A remarkable woman

by West Camel

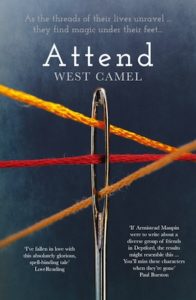

“Delicate, evocative prose telling an intriguing story with contemporary relevance, insight and compassion.” Live and Deadly

As I made the final corrections to the proofs of my debut novel Attend, I was asked by my publisher whether I wanted to include a dedication. Having toyed with some names – a few people in my life I thought might fit the bill, the idea came to me that I should dedicate this novel to someone I didn’t know, and have never met: Deborah Wybrow, the woman whose story sowed the seed of the novel in my mind.

In 1835, the London and Greenwich Railway – the first railway in London – was due to open its first section: between Spa Road, Bermondsey and Deptford. A local Deptford woman was to be its first passenger. Her name was Deborah Wybrow. She was a seamstress, or a knitter (depending on your source). More importantly, she was 102 years old – her age the reason she was chosen for the first-passenger role. But the honour was never fulfilled. Before the inaugural trip, Deborah died after a fall down the stairs of her house in Crossfield Lane (now Street), in which she ‘dislocated her neck’.

These details are all I have ever been able to discover about this woman, but when I first read them in a book of local history (I was living in Deptford at the time), they seemed not only to form the bones of a story, but also to beg a range of questions that laid the foundations for a new and very different tale.

How did this working-class woman reach such a great age – an achievement even in our own times? Was her longevity so extraordinary that her low societal position was winked at, and she was chosen as the railway’s first passenger over some more prominent person? Did someone object to a lowly woman taking a high-profile role? Was the fall truly an accident?

It was here that the creative spark flared in my mind. And in one of those flashes of inspiration that seem to come from nowhere, but every writer knows comes from some deep, atavistic source, I asked myself another question: what if Deborah’s death hadn’t occurred at all? She existed in this miniature sketch in a local-history book. Might she still exist in the flesh?

Thus I began the work of writing a novel – a work set in contemporary Deptford but with a woman born in the 18th century at its heart. I soon ran into problems, however. The contemporary elements – the new characters I’d introduced to interact with this 300-year-old – were relatively easy to write. I’d met these people. I’d walked their streets. The leap of imagination required to fictionalise the world around me wasn’t so great. But I found it difficult – almost impossible – to approach the character who was the core of the book. The manuscript drifted. The pages piled up, but there was something aimless about what they contained.

Deborah being 300 years old was not a problem, my fellow workshop writers said, but I needed to be sure that she was authentic. How would I address her use of language? What would her body be like after three centuries?”

The problem I faced was solved in the most practical of ways: I enrolled on an MA creative writing course. While the ‘study’ of creative writing is often maligned, for me it unlocked the possibilities and problems my unwritten novel was presenting. And it did this in two ways: through the workshop process; and through exposure to literary theory.

Deborah being 300 years old was not a problem, my fellow workshop writers said, but I needed to be sure that she was authentic. How would I address her use of language? What would her body be like after three centuries? Her teeth would be black, one insisted. And what experience and knowledge would she have brought with her over all these centuries? Without intending or wanting to I had strayed onto historical fiction territory, with all its challenges and demands. And by adding in an element of magical realism, I had complicated my novel even further. It seemed like I had created an enormous task for myself.

The course, however, also introduced me to the work of literary structuralist Tzvetan Todorov – and specifically his concept of the ‘fantastic’ literary form. To define the fantastic Todorov draws on two other forms: the ‘uncanny’ and the ‘marvellous’.

In the uncanny, apparently supernatural events have a natural explanation. Freud offers a personal experience of the phenomenon in his essay ‘The Uncanny’: wandering an unknown city, he leaves a square, thinking he’s walking in a straight line. But he finds himself re-entering the same square he left. That unnerving moment in which he’s unsure what has happened, resolved by the realisation that he’s somehow lost his way, represents the uncanny.

The marvellous is an even simpler form to describe. Do you believe in fairies? If you do, Tinkerbell lives. The marvellous is the acceptance of the supernatural – at least within the universe of the text in question.

The fantastic, according to Todorov, is defined by hesitation. The reader, and importantly the character(s) populating a particular text, hesitate between the uncanny and the marvellous – between natural and supernatural explanations for the strange, apparently supernatural events they witness.

A 100-year-old Deborah living in contemporary Deptford would be born around the same time as my own grandfather. She would have experienced the penury and hardships of mid-20th century London, as my grandparents did.”

I realised immediately that Deborah as a 300-year-old immortal put my novel firmly in marvellous territory. The uncanny was not an option – there is as yet no natural explanation for such longevity. But what of the fantastic? What of that delicious moment of hesitation and doubt that ends some works of fiction? Todorov’s key example of the fantastic form is Henry James’ novella The Turn of the Screw. Was there a way I could create the kind of quartz-crystal perpetual oscillation that continues long after you’ve turned the last page of James’ story?

I realised I could – and do so in a way that solved my Deborah problem.

The Deborah Wybrow I’d been writing was a fictionalised extension of the original, real-life Deborah Wybrow, who died in 1835. I could create a new Deborah Wybrow, one who was still old, but whose great age the laws of nature wouldn’t refuse. What’s more, a 100-year-old Deborah living in contemporary Deptford would be born around the same time as my own grandfather. She would have experienced the penury and hardships of mid-20th century London, as my grandparents did.

But while her life might be an ordinary one, might it not be extraordinary too? Might the supernatural intervention that made my original conception of Deborah immortal be keeping this new version alive?

The Deborah of my novel was created anew. From being a challenge – someone I found it difficult to get close to – I was suddenly sitting beside her, listening to her story, hearing her voice, telling her tales. The first draft of the novel was finished within months.

My Deborah Wybrow – the fictional creation – first appears in Attend sitting on a bench in Crossfield Street, Deptford, London SE8 – the very spot on which the real Deborah – the original 102-year-old woman who inspired my novel – died in 1835. And so a new life was born.

West Camel was born and bred in south London, and worked as an editor in higher education and business before turning his attention to the arts and publishing. He has worked as a book and arts journalist, and was editor at Dalkey Archive Press, where he edited the Best European Fiction 2015 anthology, before moving to new press Orenda Books just after its launch. He currently combines his work as editor at Orenda with writing and editing a wide range of material for various arts organisations, including editing The Riveter magazine for the European Literature Network. He has also written several short scripts, which have been produced in London’s fringe theatres, and was longlisted for the Old Vic’s 12 playwrights project. Attend is out now in paperback and eBook from Orenda.

West Camel was born and bred in south London, and worked as an editor in higher education and business before turning his attention to the arts and publishing. He has worked as a book and arts journalist, and was editor at Dalkey Archive Press, where he edited the Best European Fiction 2015 anthology, before moving to new press Orenda Books just after its launch. He currently combines his work as editor at Orenda with writing and editing a wide range of material for various arts organisations, including editing The Riveter magazine for the European Literature Network. He has also written several short scripts, which have been produced in London’s fringe theatres, and was longlisted for the Old Vic’s 12 playwrights project. Attend is out now in paperback and eBook from Orenda.

Read more

westcamel.net

@west_camel