibly eccentric familiarity. Her depictions of the relationship between children and parents, between children and the greater, vaster world, remain reference points not only in terms of children’s literature, but also in terms of her readers’ own lives.

The Sword and the Circle by Rosemary Sutcliff

The Sword and the Circle by Rosemary Sutcliff

The Bodley Head, 1981; Penguin Random House Children’s, 2015

Rosemary Sutcliff may well be responsible, and to an incalculable extent, for several generations of budding historians or historiophiles. Her historical children’s novels invariably take both history and children very seriously, without compromising one jot either their beguilement or their intrepid sense of adventure. This is no exception, and stands more than well the test of time, just like Arthur and his Sword.

When Hitler Stole Pink Rabbit by Judith Kerr

When Hitler Stole Pink Rabbit by Judith Kerr

HarperCollins, 1971; 50th Anniversary edition, 2021

There should not be a single children’s bookshelf without this book. It captures the tragic irony of a child’s response to the horrors of WWII, as well as the sheer inability of children and adults alike to conceive that such horrors, madness and atrocities could ever be possible. Judith Kerr’s inimitable wry humour, which never mitigates either evil or tragedy, and her gentleness, which renders both physical and mental survival and reconstruction possible, her ability to invest each word, character and episode with innumerable layers of meaning, experience and empathy, have rightly made this a classic. Read it to someone young, and remember your own experience of the first time you came across that pinkish pesky rabbit.

1941 WAS A TURNING POINT, by any account, as well as being one of the most egregious junctures in the recent history of humankind. There was almost a boom of children’s books that year, perhaps for that very reason, some of which you can rediscover below.

Curious George by Hans and Margaret Rey

Curious George by Hans and Margaret Rey

Houghton Mifflin, 1941; Welbeck Publishing Group, 2018

Curious George started life in relative obscurity, as a minor character in a French story called Rafi et les 9 singes. The brainchild of two German Jewish writers, he would become one of the most beloved characters ever for children across the world. The human biography behind Master Curious Wandi George is as breathtaking (and heart-stopping) as the stories in which he stars: the Reys’ flight across Europe to the safety of the American continent and the United States, their Curious George manuscript clutched close to heart, embodies both the appalling predicament and the superhuman resilience of Jews and other suffering nations at the time. Remind yourself of this as your eyes flash across the pages trying to follow George along his insouciant flights of fancy, and think back on the year 1941 in which he properly made his entry on the storytelling stage…

My Friend Flicka by Mary O’Hara, illustrated by Tom Silbey

My Friend Flicka by Mary O’Hara, illustrated by Tom Silbey

J.B. Lippincropp Company, 1941; Ishi Press, 2020

Another landmark of a children’s book that was published just as the world was going up in flames. In the background of this almost quintessential American tale are stories and the history of the Great Depression, narratives of economic migration, and profound personal tragedy.

The Moffats by Eleanor Estes

The Moffats by Eleanor Estes

Harcourt Brace & World, 1941; Harcourt 60th anniversary edition, 2001

When things seem to be losing their clarity, and the world its balance, looking at times of comparable rockiness somehow steadies our gaze and our resolve to keep holding on. Eleanor Estes’ The Moffats are foil characters for many things, as well as meaningful protagonists of both drama and comedy in their own right. They conjure up a world where things were both simpler and more complex, where resources were far fewer, yet somehow more sustaining.

Fattypuffs and Thinifers by André Maurois, illustrated by Jean Marcel Adolphe Bruller

Fattypuffs and Thinifers by André Maurois, illustrated by Jean Marcel Adolphe Bruller

The Bodley Head, 1941; Vintage Children’s Classics, 2013

The English translation captures rather bewitchingly Maurois’ original Patapoufs et Filifers. Is this an allegory? Comical science fiction that seeks to foreshadow a viable future? There have been many readings of both the semantics of the characters as well as of the historical or other subtexts of the story, and you should try your hand at deciphering the riddles, and above all at relishing the tale’s fantastical exuberance. Remember, again, that André Maurois was Jewish, born Émile Salomon Wilhelm Herzog, that he once served as Churchill’s interpreter in WWI, that he translated with great feeling Kipling’s ‘If’, and that he fought with the Free French Forces in WWII. His Patapoufs et Filifers saw the light in 1930, and this too is something to keep in mind, as well as the choice to introduce the Fattypuffs and the Thinifers to an English audience in 1941.

The Black Stallion by Walter Farley

The Black Stallion by Walter Farley

Random House, 1941; 75th Anniversary edition, HarperCollins USA, 2016

Another book about humanity and its place in the world, about ineffable bonds between people and animals, but also between cultures, between centres and margins. The first of a series of stories with multilayered semantics and complex personal and historical references, this is a book that will make you think about strength and weakness, home and exile, belonging, individuation and connections, origins and new beginnings.

