The reluctant romantic

by Thea LimI didn’t set out to write a love story. In fact, I was startled when my agents Karolina Sutton and Lucy Morris chose to position my book as a love story. I said, are you sure it isn’t migrant literature disguised as time travel? Or a disquisition on the passage of time, wrapped in a mystery? But they pointed out it was the love story held all these elements together. I had tricked myself into writing a romance.

In the same way that it wasn’t obvious to me I’d written a love story, the romance between Polly and Frank – which takes place in a past timeline that’s woven with the present – was most difficult for me to write. One reason is this: I’m a filthy romantic, and I’m regularly overcompensating for this, trying to keep my sappy vibes in the closet. (Spoiler: they escaped.)

Another reason the courtship was challenging to write: my romantic hero, Polly, is a little emotionally closed-off. She has to be, in order to convince herself to travel one-way into the future. You need a vice-grip on your emotions to pull off a feat like that. I’m drawn to such characters, tank-like champions who just get it done, like my mother and her mother. Plus, it was interesting to write about someone like that in love, telling a story for those of us who didn’t dream of our wedding day, who dreamed instead of a sturdy partnership, or even just a happy life, whatever it may contain. Still, it was tricky. I had to accept that some readers just weren’t going to buy in, if the hero wasn’t given to wild flights of passion.

What is both magical and impossible about textual narratives – as opposed to visual ones like film or TV – is that the words are all we have. And if it’s not said (either in or between the lines) the reader can’t follow.”

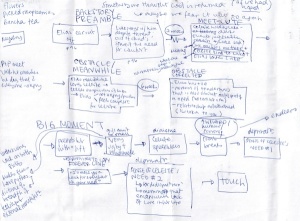

Faced with all this, I searched out models, especially unconventional love stories. I obsessed over Edward P. Jones’ The Known World, which is not a love story at all, but contains one of the most moving and illuminating scenes of people falling in love I’ve ever read, when Elias and Celeste find each other in the most abject conditions. I mapped it and then shamelessly used it as a template for my own characters’ meet-cute. My final version of that scene turned out vastly different, but Jones’ work got me started (see flowchart above – click to enlarge).

“A devastating debut.” Toronto Star

I searched for narratives where much is said with very little. I wanted to match the way I told the story, with who Polly is. My writing teacher, Mat Johnson, gives lectures on the way Children of Men uses a single prop: a ping pong ball. The ball abbreviates years of history into thirty seconds of film, showing that no matter how Julian tries, no one but Theo can catch the ball when she throws it (metaphor alert). The flashbacks in Brokeback Mountain are similar; they are so fast – like when Ennis hums a song from childhood for Jack – and it’s the restraint in the storytelling that says so much about how unbearably fleeting love can be. Inspired by these innovative examples, I worked to put my reader on a ‘need to know’ basis.

But I hit a problem. This preference for compression, paired with my reluctance to let loose my inner Diana Gabaldon, had made the love story too subtle. So much of what love is, is unsaid. I didn’t want to have to spell out what was between Polly and Frank; that felt counter to the nature of love. Yet what is both magical and impossible about textual narratives – as opposed to visual ones like film or TV – is that the words are all we have. And if it’s not said (either in or between the lines) the reader can’t follow. What a predicament.

Then I hit the jackpot. I met Cassie Browne at Quercus, who could see the story before it was there: its shadow. Over several months, along with my Canadian editor Helen Smith, she helped me fill it in, from small but vital changes (like turning up sentences that whispered about love) to big changes. The original submission I’d sent my agents has five flashback chapters; the final version of my novel has eight.

While I didn’t intend to write a love story, I did intend to write a story about how we love, even though we know everyone will eventually go away from us, through life or time.”

I made one final change. One of the questions An Ocean of Minutes poses is whether or not it truly is better to have loved and lost than to have never loved at all. I believe the writer’s job is not to tell us how to be, but to show us many ways to be, fully rendered, so we can choose for ourselves. But my US editor Tara Parsons pushed me to provide an answer to the question I’d posed. You’ve put the reader through the ringer, she said, you can’t leave them hanging!

While I didn’t intend to write a love story, I did intend to write a story about how we love, even though we know everyone will eventually go away from us, through life or time. I wanted to show this loving act in motion, without making an argument as to its value. But when I truly considered it, I did not want to push a book into the world that said it was possible there’s no point to connection, or no point to love.

So I wrote an answer. I added in a paragraph, right before the final one: “She thought all those days had been lost, like beams of light at the end of their reach, scattering into darkness. But he had kept them safe after all.” And then the book was done.

Author portrait © Elisha Lim

Thea Lim‘s writing has been published by the Southampton Review, the Guardian, Salon, the Millions, Bitch Magazine, Utne Reader and others, and she has received multiple awards and fellowships for her work, including artists’ grants from the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council. She holds an MFA from the University of Houston and she previously served as nonfiction editor at Gulf Coast. She grew up in Singapore and lives in Toronto, where she is a professor of creative writing.

An Ocean of Minutes is published by Quercus in hardback, eBook and audio download.

Read more

thealim.org

@thea_lim