Little Town on the Prairie by Laura Ingalls Wilder

Little Town on the Prairie by Laura Ingalls Wilder

Harper & Brothers, 1941; HarperCollins, 2015

There are almost as many ways of reading Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House on the Prairie books as there are chapters in her fictional family’s saga. Perhaps the most incisive is to reflect on how we look at and whether we truly see things as they are – remember that blindness, notional and physical, is very much at the centre of Ingalls Wilder’s cosmos and metaphorical vernacular.

We Couldn’t Leave Dinah by Mary Treadgold

We Couldn’t Leave Dinah by Mary Treadgold

Jonathan Cape, 1941

Yet another horse or pony-themed book, this time the animal and human story explicitly addressing the historical moment at hand. Mary Treadgold apparently got tired of waiting for the right pony story to appear on those wartime children’s bookshelves, so she just simply wrote one she felt would be just right. An eerily premonitory tale, and a deeply engaging one. You will not want to leave Dinah behind once you have rested your gaze onto page one.

The Twins at St Clare’s by Enid Blyton

The Twins at St Clare’s by Enid Blyton

Methuen, 1941; 75th Anniversary edition Hachette Children’s, 2015

The Greeks knew well that in order to withstand and confront a dire tragedy, humankind needs the sustenance of judiciously calibrated comedy. For children staring at the looming darkness around them in 1941, Enid Blyton’s book may have been just that.

The Saturdays by Elizabeth Enright

The Saturdays by Elizabeth Enright

Farrar & Rinehart, 1941; Henry Holt, 2008

There was no war yet in New York in 1941, but there must have certainly been news and rumours of one somewhere not very far away. The Saturdays is both a riveting period piece of the city, and of childhood American style, as much as it is a remarkable document of historical and literary escapism. A revealing, and very moreish book.

American Indian Stories by Zitkala-Ša

American Indian Stories by Zitkala-Ša

Hayworth Publishing House, 1921; Dodo Press, 2008

Once again, the answer to all the questions about how we can ensure a polyphonic (as opposed to a uniform or monophonic) society were there already, for us only to retrieve, value, reflect upon, in this collection of mostly autobiographical stories by a seminal Sioux writer and activist. We seem, perhaps, to have been far more far-sighted, inclusive, curious and mutually empowering in our not too distant past, than we are willing to acknowledge right now?

HaJaBaRaLa by Sukumar Ray

HaJaBaRaLa by Sukumar Ray

U. Ray and Sons, 1921

This classic Bengali nonsense tale was written by the father of renowned filmmaker Satyajit Ray, and was inspired by Lewis Carroll’s Alice stories. Notable English translations include Jayinee Basu’s HJBRL (Nishtha, 2005), and Arunava Sinha’s Habber-Jabber-Law (Talking Cub/Speaking Tiger Publishing, 2020).

The Story of Mankind by Hendrik Willem van Loon

The Story of Mankind by Hendrik Willem van Loon

Boni & Liveright, 1921

At what was arguably another major watershed moment not only in terms of historic events, but especially as regards our very understanding of ourselves and our world, a Dutchman gave himself two mere months to ask that all important question: what is “the basis on which active membership to [human] history [may be] considered?” Membership does not constitute absolute or blind endorsement, although it requires (even prescribes) unflinchingly critical and deeply reflective inclusion. If you have changed the world, on a macro- or a microscopic level, then, van Loon asserts, you have been worthy of your existence. The extravagant criteria van Loom applied to his quest for a meaningful reflection of humankind’s journey through time speak of his own extraordinary ethos and vision: “Did the country or the person in question produce a new idea or perform an original act without which the history of the entire human race would have been different?” Remember the Latin etymology of extravagance: it is the story of outsiders and wanderers, as much as it is the history of those truly select few one may call outstanding and great. Many of van Loos’ own friends complained about the emphasis on the first part, for they felt an exclusive focus on the latter was what they would have rather approved of themselves: “They all wanted to know why, where and how I dared to omit their pet nation, their pet statesmen or even their most beloved criminal.” Read the original 1921 version of The Story of Mankind (further updated editions would follow after van Loos’ death in 1944, yet few matched his clarity, luminous curiosity, or human engagement), and you will realise that we have been, in our motley past, far more expansive, rather than expansionist in our perception of the world, than we may wish perhaps to remember.

Read in full at Internet Archive/New York Public Library

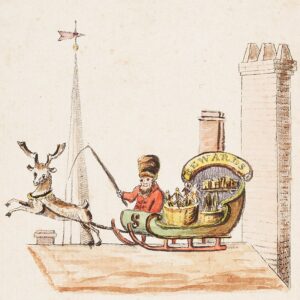

Illustration to verse 1 of ‘Old Santeclaus with Much Delight’. Beinecke Digital Collections, Yale/Wikimedia Commons

GOING BACK ANOTHER CENTURY STILL, 1821 was the year of ‘Old Santeclaus with Much Delight’, an anonymous, highly didactic poem that appeared in The Children’s Friend: A New Year’s Present to the Little Ones from Five to Twelve. It featured the very first illustrations of the story of Santa Claus (cum reindeer and red robes) ever published.

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.

bookanista.com/author/mika/

Support your favourite independent bookshop by buying books for giving (and keeping for yourself) at Bookshop.org